Here is Giovini, who was a Protestant convert, and is noted as a very anticlerical (specifically anti-Catholic) writer:

This book includes an appendix of thirty pages of notes by Shadal, whom Bianchi-Giovini calls "mio amico." The author writes that most of the notes only correct small things, and some of the more major ones are just differences of opinion relating to their differing worldview. However, he says, this isn't the place for a controversy, where everyone ends up still thinking as they did before anyway, so he prints them so that the reader can read them and decide and form their own opinion. Nice!

On pp. 108 - 09 of his book there is the following paragraph:

A tradition has been preserved documenting the bloody tendencies of the time, when passions and prejudices reigned. Under Alessandra, her brother Giuda [sic] Ben Scetah and Giuda Ben Tabai ascended to power as Nasi and Patriarch of the Sanhedrin. In charge of that body, they allowed violence of all kinds, under the veil of religion and justice. Under the pretext of sorcery, Simone once arrested 80 women in Ashkelon, who fled to a cave, and he hanged them all in one day. To justify this atrocity, it was said that Simone was incited by a holy man who told him of his vision of Hell, where he saw the punishment for the Nasi of Sanhedrin if he did not exterminate the witches.

For his part, Giuda Ben Tabai cut of the head of a man accused of being a false witness, solely to refute the view of the Sadducees who did not subject a false witness to extreme punishment unless he had caused the death of the accused through false testimony. The public was very upset by this act, and word spread among the masses that you could hear groans every night at the tomb of the executed man. Simone Ben Scetah confronted his colleague, who it is said did penance, but Giuda did not fail to rebuke him too for being quick to shed blood. Each one complained to the other of cruelty, and both pretended to be more moderate and pious. It is said that Simone was so quick in judgment that the sentence was often not sufficiently established to prevent an unfortunate death. Because of the incident with the witches, his son was falsely accused in retaliation, and the council condemned him to death according to the code set by its Nasi. Realizing that he was at fault, [Simone] condemned the extreme sentence for the youth, and with the sorrow of a father, the execution would have proceeded if the false accusers had not admitted the truth.

In the table of contents, this section is called "Simon Ben Scetah e Giuda Ben Tabai, loro severita," "Shimon ben Shetach and Yehuda ben Tabbai, on Their Severity."

Shadal inserts a note for this section (pp. 606 - 08). Here is what he writes, quoting directly from the book, and commenting afterward:

Shadal inserts a note for this section (pp. 606 - 08). Here is what he writes, quoting directly from the book, and commenting afterward:

On pp. 108 - 9 - Giuda ben Tabbai and Simeone ben Sciatach (Note: I have preserved both of their Italian spellings of these two names, as I did in the text translated above) are gratuitously represented here as men who "allowed violence of all kinds under the veil of religion and justice." Jost, a sufficiently bold writer, paints a very different picture (III, 84 - 93). "Under the pretext of sorcery, Simone once arrested 80 women in Ashkelon, who fled to a cave, and he hanged them all in one day." Why on a pretext? What militates against a legal presumption in favor of the judge's sentence? Is it likely that a man (and note that this is not a celibate monk, but the father of a family) secretly harbored deadly hatred toward 80 women? But — it will be argued, the accusation is itself absurd — imaginary accusations of witchcraft is a crime no less than water poisoning, and the like, which in barbarous times served as a pretext for many, many atrocities.My answer: I do not know if witchcraft (its effects, apart from the causes to which they are attributed) is absolutely absurd (see Ennemoser "Geschichte der Magie," Leipzig 1844). Suppose it is. But the Mosaic Law expressly recommends (Exodus 22:17) to not allow a witch live. What could this judge do? He had left things alone for a long time, but when this scandal came out among the people who began to dream or say that he deserved Hell for his negligence, he could not help but to make legal inquiries into the matter, and he found that those women were practicing what was then called witchcraft and he could do nothing but condemn them to death. It happened then that his son was falsely accused of a capital offense and also sentenced to death. As the innocent young man was about to be executed, the accusers recanted. Simeone wanted to save his innocent son, but the son said: Father, if you want to do something positive for the public good, let me be like the threshold that is stepped on by everyone, without regard for me. Simeone let his son perish according to the law so that this terrible example would ensure respect for the law. It would frighten slanderers and also the wealthy, who would fear playing the courts if they would make them pay dearly for their retractions. (i.e., it shows that false testimony, where witnesses can't retract, is a grave matter. - S.)Moving on to Giuda ben Tabbai. The Sadducees claimed that false witnesses were not to suffer the penalty of death (to which the Mosaic Law already condemned them) unless the accused had already suffered that undeserved punishment. It happened that only one of the two witnesses in this case could be proved false. The testimony was therefore left ineffective, and the slandered one was acquitted. But the witness was not found less guilty [even though the other witness was not discredited]. Giuda ben Tabbai wanted to punish the false witness to give an example, so that all should realize that the law punishes false witnesses. Despite Giuda's good intention, Simeone reproved him rigorously, and reminded him that the traditional law acknowledged that the witnesses did not incur the death penalty for slander when both of them were not proven false. The book says: "something positive for the public good," etc. Why not report it as it says in the Talmud (the only source for these stories)? It says that Giuda was going to prostrate himself on the tomb of that witness asking forgiveness. A voice was heard. The people believed that it was the voice of the dead, and Giuda said: The voice, when I am dead, you will not hear it anymore. " (i.e., it was Giuda's own voice, lamenting his guilt.) But "Giuda did not fail to rebuke [Simone] too for being quick to shed blood," the Talmud does not say this.

His reference to Jost may be unclear. Jost was a very celebrated Jewish historian who wrote a multi-volume History of the Jews (and translated the Misnah into German, which is interesting because the Tiferes Yisrael sometimes cites him, unnamed of course). He was not exactly particularly sympathetic to the Talmudic rabbis and could hardly be called an apologist for the rabbis or Talmudic tradition. Zinberg writes of him "בכלל, די פירושים, ווי זייערע גייסטיקע יורשים - די רבנים פון די שפעטערע דורות, זיינען יאסטן ניט וויניקער פארהאסט ווי [דוד] פרידלענדען," "In general, he hated the Pharisees and their spiritual heirs, the rabbis of later generation, no less than [David] Friedlaender . . . " Even if Zinberg exaggerates, this is what Shadal meant by noting that Jost was a "bold" writer, and it is therefore worth citing him since his non-apologetic portrait of Shimon ben Shatach and Yehuda ben Tabbay portrait is softer. Shadal's personal relationship with Jost is interesting. This is not the place to explore it in full, but suffice it to note that when Shadal assumed his post as Professor at the Padua Rabbinical Seminary he was recommended Jost's volumes of history to use for teaching his students, and he was appalled by what he read. So he began to write his own teaching material.

A lot of the Shadal correspondence to Bianchi Giovini is printed in Epistolario, his collected Italian, French and Latin letters. On page 441 is a letter dated Dec. 18, 1844, apparently Shadal had not heard from him in a few weeks, so he writes: "Nel mentre che il di Lei silenzio mi faceva temere che le 80 streghe fatta avessero qualche malia a danno della nostra amicizia" "Your silence made me think that 80 witches and their witchcraft came between our friendship." He then goes on to discuss his son, whom he was very proud of, who was "conceived amid criticism and antiquities" and his work on the Ethiopian Jews.

Writing once more, Feb. 3, 1845, Shadal congratulates Bianchi Giovini for the immanent appearance in Italy, for the first time, of a volume on the history of the Jews written in a spirit of fairness and impartiality. He then returns to the Talmudic story discussed in in this post, writing that he simply can't resist returning to the 80 witches.

A lot of the Shadal correspondence to Bianchi Giovini is printed in Epistolario, his collected Italian, French and Latin letters. On page 441 is a letter dated Dec. 18, 1844, apparently Shadal had not heard from him in a few weeks, so he writes: "Nel mentre che il di Lei silenzio mi faceva temere che le 80 streghe fatta avessero qualche malia a danno della nostra amicizia" "Your silence made me think that 80 witches and their witchcraft came between our friendship." He then goes on to discuss his son, whom he was very proud of, who was "conceived amid criticism and antiquities" and his work on the Ethiopian Jews.

Writing once more, Feb. 3, 1845, Shadal congratulates Bianchi Giovini for the immanent appearance in Italy, for the first time, of a volume on the history of the Jews written in a spirit of fairness and impartiality. He then returns to the Talmudic story discussed in in this post, writing that he simply can't resist returning to the 80 witches.

Admittedly, he says, it is possible that some Pharisees took advantage of their favorable political moment to break down their opponents (though not with the same cruelty as the Sadducees dealt with their opponents). He says that it isn't impossible that some partisan female Sadducees were changed by legend into a coven of witches. But, we may ask, how could the Sadducees, who denied angels and demons as part of their doctrine, be susceptible to the charge of sorcery? Assuming than that the Pharisees had acted on a pretext to attack the Sadducees, something other than witchcraft would have been invented, for it is a crime which was incompatible with the principles of that sect. Why were women hiding together in a cave altogether? To practice their esoteric arts. Also, the fact that they lived in Ashkelon and not Jerusalem is significant, for they lived far away from the Court, and could hardly have aroused in the Pharisees a politically motivated hatred. As for the Pharisees, if following the law and putting criminals to death is cruel, then they are cruel and vindictive. If they do not pursue the law vigorously and make few executions, then they are the cause for the demoralization of the people through lawlessness.

Peace out,

SDL

Since Dr. Alan Brill recently posted about Chief Rabbi Hertz's treatment of "Haggadah" in his introduction the Soncino Talmud, which he calls "legend pure and simple." On pg. 313 of the Hertz Pentateuch there is nearly one-and-a-half columns about Witchcraft (Ex. 22:17 'Thou shalt not suffer a sorceress to live'). The comment

- denies there was any reality to witchcraft

- asserts that it negated the unity of God and was "an abominable form of idolatry"

- points out the Septuagint translated "mechashefa" as "poisoner"

- notes that some commentators understand it as a prohibition to allowing witches to thrive, rather than a command to put them to death

- denies that the medieval horrors associated with witch-hunts can be traced to this verse

- asserts that witchcraft, as a "sinister danger to Jewish social life" had ceased long before the 2nd Temple period

- affirms that "both-Jewish and non-Jewish scholars" have studied the Shimon ben Shetach episode and concluded that "it is merely Haggadic"

- that medieval Jewish sages denied the existence of witchcraft

- that torture to exact a confession was unknown and impossible in Jewish judicial procedure

- that Christianity casually disregards the Old Testament, even including portions of the Ten Commandments, and therefore its attitude toward any one thing cannot possibly be based entirely on a single verse in the Old Testament

- the New Testament is a demon-haunted book

- that is is estimated that in Germany alone 100,000 women and girls were killed for witchcraft over the ages

- that as late as 1709 a woman and her daughter were hung in Huntingdon for causing storms by witchcraft

Got that?

For further details on Jewish scholars who concluded that the Shimon ben Shatach story is historical, see the footnote on pg. 220 of Harvey Meirovich's A Vindication of Judaism the polemics of the Hertz Pentateuch.

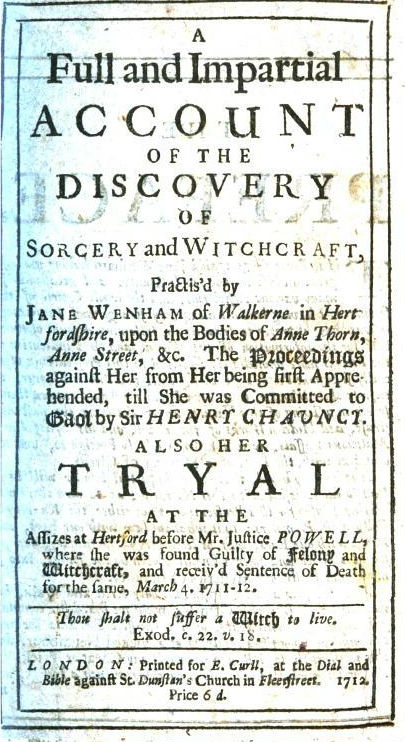

By the way, I am not certain, but I think that the Hertz Pentateuch is mistaken about Huntingdon in 1709. It seems to me that the said witches were hung in 1593. However, it is no joke that a woman named Jane Wenham ran into a whole lot of legal trouble in 1712. Her case aroused a great debate about whether witchcraft was real.

Finally, I include an 1883 representation of Jost's presentation of the Shimon ben Shatach/ Judah ben Tabbai story. I include it especially because of what is written at the end which shows how their story was definitely viewed in those times, an "illustration of the hatred of the two parties, both zealous for the written law, but sacrificing their own lives and those of others for their own interpretation of it. "

I have nothing to add, but I loved the post.

ReplyDelete