In the 19th century, one of the tasks Jewish writers in Eastern Europe set for themselves was to make contemporary literature available to Jews of Eastern Europe of varying education and intelligence, who did not know a European languages besides Yiddish. Therefore, many of them translated or adapted works of every sort. If it was intended for a popular audience, it would be translated into Yiddish. If intended for a more scholarly audience, such works were translated into Hebrew. Perhaps the most prolific of these writer-translators was Kalman Schulman (1819-1899) . The Jewish Encyclopedia evaluates his style as follows: "Schulman, in his writings, limited himself to the use of strictly Biblical terms, but so expert was he in the use of Hebrew that there was hardly any shade of thought or any modern idea that he could not easily express in that language. The result was that he came to be the most widely read Jewish author. "

Although a

maskil, he was of the moderate type and knew how to write in such a way that his books were widely read and tolerated in the traditionalist camp (note that he is referred to as "[the] writer[s] R' Kalman Shulman of Vilna" without further qualification in

Making of a Godol pg. 643). One of the works he produced was a Hebrew translation of several volumes of Graetz's history of the Jews, the

Geschichte der Juden. As anyone who has read this work knows, even in English, Graetz could write in a very provocative way which is often quite offensive to traditional sensibilities. For him the only sacred cows were the cows which he personally felt were sacred. Thus it is not surprising that Schulmann's decision to translate the

Geschichte into Hebrew (with Graetz's permission) was not appreciated by everyone. Furthermore, it is no surprise that Schulmann would be self-conscious regarding such criticism. He knew what kind of reputation he had cultivated, and hardly wanted to alienate a large part of the public whom he hoped to reach. Thus he never intended to faithfully translate Graetz, and nor did he. Rather, he put Graetz into acceptable garb.

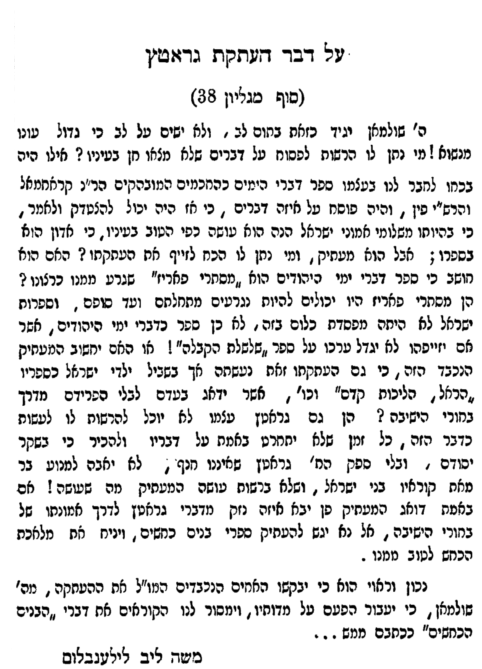

There were some interesting exchanges concerning his decision and the manner in which he made the translation in the pages of the Hebrew periodical

Hazefirah in 1876-77. Below is a letter from Schulmann to an unnamed rabbi, who evidently had been displeased to learn that he had been translating Graetz. Schulmann responded that he would never produce a gentile book [i.e., a modern critical work of history) in the Holy Language, and the rabbi ought to realize that his translation is written with faith, and he omits all the things written with a critical spirit. Furthermore, Graetz isn't a Reformer. On the contrary, he is a major opponent of Reform Judaism.

While this may have mollified this particular critic, it appalled one on the left. Moshe Leib Lilienblum was horrified at this candid admission that he was rewriting Graetz in

frum fashion. Schulman admits that this is what he is doing, but doesn't realize that how bad it is. Who gave him the right to put words into an author's mouth? If he had the ability to write an original work of history like Rabbi Nachman Krochmal or Rabbi S. J. Fuenn, then of course it's his business how he writes it, and he could decide to write it in a pious way so as not to shake the faith of the pious reader. His book, his rules. But as a translator, who gave him the right to essentially create a forged text? Does he think Graetz's

Geschichte is like a cheap novel?* Was Schulmann's intention to prepare this translation along the lines of previous popular histories of his, which he wrote for children and

yeshiva bachurim? Frankly, opined Lilienblum, Graetz shouldn't allow it. If Schulmann was absolutely adamant that he could only produce a work which wouldn't offend the sensibilities of

yeshiva students, then let someone else translate it. Ouch.

Some time later Nachum Sokolow rose to defend Shulman. His view was that it is okay for a translator to change an original work. He justifies it on the following basis: a work of history produced by a historian contains two parts. 1) The facts, and 2) the views and interpretations of the historian. Ideally the historian would only give the facts. But this isn't really possible, so he injects himself into the work and that's why works of history always contain the views of the historian. Given this, the only thing which is of crucial importance is that the facts aren't changed. So long as Schulmann doesn't change the facts, what difference does it make if he replaces Graetz's biases with his own? In fact Graetz, undoubtedly a talented and great historian, had a major weakness himself, namely his biases. So not only is there no harm in Shulman trimming some of that out, it actually enhances the text by making it less biased.

* "A cheap novel" - That's how I chose to translate

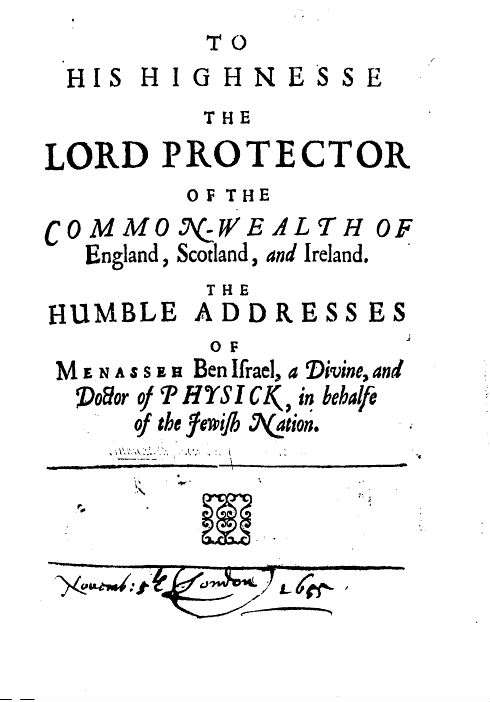

מסתרי פאריז, which is the name of Shulman's translation of Eugene Sue's

Les Mystères de Paris.

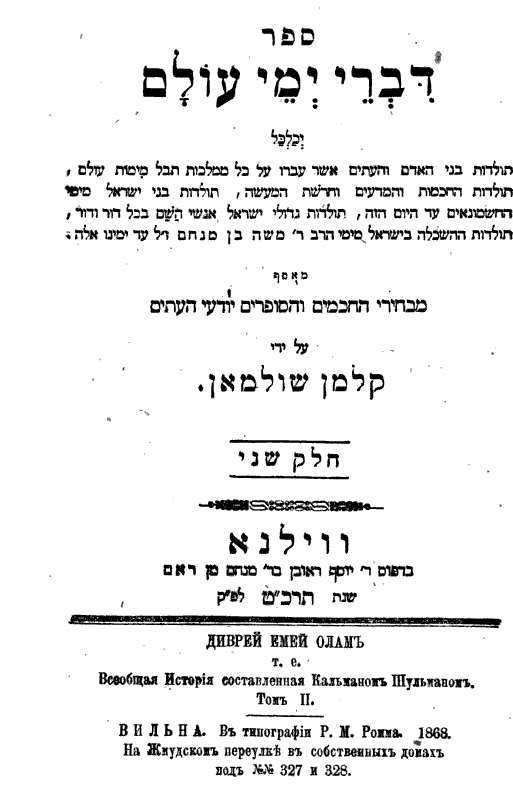

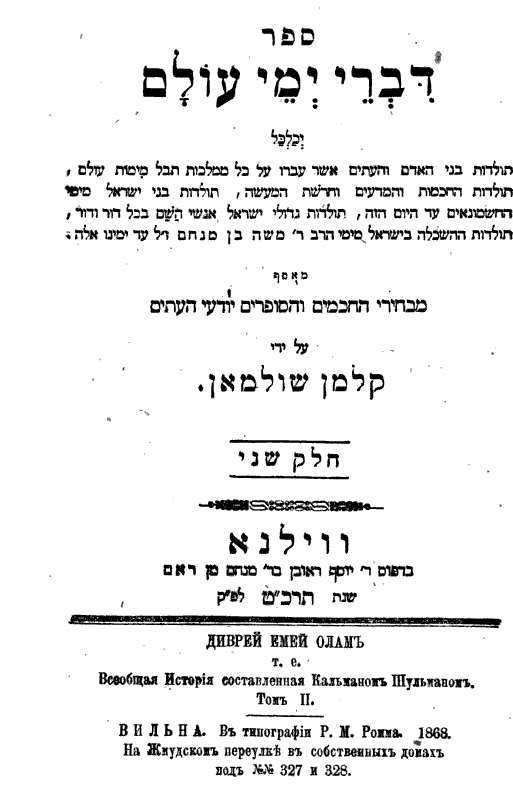

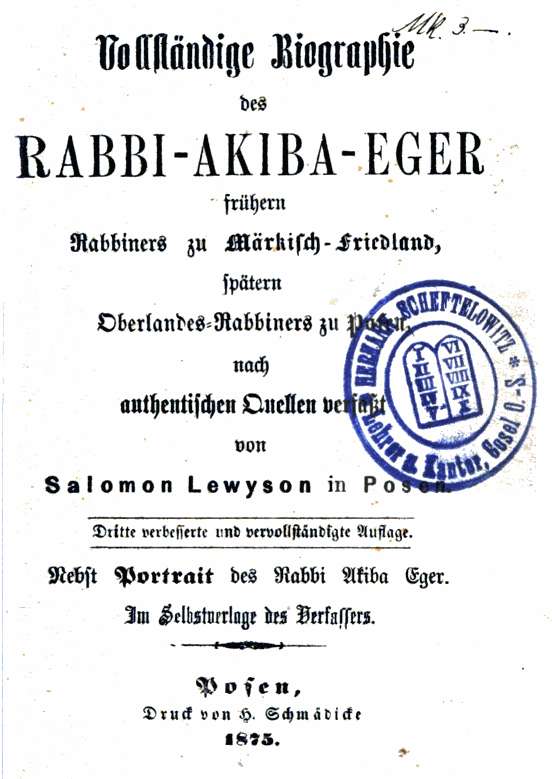

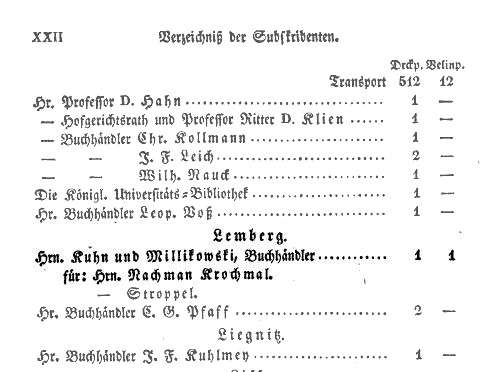

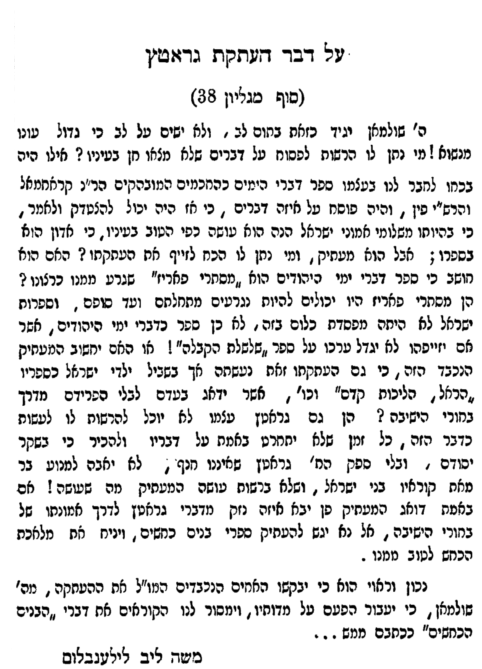

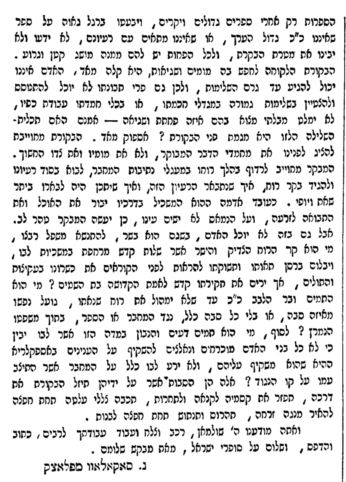

The title page of the second volume of the work in question: