Holy Hyrax called my attention to the 5th annual

Ariel Avrech z"l Yahrzeit Lecture at the

Young Israel of Century City (

listen).

The lecturer was Gil S. Perl; the topic "What Was the Rosh Yeshiva Reading? Intellectual Openness in 19th Century Lithuania?" Drawn from his research for his dissertation on the Neziv (see my prior post

On the alleged average intelligence of the Neziv), a couple of points he raised are worth mentioning (although this should not absolve you of listening to the very interesting talk - but if you don't want to, here is a summary of the lecture topic:

link).

The first point (discussed in his dissertation on pp. 345-46) concerns the great depth and breadth of Hebrew grammatical knowledge in possession of the Neziv. The memoir by his nephew R. Baruch Epstein contains the following story:

The

maskil Joshua Steinberg asked the Neziv how it was that he was had become so adept at grammar, Bible and cognate studies, when clearly he was a traditional talmid chochom who occupied his time entirely with Talmud and rabbinic literature? Furthermore, he - Steinberg - achieved his expertise in these subjects only after many years of hard toil in these subjects.

The Neziv, says Epstein, replied with a parable of two linen merchants. One has a huge business, the other barely anything. Noticing that the bales of linen in the stock of the larger merchant are bound by fine straps that are worth something in and of themselves, the lesser merchant asks the other where he gets those straps. He is told that he gets them from his supplier. Thinking of an opportunity the small merchant tries to get many straps from the supplier, who charges for them in accordance with what they're worth. The merchant doesn't understand; why are they thrown in for free for the larger merchant? He is told that they are free if you buy a great amount of linen, but not if you only came for the straps.

Is the message of the parable not clear?

(It does not need to take up four pages, as it does in the memoir. Therefore I put them in a pdf, which you can read if you like:

link)

Now, it is not possible to know if this exchange took place or not, or if it did exactly as recounted, but the implication is certainly that the Neziv kind of acquired this great knowledge by osmosis, and with divine help. It certainly does not imply that he learned grammar by reading books on grammar, for example, or at least it skirts the issue.

Yet Perl notes that the Neziv quotes such works in his early work on the Sifre (which was published under the title

עמק הנצי"ב fifty years after his death). For example, see the following (Shoftim, vol. iii, pg 189):

As you can see, he directs the reader to the introduction of the grammatical work

אשכול הכופר by the Karaite scholar Yehuda Ha-dassi, which obviously was on his reading list. The commentary contains references to other works, like Levita's Massores Ha-massores, so it's obvious that the Neziv was familiar with high level standard grammatical and massoretic works.

It should be noted that even though the Neziv's knowledge is therefore no mystery, that doesn't mean that the exchange never took place - only that the significance of it is not as it appears. This is similar to a popular belief that the Chazon Ish was very knowledgeable about medical topics, without having perused medical literature. In fact, it appears that he was very knowledgeable about medical topics, and he

had perused medical literature.

The second interesting point concerns the very same passage (this is discussed on pp. 56-58 of the dissertation).

As you can see, another source is the introduction of

חומש באסו ות"א. This looks like a chumash with Targum Onkelos, but the title or publication place of the chumash is unclear.

באסו? Besso? Bessau?

Of course readers of this blog already understand that its an error and should read

דאסו, Dessau, and that means that

ת"א stands for Targum Ashkenaz, with German translation. This means that the reference is to the introduction of Mendelssohn's edition of the chumash, the

אור לנתיבה. As there seems to be no

באסו chumash in existence, and as Perl looked up the reference and found it in the

אור לנתיבה, it seems beyond doubt that this is what was meant. The only question is whether it was an honest error (for example, the

ב looked like a

ד in the manuscript or just a simple typo) or a willful one.

Perhaps the latter is less likely, because removing the reference would have accomplished the same purpose without possibility of discovery (the manuscript is in possession of descendants of the Neziv). However, Perl found that when he wished to see the manuscript he was allowed by them to do so, but under difficult conditions.* First, he was seated in between two people. Second, he was not allowed to actually look at it freely. He had to tell them what he wanted to see, then they looked at it and decided if he could see it, sometimes letting him, sometimes not letting him. Perl realized what was going on, so he began to ask to see passages a little before the ones he was interested in, hoping that what he was interested in would be on the same page. In this particular case, he only got a quick glance at the reference and he couldn't see if it was written with a

ד or a

ב, or a

ד that looked like a

ב. But he did see that it was underlined in pink pencil, which suggests at least that this passage was noted by someone, perhaps the publisher of the work, and perhaps it was a willful distortion of the text.

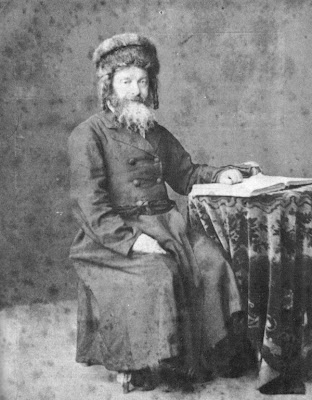

Paranthetical side point: can you imagine today's gedolei yisrael posing for a studio portrait with an open sefer sitting on a table next to them? Times (and conventions) do, indeed, change.

*

Of course, it was nice of them to give him the time of day at all, especially considering the fact of their own religious sensibilities and that his research was for a university doctorate.