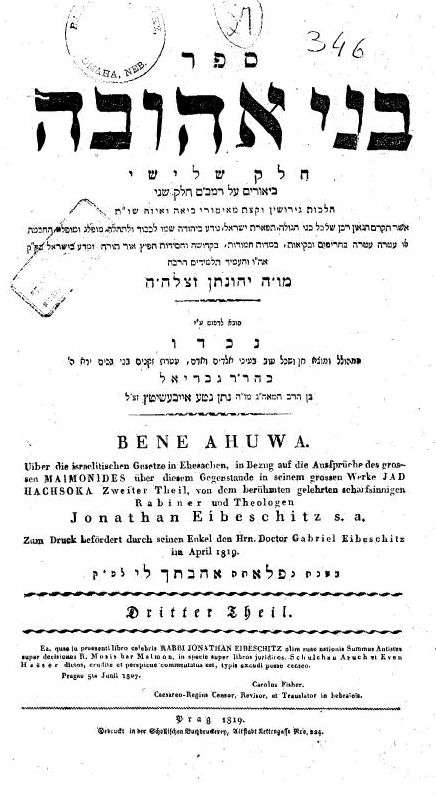

Here is the title page to one of the volumes of בני אהובה, the 1819 publication of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschutz's comments on the Rambam and SA Even Ha-ezer. As you can see, it was published in Prague by Doctor Gabriel Eibeschitz the "enkel" of Rabbiner und Theologen Jonathan Eibeschitz (it also includes notes by Rabbi Uri of Dresden, Dr. Gabriel's home town).

Doubtlessly you are wondering about Dr. Gabriel Eybeschutz. He was indeed a physician, and lived from about 1757 to 1849. According to one biographer he looked exactly like his grandfather, only without a beard, which may sound ad-hoc, but the same biography doesn't claim this about his other descendants, all of whom are noted. Incidentally, outside of the 'bad seed' line of R. Yonasan, namely his son Wolf and his progeny, only Dr. Gabriel was suspected of being a secret Sabbatian (grudgingly admitted by Mortimer Cohen, psycho-biographer of R. Jacob Emden). The story is that Dr. Gabriel was said to be Sabbatian, going to their meetings, and an acquaintance confronted him, telling him "You're so smart, what do you see in this nonsense?" He replied that he knows it's nonsense and he tells it to his Sabbatian acquaintances. Make what you will of that.

"Incidentally, outside of the 'bad seed' line of R. Yonasan, namely his son Wolf and his progeny, only Dr. Gabriel was suspected of being a secret Sabbatian"

ReplyDeleteI'm almost certain this is not true. There should be a pg. in Ivah Lamoshav discussing suspicions against his other kids.

I was inexact, I meant his grandchildren (and I was probably unconsciously influenced by Mortimer Cohen's language).

ReplyDeleteIn any case, if it is strange that a R. Yonasan should be a ga'on and a ba'al halacha and a Sabbatian, it seems also strange and maybe stranger that Dr. Gabriel should involve himself in publishing halachic works if he himself was a Sabbatian (and obviously much more modern and secular than his grandfather).

Indeed, my "papa" called me this, and introduced me this way to his associates at shul. He spoke english flawlessly and without a yiddish accent, and his speech carried only a few interspersed words. Einekel was one of them.

ReplyDeleteI'm 55 now, he's been gone for about 25 years, and I still miss him. Thanks for giving me a reminder of his memory that has long been buried.

One of my rebbeim at YU, having just discovered what he considered to be an important fact about my ancestry, suddenly accosted me as I was waiting for the elevator and exclaimed, with an ear-to-ear grin, "Klein! You're Dr. Isaacs' einikel!" I had never heard the word before, but as startled as I was, it did not take me more than a second to figure out what he meant. For me, hearing the word "einikel" always triggers this oddly fond memory.

ReplyDeletePerhaps he was like a proto-Scholem: Fascinated in an academic sense by what he considered to be nonsense.

ReplyDeletescholem did not consider his area of study "nonsense."

ReplyDelete>scholem did not consider his area of study "nonsense."

ReplyDeleteCorrect.

Be that as it may, I find the story very odd - assuming of course that all the elements are true (the rumor, the question, the answer).

There are in yiddish two levels of diminutive : -l and -ele.

ReplyDeleteyung/yingl/yingele

moyd/meydl/meydele

hoyz/hayzl/hayzele

Not all the words in -l are diminutives e.g. "shlisl" key

Schlüssel means "key" in German. Same with "enkel," it sounds diminutive because of the -l, but it's really just the German word.

ReplyDeleteIt soundsd diminutive is some German dialects as well.

ReplyDeleteIn Hochdeutch little key would be:

Schlüsselchen

In Bavarian German, for example, you would be more likely to use Mädl than Mädchen for little girl.

>Hochdeutch

ReplyDeleteOf course, this should be Hochdeutsch