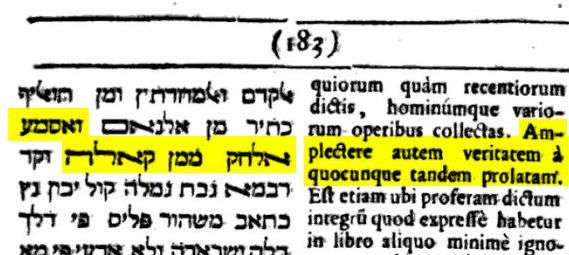

Parts of his monumental Mishnah commentary were published in 1655 in the original Judeo-Arabic, with a Latin translation, by Edward Pococke in his Porta Mosis (also given the Arabic title באב מוסי, or "Bab Mosi," which is cognate with the familiar Aramaic term בבא, which also means portal).

Here is how it appears:

Ibn Tibbon's famous Hebrew translation of ואסמע אלחק ממן קאלה is ושמע האמת ממי שאמרו. Far be it from me to play Rambam exegete, but it occurs to me that Ibn Tibbon was very smart to translate סמע literally to its Hebrew cognate שמע, which usually means to hear. While it could mean "accept" (indeed, R. Kapach [sic] changed Ibn Tibbon's שמע, hear, to קבל, accept) I'm not sure that was the Rambam's intention. After all, the huge problem everyone encounters is that what is true is not always apparent or can't be tested. What does it mean to accept the truth when so many issues are inexact, to say the least? If he meant "hear the truth," it becomes much easier to understand. Maybe you're in a position to accept it, maybe not. Maybe the position is true, maybe not. But at least listen. (The preceding was homiletical, and almost certainly not what he meant. Still, food for thought.)

As for the language, a long time ago Judeo-Arabic was discussed in the comments to one of my posts, and the question of why the Jews in Spain preferred to write some of their highest level religious texts in Arabic, from responsa to investigations into Hebrew language and grammar to commentaries like these (according to medieval sources the entire Talmud was even translated to Arabic, although I doubt it), while almost every other Jewish society right up to the modern period and even to the present, they always used Hebrew for their most serious and authoritative texts. In addition, the Judeo-Arab texts use loads of very Islamic terminology as exact equivalents of Jewish terms. 'Halacha' is 'alsharia' and 'teshuva' is 'fatwa,' and so forth.

I posited that the chief difference was Arabic itself, which had two qualities that other Jewish vernaculars did not have. First, it was similar to Aramaic (and Hebrew), underscoring the fact that the Talmud and Targums were written in vernacular language. Second, the phenomenon of diglossia (one language for scholarship and one for speech) was far, far more marked in Christian society. Arabic was both the classical language of prestige and the vernacular.

In fact, as European vernaculars rose in prestige, with scholars creating lexicons and investigating their own spoken tongue, scholarship too began to be written in those languages, and the Jews in Europe too began writing scholarship in the vernacular they considered prestigious (i.e., correct Italian, German and French). Writing the vernacular in the Hebrew alphabet ultimately fell out of fashion due to other considerations, such as the widespread ability to read and write the Latin alphabet. Perhaps another difference is that the Jews perceived Islam very differently from how Jews perceived Christianity. Many parallels, from ablutions, to fixed times for prayer, to beards, to circumcision, to fasts, to nidda, to halacha/ sharia, to a body of oral teachings, etc. made "sharia" seem a lot more like "halacha" and rabbis like 'ulema' than anything found in Christendom, where these religious similarities were not only missing, but many more differences could be found. In those lands the Christians didn't esteem their own spoken language, and neither did the Jews.

Far be it from me to play Rambam exegete, but it occurs to me that Ibn Tibbon was very smart to translate סמע literally to its Hebrew cognate שמע, which usually means to hear.

ReplyDeleteSama is a much broader term in the Arabic. It means accept, tradition, and to experience.

Collections of Aristotle or Ibn Rushd are called "Kitab al Sama" or "Sama al (fill in subject)" meaning "The tradition on this topic."

It is used in Al-Ghazzali, another source of Maimonides, as to hear the word of God including prayer, prophecy, and music.

Thanks. I did look it up in a few dictionaries. We may as well note that "al-haq" is one of the 99 names of God, and also denotes more than truth. Like I said, I was making a derasha.

ReplyDeleteI have a taiva to be able to read the Pirush Hamishnayes in the original. I have been unable to find anything addressing classic Arabic which does not involve extensive readings of the Koran. If you or any readers of the blog could suggest something I would greatly appreciate it.

ReplyDeleteThanks

Midwest

How does Judeo-Arabic notated in Hebrew letters handle all the unusual consonants that are found in Arabic (but not Hebrew)?

ReplyDeleteImperfectly, like all languages that use the wrong alphabet. It uses diacritics.

ReplyDeleteMidwest, I'll offer some suggestions later. (Squirming toddler on my lap.)

Arabic was both the classical language of prestige and the vernacular.

ReplyDeleteNo, it wasn't. And isn't. The "Arabic" dialects are as far from Written Classical Arabic (in which the Rambam etc. wrote) as modern Italian is from Latin. Some of them are even farther. And in Spain, it's not even clear that people spoke a Semitic language at home, rather than a Romance one. (Note that some of Yehuda Ha-levi's poems have the last lines of stanzas in a medieval Romance dialect, and are some of our best evidence for this dialect.)

The Professor who taught me Arabic has told me a story about being in a Lebanese restaurant in New York, and speaking with the proprietor (in English or French, presumably), who told him that (a) he [the proprietor] couldn't speak Syriac, and (b) he barely knew Arabic. What language did he speak, then? Libanii -- "Lebanese".

ReplyDelete*Libnaanii, that is.

ReplyDeleteFirst, it was similar to Aramaic (and Hebrew), underscoring the fact that the Talmud and Targums were written in vernacular language.

ReplyDeleteEfsher. One might also argue that it was because the Jews of Spain were more integrated into the general society.

Anyway, they didn't invent the idea of writing Torah in Arabic. The Geonim had already been completely bi-lingual writers, in Aramaic and Arabic. Spanish Jewry adopted from them the practice of writing in Arabic, but dropped the Aramaic.

Midwest

ReplyDelete>I have a taiva to be able to read the Pirush Hamishnayes in the original. I have been unable to find anything addressing classic Arabic which does not involve extensive readings of the Koran. If you or any readers of the blog could suggest something I would greatly appreciate it.

My suggestion is to sit down with a bilingual edition and pretend you're being ma'avir sidra.

S

ReplyDeleteOddly enough I never thought of that. It seems like it might be an idea. Could you let me know where I could find such a item. Thaks

Midwest

ANON:

ReplyDelete"Could you let me know where I could find such a item"

i've seen bilingual judeo-arabic/hebrew editions some of rambam's work (by r. kapah), but i don't recall what

and you can easily get bilingual editions of saadia gaon's emunot ve-de'ot and tafsir

S:

you have to do more than pretend. many of us

pretend to be maavir sedra with onkelos, yet learn little aramaic. and speaking of aramaic . . .

"they always used Hebrew for their most serious and authoritative texts"

gemara, certain midrashim, daniel?

>you have to do more than pretend. many of us

ReplyDeletepretend to be maavir sedra with onkelos, yet learn little aramaic. and speaking of aramaic . . .

Yes, but Midwest expressed his commitment. Many are ma'avir sidra and pick it up. The reason I recommended this is because it is kind of my preferred way of doing things. I know that you can spend many months plodding through grammars and so forth, but I find that I prefer the rewards that come with jumping right in. The advantage here is that he doesn't have to learn to read Arabic in its alphabet which is very, very hard (at least for me) and ultimately irrelevent for Judeo-Arabic since it's written in Hebrew letters anyway. Secondly, he will learn a great deal about the cognates, and which consonants shift, if he reads it together, especially the Ibn Tibbon version. Thirdly, he doesn't have to learn Arabic through the Koran, as per his wishes.

Gorfinkle's Shemoneh Perakim is online, and it includes both the Arabic and Hebrew text in parallel columns.

http://books.google.com/books?id=CLcFAAAAYAAJ&pg

Porta Mosis has much of the Kitab as-Siraj (Pirush ha-Mishnayos), but only has the Arabic

http://books.google.com/books?id=sJwUAAAAQAAJ

Still, he can print some of these out, and in the case of Gorfinkle even order a print on demand one for $8 here

http://my.qoop.com/google/CLcFAAAAYAAJ/

there are several other sources, probably on Hebrewbooks (and you can usually order a pod version from there), and I know the complete Yemenite chumash with Tafsir is available in pdf online somewhere (I am handicapped at the moment due to some unfortunate computer trouble, but in a few days he or anyone can email me and I can give proper links and/ or send pdfs).

>gemara, certain midrashim, daniel?

Obviously I meant post-Talmudic, but even so, Aramaic was seen as having some sanctity like Hebrew when it was not the vernacular. On the other hand you could simply argue, as someone did above, that the Babylonian and Spanish Jews simply continued the Amoraic and Geonic tradition, which was to use the vernacular (Aramaic and eventually Arabic).

Thanks to all. hebrewbooks.org is unbelievable

ReplyDeleteMidwest

i just reread simon federbush's article on rambam's attitude to hebrew vs. arabic.

ReplyDelete1) arabic is hebrew in a corrupted form

2) rambam wrote mostly in arabic because of et la'asot, and this is when jews resorted to writing in the vernacular (this i didn't understand, as it certainly doesn't apply to ashkenaz, maybe he was referring to sefaradim?)

3) he brings some interesting sources to illsutrate how highly rambam thought of hebrew. and he later regretted having written in arabic. he longed for these works to be translated into hebrew and he opposed those who wanted an arabic translation of the mishneh torah.

"Many are ma'avir sidra and pick it up. "

for a lot of people it is a rote and rapid ritual that they perform without a thought (not that there is anything wrong with this). i think you do have to have some minimal kavanah to pick up some of the language.

"this is because it is kind of my preferred way of doing things. "

yes, immersion is always best. although my preferred medium for foreign language immersion is the television :)

I am mavreh sedra with English and find it ten times more meaningful than doing it with Onkelos. I actually think I am mekayem the original halacha. I have no idea what the point of reading Onkelos is if one understands neither the Hebrew or Aramaic.

ReplyDeletePlease explain to us laymen why you see Arabic language as a great danger to emunah, as you have stressed this point in other blogs without elaborating on it.

ReplyDeleteStudent V,

ReplyDeleteI didn't say or mean that Arabic is an emunah challenge. A historical, linguistic based approach to the study of language, which in the case of Hebrew also means the study of its cognate languages, including Arabic, calls into doubt many traditional assumptions, such as the priority of the Hebrew language, the uniqueness of Torah literature and concepts, and it may lead to doubts or questions about traditional Talmudic or halachic interpretions or rules.

Chaim, you are talking about comprehending the sidra. Abba and I are talking about that, and also comprehending Onkelos and his Aramaic language. You're right, to rattle it off is pointless. But there is a great advantage to learning the language; think of how often Rashi cites Onkelos to clarify the meaning of the Hebrew text.

Again, I don't doubt that many or most have no intention of understanding Onkelos and don't pick up Aramaic, but many do. The first step is motivation. If you want to do it, then you're being ma'avir sidra is going to be very different from how it is when you're just trying to get it over with. Indeed, if you feel Onkelos is only worth it to tell you what the Hebrew means, and you can accomplish that with an English translation, go right ahead. I'm not sure that's halachically sound advice, but some posekim are of the view that you can read it with Rashi instead of Onkelos, so I can't see why English would be worse.

After all, the huge problem everyone encounters is that what is true is not always apparent or can't be tested. What does it mean to accept the truth when so many issues are inexact, to say the least?

ReplyDeleteIndeed, Rambam himself is quite concerned with this. See Rambam Hilchos A"Z 2:4-6

http://www.mechon-mamre.org/i/1402.htm

Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteI understand your taivah to learn Comm. to the Mishnah in the original. You might want to try the series from Maaliyot (Yeshivat Bircat Moshe in Maaleh Adumim). The Rambam's peirush is presented side-by-side with considerable explanations of Arabic terms and how the Rambam uses the same term throughout his writings as well as standard iyunim. I have it on Berachos, Peah, Shabbos, and Avoda Zara, and I think they are working on more. Definitely more user-friendly than the Google Books/Hebrew Books links (not that I'm denying the general awesomeness of GB/HB) Here is the link to one of them:

http://www.ybm.org.il/hebrew/Product.aspx?Product=40&Category=24

S.,

ReplyDelete1) I was talking about the halacha and the very basis for the halacha. The Shulchan Aruch Harav explicitly allows one to use a vernacular translation. In my opinion, it is the only way to be truly mekayem the halacha if one does not understand Onkelos.

2) Trying to learn Aramaic is different, and I agree with you that being mavre sedra using Onkelos would help one in this regard (assuming one knows the meaning of the Herbrew that one is translating!).

Eric

ReplyDeleteThank you very much.

One interesting item - using google teranslate I got

Mask Wig with Maimonides

for

מסכת פאה עם פירוש הרמב"ם

Midwest

To the commenter who wrote about funny consonants in Arabic but not Hebrew -- there are only two. The Daad, which is an emphatic D (distinct from Daal, which is daleth), and the Dhaa', which is an emphatic voiced dental fricative (th as in the word "the", but emphatic so the throat gets involved). No other consonant is an issue at all, as you can use the same Hebrew diacritics we all do. a gimal without a dot, for example, makes the same sound as ghayn (though judeo-arabic often instead just puts a diacritic over an `ayin for this). a daleth without daghesh is supposed to be fricative and certainly was for andalusian Jewry, so there is no need for diacritics to transliterate the letter dhaal. Heth is equal to the guttural arabic Haa', whereas a kaph without daghesh is equal to the Arabic khaa'. the letter thaa in Arabic can be written with a Taw without daghesh, which is how it would have been pronounced in Andalusia or Egypt where Rambam was writing.

ReplyDeleteThe pharyngealized qaaf of Arabic is exactly how Arabic-speaking Jews pronounce qoph, which is distinct from the letter kaaf in both languages (and you can hear this from any traditional Levantine or Iraqi Jew, as wel as the group of Yemenite Jews that doesn't pronounce this letter as a G).

Teth and the emphatic Taa' are the same letter. So are Saadi and the emphatic Saad (distinct from the letter seen, which is pronounced like our seen or as we pronounce our samekh, the difference having long been eroded for all Jews).

Judeo-Arabic does often, just to be extra clear, simply use a diacritical mark of one sort to indicate plosives (the daghesh of Hebrew), and a little dash on top to mark fricatives.

With regard to the only two consonants which are different -- Dhaa' and Daad -- these are written in Arabic by writing the letters Taa' and Saad with a dot on top. So Judeo-Arabic usually does the same, putting a dot on top of a Teth or a Saadi. Not all Judeo-Arabic has the same transliteration scheme though, that should be born in mind. I have seen some texts that transliterate a ghayn as `ayin with a dot on it (as Arabic does), and some that transliterate it as a fricative gimmal, that is, gimmal raphuy or gimmal without a daghesh (and that is indeed how Levantine Jews pronounce this phoneme).

to the blogger (wonderful blog btw):

r. qafih's translation seems more accurate to me, by the way. I don't see how your midrash on rambam is support for ibn tibbon's version. rambam meant what he said and said what he meant, which is to accept truth from whomever it comes from. Obviously this entails evaluating what is or isn't true. I don't see what the translation of r. qafih is lacking.

Well, first of all, אין משיבין על הדרוש.

ReplyDeleteThat said, I realize that the Rambam meant what he said and doubtlessly had the idea that you can know the truth by thinking very hard about things, but I am not so certain. Since you can't really always know what is true, contra Rambam, what you can do is always be willing to hear.