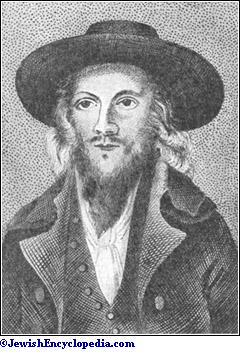

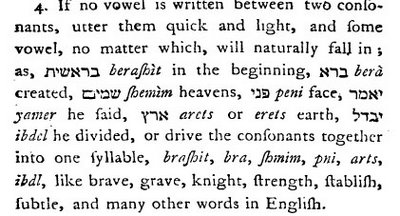

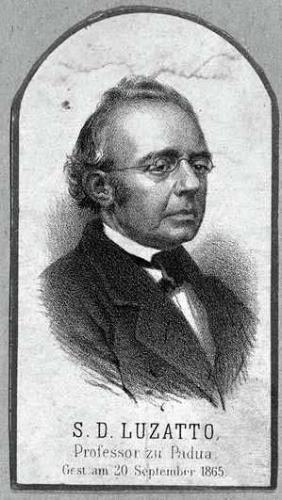

Shadal--R. Samuele Davide Luzzatto--was a great-nephew of another Luzzatto--Ramchal, author of Messilat Yesharim. He was an iconoclast in the sense that he was totally unafraid to be an original thinker. Given the intellectual climate some of us are familiar with today, some of the things he wrote seem shocking. But there is no evidence that he had a rebellious bone in his body. Eearly-mid 19th century Italy was not early-21st century Brooklyn. He wrote, for example, "I esteem Maimonides very greatly, but Moses the Lawgiver never dreamed of philosophy and the dreams of Aristotle." (

Letters no. 83, quoted in J. Enc.) True, the Vilna Gaon held a similar view about the Rambam, but today many people would say "[the Vilna Gaon] could say it," but certainly not Shadal (who?)!

Unlike his uncle, who was a kabbalist, Shadal was very skeptical of kabbalah in general, something he arrived at an early age--before his bar mitzvah. In 1814 his mother took ill and his father, who was very much into kabbalah, wanted him to pray certain kabbalistic tefillos (or perhaps pray with kabbalistic kavanot) for his mother. His father believed that his tefillos had a certain purity due to his age. Young Shmuel David refused, because he did not accept kabbalah!

This certainly would seem to be cruel, but at the time he was personally taking care of her, cleaning the house etc. And it is said that when his poor mother would cough up blood he was the only one in the family who could stand to be there to clean her up.

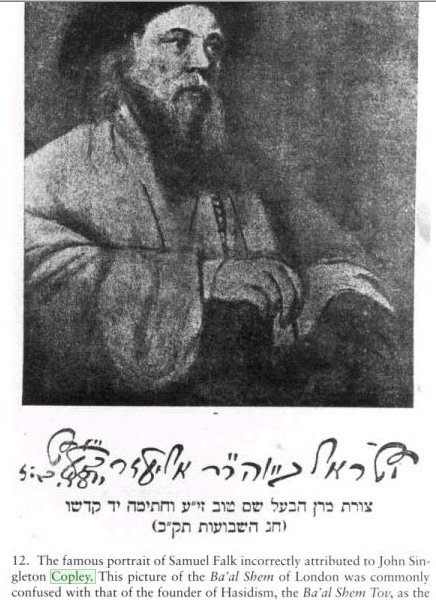

Anyway, this gets to the matter of kabbalah. To many people kabbalah is the holiest of holy. To say that it is authentic would be an understatement. But alas, not everyone shares this view. Others are totally antagonistic toward kabbalah. Some think it is pure bunk. Some think it is a type of philosophical search, perhaps analagous to alchemy as a proto-scientific field. In that sense, it isn't "true" but neither is it false and forgery.

Precisely where I personally fall isn't important, but let's say simply that I am not kabbalistically inclined. The thing about that is that so MUCH halakhic praxis derives from the kabbalah! Today is Rosh Hodesh. Removing the tefillin before mussaf is a kabbalistic practice. Reciting the ana bekoach prayer, the berich shemei are kabbalistic. Friday night kabbalat shabbat is kabbalistic. And on and on it goes.

The question is, if [I] lean away from kabbalah, should I follow kabbalistic practices?

The answer for me is

yes. Putting aside the fact that there is plain beauty in a lot of kabbalistic ideas and practices, which would seem to justify them in their own right, I coulnd't stop these things personally not because I "believe" in kabbalah, but also because it is close to impossible to perform kabbalah-removal surgery on halakhic praxis because it is so infused with kabbalah! In addition, I personally feel that to tamper with nussach and halakhah while I am still far from learned enough or perfect enough would be the height of yohora (religious haughtiness) for me. When it comes to things that aren't minhag avoseinu, e.g., inserting a passuk relating to my name at the end of shemona esrei (as per Shnei Luchot Ha-brit), I don't feel compelled to adopt it. But if we're talking about something like kabbalas shabbos or saying brich shemei, I'm not going to take out a scalpel!

Of course I've delicately avoided more touchy kabbalistic issues, such as saying a "le-shem yichud," before performing a mitzvah. Most of the practices I cited aren't really anything one way or the other. But when it comes to intending to perform a mitzvah "in the name of the unity" of God (last I checked, there was no problem with God's unity) or not wearing tefillin on chol ha-moed, a real halakhic issue, I have but to refer to the principle I outlined before: if my family does it, so will I.