I guess what I am trying to say is that the confusion, rather than fusion, of peshat and derash goes against my sensibilities.

Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Vertlach; a rant.

I guess what I am trying to say is that the confusion, rather than fusion, of peshat and derash goes against my sensibilities.

Battling reformers.

The thurst of his argument is that basically everything that is going on in Orthodoxy right now is rooted in the rise of Reform two-hundred years ago.

Most ominously, he writes

The problem, it seems, is that the chareidi community is still fighting the old battle. And, the new reform are.... the modern orthodox. Recall that the first debates between reform and orthodoxy were halachic in nature.Could it be?

The dilemma of the Orthoprax

Changes [in halakhah] did take place, but they were not done consciously. The scholars who legalized them did not perceive themselves as innovators. the changes were integrated into community life long before they sought - and received - legal sanction. They originally came about imperceptibly, unnoticed, the result of a gradual evolutionary process. By the time they demanded legal justification, they were ripe, overgrown, as it were. So much so, that in many an instance, whoever opposed the changes was considered a breaker of tradition, adopting a "holier than thou" attitude.

A Jew knows no other way of reaching out to God other than through halakha....

I hope you will understand why I cannot participate in the vote on women's ordination.... I am committed to Jewish tradition in all of its various aspects. I cannot, therefore, participate in a debate on a religious issue of major historical signifigance where the traditional decision-making process is not sufficiently honored; its specific instructions as to who is qualified to pass judgement not sufficiently reckoned with. Even to strenghten tradition, one must proceed traditionally. Otherwise it is a mitzvah haba'ah ba'aveirah.

It is my personal tragedy that the people I daven with, I cannot talk to, and the people I talk to I cannot daven with. However, when the chips are down, I will always side with the people I daven with for I can live without talking. I cannot live without davening.

But the truth is that nearly any idiosyncratic thinking Orthodox Jew can relate to the first sentence of the bolded paragraph, if not only 'Orthoprax' Jews. What people choose to do with the dilemma is another matter. Calling it a personal tragedy may be dramatic, but I am sure I know what he means.

Friday, May 27, 2005

Hillel Halkin's review of the Etz Hayim Chumash

'Boiling a Kid': Reflections on a New Bible Commentary , By: Halkin, Hillel, Commentary, 00102601, Apr2003, Vol. 115, Issue 4

"IT IS a tree of life to those who lay hold of it," the book of Proverbs says--not of the Torah but of the vaguer concept of "Wisdom." Most Jews who know this verse are more familiar with it from the synagogue, where it is recited--sung, in many congregations--as part of the prayer that accompanies the return of the Torah scroll to its ark after the weekly reading from the Pentateuch.

Etz Hayim, "Tree of Life," is therefore an apt name for the new commentary on the Pentateuch, or Five Books of Moses, that was published over a year ago by the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism and its Rabbinical Assembly.(a) Prepared by a committee of eminent Conservative rabbis and scholars, it appears in a handsome oversize volume together with the biblical text in Hebrew and English--the latter in the 1985 translation of the Jewish Publication Society (JPS).

Etz Hayim is a more important book than the term "biblical commentary" might indicate. That is not only because, in addition to its gloss on the biblical text, it contains an appendix of 160 double-column pages of essays, by over 40 contributors, on the Torah and contemporary ways of reading it. It is also because biblical commentaries are a time-honored way of presenting a cohesive view of Judaism. Apart from Philo of Alexandria in the 1st century C.E., whose influence on later Jewish thought was nil, systematic philosophies of Judaism are a relatively late development in Jewish life, beginning only in the Middle Ages. But unsystematic ones can be found, starting with the 4th century C.E., in the verse-by-verse exegeses of the Torah that the rabbis compiled in numerous midrashic books, as well as in similar biblical commentaries in such classics of Jewish thought as the great 13th-century kabbalistic work, the Zohar. Etz Hayim takes its place in this tradition. Although nowhere in it is there stated a comprehensive credo for Conservative Jews, its many pages ultimately add up to one.

The publication of Etz Hayim is thus a noteworthy event, especially because the American Conservative movement, the largest of American Jewry's three major religious denominations, has often been accused of having no clear theological positions of its own and of defining itself more as a tertium quid between what it is not--i.e., Orthodoxy or Reform--than by what it is. (Historically, indeed, this was precisely how the Conservative movement began in America with the founding of its institutional flagship, the Jewish Theological Seminary, in 1886.) The old quip that an Orthodox Jew walks to synagogue on the Sabbath, a Reform Jew drives to it, and a Conservative Jew parks at a safe distance reflects the widely held perception that, whereas Orthodoxy and Reform stand for clear principles, Conservatism stands for fuzzy compromises--a perception that may only have been strengthened by the 1988 "Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism" known as Emet ve-Emunah, "Truth and Faith." Nor, though the movement has had its major theologians, does their thought represent a coherent stance. One could hardly imagine more different approaches to Judaism than the sociological rationalism of Mordecai M. Kaplan and the subjectivist existentialism of Abraham Joshua Heschel, the movement's two most notable 20th-century thinkers.

Conservative praxis has been no less confusing. Whereas Orthodoxy and Reform have been consistent in their attitude toward rabbinic law, the former affirming and the latter denying its authority for the modern Jew, Conservatism appears to have waffled. Does, for instance, a sincere commitment to Judaism require one to observe the traditional Sabbath or dietary laws? Yes, says Orthodoxy. No, says Reform. Conservatism--at least in the eyes of its critics--says Maybe.

And Etz Hayim? The biblical dietary laws are one of the subjects of the portion of Leviticus called Shemini, the Torah reading for the week in which this issue of COMMENTARY may be arriving in the mailboxes of many of its subscribers. So let us look at Etz Hayim's treatment of these laws in Leviticus 11.

"THESE ARE the creatures that you may eat from among all the land animals: any animal that has true hoofs, with clefts through the hoofs, and that chews the cud," begins Leviticus 11 in the JPS translation. Then it lists several prohibited mammals, like the camel and pig, that meet only one of these requirements; proceeds to aquatic creatures ("anything in water ... that has fins and scales, these you may eat"); and ends with birds and "winged swarming things."

Etz Hayim's remarks on the 47 verses of this passage are divided--as is the new commentary in general--into three sections. The first, printed directly beneath the biblical text and called the "P'shat," the rabbinic term for "literal meaning," seeks to elucidate that meaning in the light of modern biblical scholarship. The second, appearing below the P'shat and called the "D'rash," a word used by the rabbis to refer to a text's implied or logically or imaginatively deducible content, gives a Conservative view of the significance of Leviticus 11 for the modern reader. A third section, named "Halakhah L'Ma'aseh," or "Practical Halakhah" (Jewish religious law), comes at the bottom of the page and comments on the ways in which the biblical dietary commandments were later amplified in rabbinic law.

For example: looking at the P'shat on the two verses beginning, "These are the creatures that you may eat from among all the land animals," we are told by Etz Hayim that the Hebrew word for "creature" (hayah) is a "general term" while that for "land animal" (behemah) is more specific, and that "To qualify as pure, an animal's hoofs must be split all the way through, producing two toes, of a sort, so that the animal in question does not walk on paws." Jumping to the bottom of the page, we read in the Halakhah L'Ma'aseh section, under "any animal":

For meat to be kasher ("kosher," fit for consumption under Jewish law), it must not only come from the animals designated in this chapter (e.g., cows, sheep, goats, buffalo, and deer), but must also be slaughtered, soaked, salted, and prepared according to Jewish law.

But the most interesting part of the commentary on these two verses is the D'rash. It begins as follows:

An attentive reading of this chapter clearly shows that the dietary laws are not based on considerations of health.... The dietary laws constitute a way of sanctifying the act of eating. The eating of meat requires killing a living creature, constantly seen by the Torah as a compromise. These laws elevate the eating of meat to a level of sanctity by introducing categories of permitted and forbidden. For animals, eating is a matter of instinct; only human beings can choose on moral or religious grounds not to eat something otherwise available.

It then continues:

The dietary laws are given incrementally in the Torah: forbidding boiling a kid in its mother's milk; then prohibiting the ingestion of blood; then declaring certain species of mammal, fish, and fowl unfit for consumption. Similarly, many Jews who begin from a position of limited observance can commit themselves to sanctifying their mealtimes in an incremental manner. They may begin by avoiding pork anti shellfish, continue by separating meat and dairy products, and so on. No one need feel like a hypocrite for not keeping all of the commandments immediately. What is important is to be on the path of observance, to be, in the words of Emet ve-Emunah ... a "striving" Jew.

THE INNER dialectic of this D'rash is subtle. It begins in the unstated context of an ancient rabbinical debate, already lively in talmudic times and sharpened in the Middle Ages, over whether some or all of the ritual commandments of the Bible have a utilitarian explanation (the great 12th-century philosopher Maimonides, for example, thought the dietary laws had in part a hygienic intent), or whether they are best viewed as arbitrary decrees whose sole purpose is obedience to the divine will. Etz Hayim opts for the latter view. The Bible, it says, declares certain animals edible not because they are healthier than others, or indeed because they are healthy at all, but because eating should be a religious act embodying principles of discrimination.

The next move in the D'rash--again without calling attention to the rabbinic background--is to mobilize a tradition, found in medieval commentators like Rashi and Nahmanides, that Adam and Eve were vegetarians in the garden of Eden and that meat-eating was a consequence of the expulsion from paradise. The D'rash does this by stating that the dietary laws, despite sanctioning certain animals as food, actually represent a "compromise" between a biblical ideal of abstention from meat and man's baser nature. Concisely and elegantly, Etz Hayim thus weaves several strands of rabbinic thought into the suggestion that the biblical attitude toward meat-eating is, apart from its concession to human frailty, not very different from the currently fashionable criticism of the raising of animals for slaughter and consumption.

Even bolder, however, is the remainder of the D'rash--for here, still using rabbinic interpretive method, Etz Hayim breaks with basic rabbinic norms. Taking as its point of departure the "incremental" presentation of the dietary laws in the Torah--the ban on boiling a kid in its mother's milk, from which the rabbis derived the inadmissibility of mixing meat and dairy, is first stated in Exodus 23, while that on eating blood does not appear until Leviticus 3(b)--Etz Hayim allegorizes this into a prescription for their incremental observance. A Jew resolving to keep the rules of kashrut, it suggests, might start by dropping the bacon with his eggs, then cut out cheeseburgers, and finally give up non-kosher meat entirely. Meanwhile, he need not "feel like a hypocrite," since what matters is that he is trying.

It must be said that there is nothing in rabbinic tradition to justify such an approach. To be sure, when it comes to what the rabbis call mitzvot aseh--mandated acts whose omission, though regrettable, is not deeply sinful--incrementalism may be acceptable. If a Jew, who is enjoined to pray three times a day, manages to pray only once, this is indeed better than not praying at all. But mitzvot lo ta'aseh--acts expressly prohibited--are something else. From the point of view of halakhah, a pickpocket who decreases the number of wallets he steals from three to one daily has not become less of a thief, nor does abstaining from some prohibited foods while knowingly eating others make one a greater observer of the dietary laws. On the contrary: whereas the thief may be able to plead extenuating circumstances, such as the need to make a living, the no-bacon-but-cheeseburger Jew has no excuses. Judged by traditional Jewish standards, a "hypocrite," not to say a sinner, is exactly what he is.

Etz Hayim on Leviticus 11 is thus contemporary in its bow to vegetarianism (elsewhere, it is even more outspokenly au courant in its feminism); classically Conservative in its central message (Jewish ritual observance is good for you, but everyone must decide on his own dosage); compassionate in its wording (who would not rather be a "striving" than a sinful Jew?); and profoundly enigmatic in the questions it poses. Is giving up bacon before cheeseburgers called for because the prohibition on pig meat is biblical while that on mixing meat and dairy is merely rabbinic? If so, is swearing off bacon obligatory for the "striving" Jew, or can he be a striver while eating it, too? And why should biblical law matter more than rabbinic law, anyway? Because the Torah is a divinely revealed document while rabbinic law reflects human endeavor? But what does "divinely revealed" mean to Conservative Jews? And if rabbinic law is not also--as it is for Orthodoxy--a manifestation of God's will, why obey it at all? Why not take the classical Reform position that modern Jews are free to disregard it?

These are not trivial questions. They are the very questions to which critics of the Conservative movement, both on its religious "Left" and on its religious "Right," have repeatedly accused it of fudging the answers. Let us see how Etz Hayim deals with them.

"NOW MOUNT Sinai," say verses 18-19 of Chapter 19 of the JPS version of the book of Exodus, "was all in smoke, for the Lord had come down upon it in fire; the smoke rose like the smoke of a kiln, and the whole mountain trembled violently. The blare of the horn grew louder and louder. As Moses spoke, God answered him in thunder."

There follow what are known as the Ten Commandments. Immediately after them begin the extensive legal regulations of the Pentateuch. But what does the Torah mean when it says that God spoke on Mount Sinai, and how are we to understand what happened there? A thinking Jew's opinion about this matter must surely determine how he relates to the entire question of Jewish observance--which is perhaps why there has never been a clear Conservative position on it. Etz Hayim attempts to give us one.

The first thing to observe here is that Etz Hayim does not question that something did happen at Sinai. Since the second half of the 19th century, many Bible scholars have grouped the Sinai story with other supposed "legendary" episodes in Scripture, such as the tales of the patriarchs in the book of Genesis; by contrast, the Etz Hayim commentary sides with more traditionalist scholars in assuming that these narratives have a historical basis. The only actual discussion of the issue occurs in the book's separate section of essays, in a cautious presentation of "Biblical Archeology." There, writing about the Bible's account of Israel's bondage in and exodus from Egypt, of which the Sinai story is part, Lee Levine observes that while "[t]here is no reference in Egyptian sources to Israel's sojourn in that country, and the evidence that does exist is negligible and indirect," nevertheless "these few indirect pieces of evidence ... do suggest a contextual background for the Egyptian servitude (of at least some of the people who later became Israelites) and the appearance of a new population in Canaan." Which is to say that, if one wishes to believe that there indeed was an exodus and a dramatic convocation at Mount Sinai, there is no scholarly hindrance to doing so.

Etz Hayim, at any rate, does wish us to believe it-up to a point. The location of this point is already partly fixed by the JPS translation on which it relies. This, though not an official Conservative document, was largely the work of rabbis and scholars associated with the Conservative movement. One minor peculiarity is its version of Exodus 19:19: "As Moses spoke, God answered him in thunder." The Hebrew preposition-plus-noun translated as "in thunder," b'kol, is inherently ambiguous, because elsewhere in the Bible the word kol can mean "voice," "sound," or indeed--but only in its plural form--"thunder." "Thunder" is almost certainly what the plural form of kolot does mean several verses previously, in 19:16, where we read, "On the third day, as morning dawned [on Mount Sinai] there was thunder [kolot] and lightning." Yet nearly all traditional Jewish translations and commentaries, from the third-century B.C.E. Greek Septuagint to the previous JPS translation of 1917, have taken kol in 19:19 to denote--however this is conceived of--God's voice.(c)

This is a consequential point. Here is what Etz Hayim's P'shat on Exodus 19:16-19 has to say about God's thunder on Mount Sinai, along with the fire and smoke:

Violent atmospheric disturbances are said to precede and accompany the theophany. The Bible frequently portrays upheavals of nature in association with the self-manifestation of God.... The vivid, majestic, and terrifying depiction that draws its inspiration from natural phenomena, such as the storm, volcano, and earthquake, is meant to convey the awe-inspiring effect of the event on those who experienced it.

In other words, Etz Hayim is telling us, not only was there, literally speaking, no voice of God at Sinai, there was not necessarily any thunder, either; such "vivid, majestic, and terrifying" depictions can be considered metaphors employed by the author of Exodus "to convey the awe-inspiring effect of the event." What, then, happened there? All we are left with, it would seem, is an "event" of which no more can be said than that it took place.

Of course, this may be an unavoidable way of looking at that event, even from the point of view of a "traditionalist" scholar. If, on the one hand, something that occurred over 3,000 years ago at a mountain in Western Asia deeply affected the lives not only of those who experienced it but of all the generations of their descendants, it must have been very powerful; on the other hand, given all that we know about the human memory and imagination and their ability to reshape the past within even brief spans of time, what can possibly be affirmed about the substance of this "something" other than that it is unknown and unknowable? Rationally, such agnosticism is unexceptionable--and yet, as an explanation of why this makes the Torah a divinely revealed book to whose laws Jews owe their allegiance, it is, to say the least, problematic.

THE EDITORS of Etz Hayim appear to have been well aware of this. That is why, one presumes, they have included in the essay section three different treatments of "Revelation." All three are thoughtful and harmonize with one another.

Thus, for example, on the subject of "Revelation: Biblical and Rabbinic Perspectives," Daniel Gordis observes:

The Torah does not specify precisely what was revealed to Moses.... It is striking that the Torah seems more concerned that the people Israel accept the notion that revelation took place than that they reach any certainty about the content of that revelation.

This is seconded by Elliot Dorff in an essay on "Medieval and Modern Theories of Revelation." "The Torah itself," Dorff writes, is ambiguous as to how much of God's revelation the people heard. Some rabbinic interpretations (e.g., Exodus Rabba 5:9) go so far as to point out that at Sinai each person understood God's revelation in his or her own way, depending on each individual's intelligence and sensitivity.

And Dorff continues, after discussing the "God-encounter" theology of the two German-Jewish thinkers Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig:

The revelation at Sinai is critically important because that is where our ancestors as a people first encountered God and wrote their reaction to that event in the document that became the constitutive covenant between God and the Jewish people.... Each time we read the Torah anew, nothing less than God's revelation is taking place again.

With which Jacob Milgrom, finally, discussing "The Nature of Revelation and Mosaic Origins," concurs by writing that "revelation was not a onetime Sinaitic event."

But if revelation is taking place all the time--if it occurs whenever we "encounter God"--this hardly elevates our experience to the level of what the Bible says happened at Sinai but rather reduces our sense of what happened at Sinai to the level of our own experience. At most, then, the difference between Sinai and those moments in our lives when we feel a communion with something sacred or transcendent is a matter of degree. Although the biblical event may have been more intense, or shared by more people, it was subjective, just like our own. Why, then, should a Jew accept its authority?

It can be argued, perhaps, that what is simultaneously experienced subjectively by a large number of people becomes an objective fact, so that Sinai is unique as a revelatory moment because its "God-encounter" was participated in by all Israel. This is the meaning Elliot Dorff seeks to extract from the midrash in Exodus Rabba to which he alludes and which--in commenting on the presence of both the plural and singular forms of kol in the biblical account--is indeed startlingly bold:

Rabbi Yohanan says: A voice [kol] went forth and was divided into 70 voices [kolot] for the 70 languages of the world.... Rabbi Tanhuma said:... Come see how one voice went forth to each person in Israel and each understood it according to his capacity--the elderly men according to theirs, and the young men according to theirs, and the children according to theirs, and the infants according to theirs, and the women according to theirs. And even Moses [understood it] according to his, for it is written, "As Moses spoke, God answered him in a voice [b'kol]"--in a voice that he was capable of receiving.

And yet, as Rabbi Tanhuma might say, come see the difference. Exodus Rabba tells us that even the thunder heard at Sinai was the 70 or the 600,000 voices of God speaking at once (600,000 being the number of Israelites said to have been at the foot of the mountain). The JPS translation, with the backing of the Etz Hayim commentary, tells us that even God's one voice was nothing but thunder--if that!

LET US accept the sincerity, if not the logic, of Elliot Dorff's contention that it makes no real difference "whether God spoke words at Sinai, or whether God inspired human beings to write down specific words, or whether human beings wrote down the words of the Torah in response to their encounter with God in an attempt to express the nature and implications of that encounter." In all these cases, he argues, "the authority of the Torah's revelation is, in part, divine." Let us not even pause here to ask whether the words "in part" might render the whole proposition meaningless. Let us assume that they do not, and that the "parts" of the Torah whose authority is divine include Leviticus 11. Bacon, then, is out. But why cheeseburgers?

The biblical "proof" offered by the rabbis for the ban on mixing meat and dairy is discussed in the talmudic tractate of Hulin. It is based on the fact that the commandment, "You shall not boil a kid in its mother's milk," occurs, identically worded, in three different places in the Pentateuch--twice in Exodus and once in Deuteronomy. Since it is an axiom of rabbinic thought that the Torah is a single, seamless document given to Moses in which there is not an unnecessary or redundant word, the question must be asked: why is the prohibition repeated three times?

The answer given in the Talmud is that its first occurrence refers to cooking the kid with milk, the second to eating it with milk, and the third to deriving any benefit from such a dish, such as by selling it to a non-Jew. And how do we know that these three-bans-in-one apply not just to goats but also to other domestic ruminants such as cows and sheep? Because, Rabbi Akiva says of the same triply repeated prohibition, of what it excludes. The first time it appears, we may understand it to be excluding from its jurisdiction non-domestic ruminants like deer; the second time, poultry (which according to some ancient rabbis was edible with milk); and the third time, non-kosher animals like pigs (which cannot be eaten by Jews even without milk, of course, but which can be cooked by Jews with milk and sold--as in a restaurant--to non-Jews). By a process of elimination, then, domestic ruminants fall under the ban.

Such argumentation, needless to say, strikes the modern mind as far-fetched--and indeed the rabbis themselves, cognizant that many of their halakhic interpretations seemed to stray far from the apparent intention of the biblical text, felt called upon to justify their procedures. They did so by declaring that the vast compendium of the "Oral Torah"--their term for rabbinic law--was given at Sinai together with a far more concise "Written Torah" in which it reposes immanently, as it were, and from whose maximally terse because perfect language it must be teased out by logical method. Numerous midrashim exist to illustrate this belief, one of the best-known being a story about Moses and Rabbi Akiva that is cited by Jacob Milgrom in his essay on revelation.

In this story, Moses is magically transported in time to a lesson in Akiva's classroom, in which he sits without understanding a word of what is being said. (Could the subject, possibly, have been meat and milk?) Crestfallen at both his mental insufficiency and the apparent neglect of his teachings, he brightens when Akiva, asked "Master, where did you learn this?" by a student, replies, "It is a law given to Moses at Sinai." The story, Milgrom ob serves, "portrays the human role throughout the generations in the revelatory process.... It behooves and indeed compels each generation to be active partners of God in determining and implementing the divine will."

This midrash is both profound and charming, though its ending, omitted by Milgrom, takes a somewhat darker view of the human "partnership" in "implementing the divine will." (The story concludes with Moses being vouchsafed a vision of Akiva's martyrdom by the Romans. "Master of the Universe," he asks, "is this the reward for studying Torah?" To which God answers inscrutably: "Be silent, for so I have decreed!") But while, as parable, the story makes perfect sense in the traditional rabbinic context, in the context of Etz Hayim it makes none. This is because Etz Hayim, in its acceptance of modern biblical scholarship, explicitly does not view the Torah as a seamless document.

Here is how the volume's senior editor, David L. Lieber, puts it in his introduction:

Conservative Judaism is based on rabbinic Judaism. It differs, however, in the recognition that all texts were composed in given historical contexts. The Conservative movement, in short, applies historical, critical methods to the study of the biblical text. It views the Torah as the product of generations of inspired prophets, priests, and teachers, beginning with the time of Moses but not reaching its present form until the postexilic age, in the 6th or 5th century B.C.E.

But one conclusion of "historical, critical method" is that the book of Deuteronomy was written by a different hand from the one that wrote the book of Exodus. If that is the case, then the Torah's triple repetition of "You shall not boil a kid in its mother's milk" cannot be considered to represent a deliberate authorial strategy, much less be used as a basis for a complex process of logical deduction. How, then, can the ban on mixing dairy and meat be thought of as "a law given to Moses at Sinai?"

SO CHEESEBURGERS are all right, after all? No, they are not. We have already seen that Etz Hayim counsels the reader to aim at eliminating them from his diet. It simply never explains coherently why, not even after we have considered the several reasons advanced by Edward Greenstein in his essay on "Dietary Laws." There, Greenstein writes that the ban on mixing dairy and meat is a way of expressing a "reverence for life," since it tells us that "milk, which is meant to sustain life, may not be turned into a means of preparing an animal for eating." In addition, while "the system [of kashrut] may appear artificial and arbitrary ... the Torah has the community [of Israel] make distinctions, just as God did in creating the world.... Following in God's footsteps, so to speak, conveys holiness." And finally: "A people maintains its ethnic identity by eating differently.... [T]he heroes of Jewish narrative display their loyalty to their religious tradition and to their people by observing the dietary laws."

None of these defenses of kashrut invokes the authority of either the Torah or the rabbis. All, rather, are based on the supposition that the dietary laws are good for the individual Jew and the Jewish people on spiritual, moral, and national grounds. This sounds very similar to the utilitarian arguments on behalf of Jewish observance put forth by a thinker like Mordecai Kaplan in such works as Judaism as a Civilization (1934) and Judaism Without Supernaturalism (1958). Hardly a religious believer in any ordinary sense of the word, Kaplan, who was deeply influenced by the pragmatic perspective of the Hebrew writer and social philosopher Ahad Ha'am, viewed religious practice not as an end in itself but as a means of preserving and inculcating the values of Judaism in a modern, scientific world.

Indeed, if Kaplan and A.J. Heschel, the latter influenced by Buber and Rosenzweig, represent the two poles of "Left" and "Right" between which the thought of the Conservative movement has swung, these poles mark the boundaries of Etz Hayim, too. On the one hand, there is the ineffable (a favorite word of Heschel's) moment at Sinai, where something of enormous significance took place that cannot be described in itself but only in terms of its consequences. And on the other hand there are the consequences, which cannot be justified in terms of Sinai but only in themselves. In between is a gap that, even if 1,560 intelligent pages attempt to bridge it, refuses to disappear.

Etz Hayim gives us many reasons why a modern Jew should not eat cheeseburgers, but many reasons are needed only when a single, compelling one does not exist. Nor, in the final analysis, will all the admirable thought and effort that have gone into Etz Hayim convince many Conservative Jews either to walk to synagogue on the Sabbath or to stop feeling vaguely guilty for driving. If the new Bible commentary proves anything, it is that Conservatism is a movement of inconsistency and compromise not just at the practical but at the highest intellectual level. It remains precisely what it has always been and has resented being called: neither Orthodoxy nor Reform.

Yet this also remains the source of its strength. For it is as such a vaguely defined middle ground that the 40 percent or so of all synagogue-affiliated American Jews who belong to Conservative congregations would appear to view themselves. Compromise is often messy and rarely satisfying, but it is the stuff of life. How strenuously can one object to its being the stuff of the Tree of Life?

(a) Edited by David L. Lieber, Jewish Publication Society, 1,560 pp., $72.50.

(b) Although a prohibition on eating blood is already issued by God to Noah in Genesis 9:4, it does not appear there as part of Mosaic law.

(c) This is also the wording of the King James Bible. To the best of my knowledge, the only previous English Bible translation to assume that kol can mean "thunder" in the singular and to render it as such in this verse is the 1952 Revised Standard Version of the National Council of Churches.

Thursday, May 26, 2005

On playing chess.

Sounds nice. Obviously his idea does not preclude other benefits, such as teaching one how to think like a Talmudist. I wonder what y'all think.

Bruce Springsteen? Not a godol, apparently.

This isn’t hagiography; it’s unadorned fact. We live with them, study under them, interact with them, observe them. The throngs at funerals of authentic Jewish leaders are no surprise: they genuinely love us and we love them back.But then he loses me. I don't know if Bruce Springsteen does or doesn't have empathy or if he does or doesn't do personal acts of kindness. But I am not sure how the following is warranted:

Don’t misunderstand: Producing songs that tell of the misery and mistreatment of Mexican farm workers is commendable, certainly when it gives them a voice and brings attention to their plight, and particularly when contrasted with what preoccupies most other performers and their artistic output. But it’s far, far from aproaching the pinnacle of moral greatness.Why is calling attention to the plight and misery of thousands of reduced moral worth? Do we really need to diminish others to elevate our own? I have never heard of a gadol who moved to the third world to bathe and service pagan lepers, yet that is what Mother Teresa devoted her life to. Just as her awesome service to her fellow man* doesn't diminish acts of tzidkus from our own gedolim it shouldn't be necessary to diminish the acts of others to elevate our view of them.

*I am aware that there are conflicting accounts of her righteousness. I know nothing about that; she is only an example.

Wednesday, May 25, 2005

No one thinks Chazal were infallible. But some do think the following...

They would say they definitely do not agree that any human, including Moshe and including any of Chazal were infallible. But they insist that their view of them isn't that they were infallible but rather that all that they said that was recorded for posterity in the Talmuds and Midrashim are faithful recollections of Torah that God said to Moshe at Har Sinai. Thus, they are not infallible. But their words which we have -- on any subject, be it halakha, history, medicine -- came from God's mouth, kavyachol, to Moshe's ears and to our ears.

In fact, there is a prevalent opinion that Torah she-b'al peh and the chain of masorah means that any chiddush said by any respected rabbi who ever lived was said by Hashem to Moshe. Thus, for example, if the Malbim said a peshat that would mean that he heard it from his rebbe who heard it from his rebbe in a chain going back 135 generations or so and was literally said over to Moshe by Hashem. That the peshat was first published in the nineteenth century? No bother. That is definitely a view some people have.

Yesh chokhma bagoyim ta'amin and what it means to us.

The explicit systematic discussions of Gentile thinkers often reveal for us the hidden wealth implicit in our own writings. They have, furthermore, their own wisdom, even of a moral and philosophic nature....There is chokhmah begoyim, and we ignore it at our loss. Many of the issues which concern us have faced Gentile writers as well....To deny that many fields have been better cultivated by non-Jewish writers, is to be stubbornly--and unnecessarily chauvanistic. There is nothing in our medieval poetry to rival Dante and nothing in our modern literature to compare with Kant, and we would do well to admit it. We have our own genius, and we have bent it in the noblest of pursuits, the development of Torah. But we cannot be expected to do everything.

See how wonderfully experience confirms this. We observe that many words, when one says them in Hebrew, fail to make any kind of impression. When he translates them into German, they make more of an impression. At first I thought the reason is that Hebrew is not, for us, the mutter sprach (mother tongue). But now it seems more plausible according to our approach: the Hebrew word we received in childhood without a distinctive flavor and aroma [italics mine]. For example, the word Torah spoken in Hebrew does not make the same impression that it does when we translate it into German as Bildung. Why? Because we associate the word Bildung (education) with the savor of wisdom. The word Torah we do not associate with the savor of wisdom, because as children we knew nothing of the savor of wisdom....An Apology for Yirat Shamayim in Academic Jewish Studies".

Taken from R. Shalom Carmy's excellent essay "

Monday, May 23, 2005

Turn in tune out

Reconciling the irreconcilable

Friday, May 20, 2005

A bold statement from Marvin Schick.

His point is hardly new, but what is noteworthy is that it is a post on Cross-Currents and not a comment in one of the threads.

Thursday, May 19, 2005

Someone asked me what my deal is. Here is some of it.

I went to a name brand mesivta that I decline to name. I suppose it is pretty centrist for a yeshivish yeshiva. Bachurim are allowed to go to college at night, much to the present roshei yeshivos' chagrin. Apparently the founding rosh yeshiva allowed it and there's just no way for them to stop it. But if you went, you definitely couldn't have been considered one of the top guys. And when I was in twelfth grade our mashgiach gave us a schmuess where he read from a famou letter by R. Baruch Ber (to the unnamed young R. Shimon Schwab) forbidding college, full stop. The implication was clear. But I did go to college anyway when I was at that yeshiva.

I was always interested in history and hashkafa. I read a lot. I would discover books in my parents house, things like 'Rejoice O Youth' by R. Avigdor Miller (a sort of modern day yeshivish Kuzari, if you haven't read it). 'This Is My God' by Herman Wouk, which I love. I also read books like 'The Indestructible Jews' by historian Max I. Diament, my first brush with an apikorshise view of Jewish history, so to speak. That confused me, but I could compartmentalize, the same way I could read about "millions of years ago" and evolution and dismiss it as obviously untrue yet read it as if it was. I would say that in high school I was a bit more clued in than the average bachur, but not substantially more so.

When I was in college I took a couple of Judaic studies classes. One was given by a fairly prominent Jewish academic. Needless to say it was pretty radical for me to be sitting in a college learning Rambam with girls (and the odd guy from Nigeria). The professor glibly asked once if we knew what the "theme" of a certain book in Nach was. If we knew what the difference between Yirmiyahu and Yeshayahu was. Don't make me laugh, you know? I knew a shev shmaytza, but Jeremiah? That realization bothered me. Why was I, nearly twenty and with a decade and a half of yeshiva education, so ignorant?

So I began to read more. I cultivated an interest in R. Aryeh Kaplan and his Torah u-madda without the name approach. I discovered R. Samson Rafael Hirsch. You mean there is a mainstream, unapologetic position that Torah and culture ought to proudly coexist? I actually read the Hertz Chumash (believe it or not, it wasn't until I heard Nosson Scherman describe it as "heroic" that I thought it might be worth looking at). I read R. Aryeh Kaplan's 'The Living Torah' translation and was absolutely floored by its bibliography, or the idea of it.

Basically I gradually came to hold a sort of Torah U'Madda view, without knowing it, and without having shaken of my prejudices against it. After leaving the yeshiva I learnt for several more years in a different yeshiva, more open in some ways because it had a more diverse student body. The mashgiach there gave a schmuess once about how Torah U'Madda is wrong since anything with "Torah AND" is krum. Kindly explain why "torah and" is worse than "torah with", I should have asked. But I didn't, since I kind of agreed with him then.

It took a while before I could realize that, you know, the fact that the Jastrow dictionary is in widespread use in yeshivos means something and was actually a victory of the haskalah, in fact. That all sorts of non-Jewish and non-frum sources are and were regularly used to illuminate Torah by all sorts of impeccable Torah personalities--these mean something. It means that there is value and truth apart from a very narrow, ideological confine.

I remember once telling a certain distinguished rosh yeshiva (a "godol" in the making, by any reckoning) what I thought was a nice peshat in the Akeda. It went something like this. Hashem commanded Avraham to sacrifice Yitzhak, but an angel had him desist. Who was the angel? None other than Avraham's yetzer ha-tov!

Who said this vort? Alan Dershowitz's nine-year old daughter, as recounted in his book 'The Genesis of Justice'. I also told this rosh yeshiva another vort that I read in that book. Why did Adam listen to Eve? True, Eve had a smoothe-tongued serpant seducing her. But Adam only had Eve. Why would he have listened to her and not God? Answered Dershowitz, Adam wasn't convinced by her. But he knew that she would be exiled from the gan, and he knew his place was with her, so he ate. Very romantic.

Well, this RY absolutely loved these two peshats. I didn't tell him where I got them from, I pretended to forget. That was a test I devised for myself, to see if the injunction to accept the truth from wherever it comes is true. Had I told him the source? Its possible he'd have done a 180. But to me it was a satisfactory proof that you can find a shtik Toyrah in surprising places.

It took a long time to shed earlier prejudices. I am almost scandalized now how I first felt when I discovered Nehama Leibowitz. I liked what I was reading but I felt a visceral reaction to it simply because she was a woman -- and I considered myself to be a feminist, at least in the sense that women should not have their opportunities hampered and should be paid equal wages and so forth. Yet, there I was not being able to digest Torah being taught by a woman. Even though I knew that women taught Torah to women and never would have thought that what they were teaching wasn't real. But the idea of a man learning Torah from a woman -- that just didn't make sense to me. My reaction was emotional and without any solid basis. There was a whole world I had no clue about.

I felt the same way when the whole Making of a Godol thing was brewing. Imagine my shock to learn that not only had R. Yaakov read Anna Karenina (as had I -- booooring) but he was apparently shocked that the bachurim in Torah V'Daas hadn't. And these are just two minor examples of many, many more shocks.

Frankly, when you open up your eyes and realize the edifice of ignorance that has been constructed you have no choice but to investigate further. And my experience has obviously not unique by any stretch.

Monday, May 16, 2005

A brief and tentative history of Mishna and Gemara

Compiled or edited or published -- it is uncertain -- by R. Yehuda ha-Nasi in the early 3rd century C.E., the Mishna is not a law code. It invariably cites multiple opinions and does so specifically so that subsequent generations can examine all sides of the issue and pasken for themselves. However oftentimes the Mishna will in fact give preference to an opinion. Sometimes explicitly and sometimes one has to know the code. For example, if a Mishna gives an opinion without attribution -- a stam mishna -- it is not necessarily because the author of the opinion was unknown to R. Yehuda. On the contrary; often the same anonymous opinion is found with attribution in the Tosefta. When an anonymous opinion is given it is because R. Yehuda wanted to highlight that opinion and let is stand on its own, as it were. That is the opinion that R. Yehuda wanted to give preference to. Other times "the code" is that the halakha is always like specific authorities when they are named. Thus we find that when something is attributed to the early tanna R. Eliezer ben Ya'akov we pasken like him. Other times there are rules of how we resolve disputes between authorities. Thus we will pasken like Beis Hillel in their disputed with Beis Shammai, with relatively few exceptions. We will generally pasken in accordance with the chachamim, i.e., a majority of rabbis, when they are disputed by a minority.

When all is said and done, the Mishna is a syllabus. And that is precisely how it was used by the amoraim, the sages of the Gemara, in their academies.

The amoraim analyzed, debated and [insert a half dozen other terms like that here] the halakha, always mindful of the mishna (as well as other tannaitic literature, such as the Tosefta). The amoraim sought to ground the Mishna in Scripture. They demonstrate how the halakha of the Mishna is in fact derived from Tanakh. Thus, to revisit that first mishna in Berachos, the Gemara does not take it as given that there is an obligation to recite shema at night. The Gemara needs it to be proven from Scripture, and prove it it does. That is the MO of the Gemara. In its analysis of the Mishna and tannaitic statements it meticulously provides the sources in Tanakh as well as the exegetical method used to derive those laws from Tanakh itself.

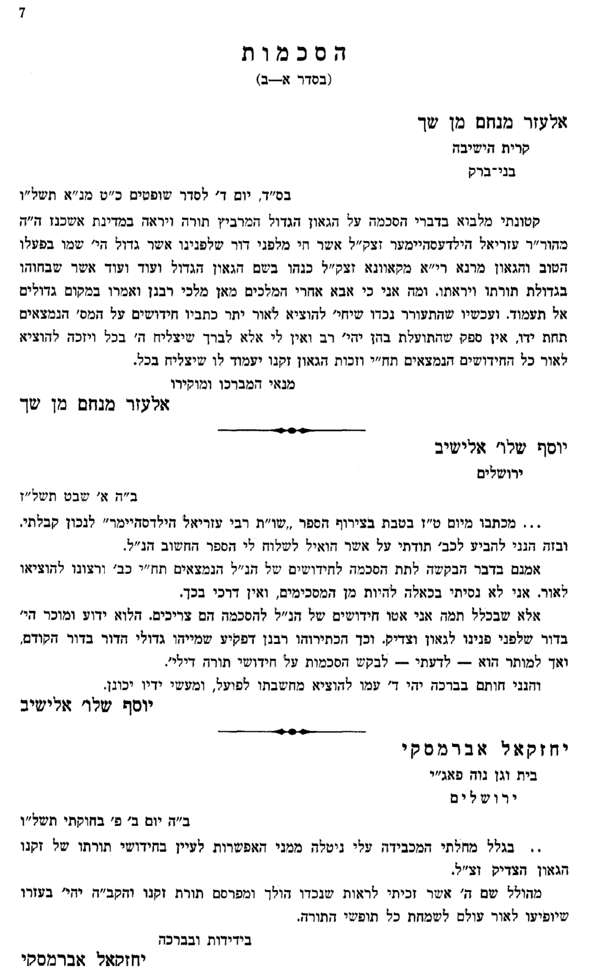

Thursday, May 12, 2005

R. Shach on R. Azriel and what it means

I am not of sufficient stature to provide a letter of approbation for the great Gaon, disseminator of Torah and fearer of the Lord in Germany, our master, Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer, of blessed memory. He lived in the generation that preceded the previous generation; great was his fame due to his good deeds. The Gaon R. Yitzhak Elhanan of Kovno referred to him as "the great Gaon;" many others praised him for his greatness in Torah and for his fear of God. Who am I to follow in the footsteps of kings? (Who are "the kings"? The rabbis.) Moreover, it is stated in Scripture: Do not stand in the place of nobles (Proverbs 25:6). Now that his grandson has undertaken to publish his (i.e., R. Hildesheimer's) novellae on various tractates of the Talmud, we wish him every success.... May the merit of his grandfather, the Gaon, assure him every success in every matter.

R. Eleazar Menahem Shach

(Haskama to 'Hiddushei Rabbi Azriel: Yevamos, Kesubos', Jerusalem 1984)

R. Azriel Hildesheimer was a contemporary of R. Samson Raphael Hirsch. Unlike R. Hirsch, the Aruch Laner and other university-educated German rabbanim of the 19th century, R. Hildesheimer actually received a university degree (supposedly the first Orthodox rabbi to receive a doctorate is R. Nathan Adler who was Chief Rabbi of Great Britain). He was also a fellow traveler in the Torah im derekh eretz school.

He was a great educator, founding the famous Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary in Berlin; a rabbi factory, as it was derisively called by opponents of modernity.

Rabbi Marcus Lehmann -- who was the rabbi of Mainz, editor of Israelit and author of all those children's books; Akiva, Family y Aguilar et cetera -- was an early disciple of R. Hildesheimer. R. Lehmann preserved for us what the daily schedule was when being taught by R. Azriel:

Each morning R. Azriel lectured on poskim from 4 to 6 A.M. From 8 to 10 A.M. he lectured on tractate Gittin, and from 10 A.M. to noon he read German literature with [us]. From 2 to 4 P.M. he lectured on tractate Chullin, and from 8 to 10 P.M. he lectured again on posekim. On Sabbath we prayed at an early service, and then studied tractate Shabbat from 8 A.M. to 12:30 P.M. Friday evenings during the winter season he lectured on tractate Shavuot.

Esther Hildesheimer Cavalry remembered

On Yom Tov, between mincha and maariv, when no zemiros were sung, Father would seat himself in the large armchair in the bedroom, we children around him. I remember sitting at his feet on the footstool, with my brothers Levi and Aharon standing beside him, and Mother and the little ones on the sofa. Then Father would sing to us German "Lieder". And each time for us, his children, the high point was when he sang his favorite, Heine's "Die Zwei Grenadiere".

When R. Azriel died in 1899 his aron was brought into the synagogue because his successor, R. David Zevi Hoffman ruled that even though R. Avraham Danzig had ruled that doing that was only permissible for the Vilna Gaon, since he was unique in his generation, the same applied to R. Azriel who was unique in his generation and was

endowed with every good quality; sanctity, holiness, sharpness of mind, and erudition. He studied Torah day and night; sought diligently to observe the commandments and to do good deeds; strove mightily to work on behalf of the poor in the land of Israel and elsewhere; and fought bravely on behalf of our faith against its detractors...

He happened to have been of means and distributed his salary to the poor. In short, he was great. R. Shach well knew this. Did he know what precisely constituted his study and philosophy, his enjoyment of and singing secular German songs? I am guessing that he didn't know specifically but even if he did it would not have changed his opinion. R. Shach was a young boy when R. Azriel died and doubtlessly knew of his great name growing up. I am not certain however that he would have known every detail about how these great German rabbis lived, what they actually studied and incorporated into their lives etc. That said, it seems that the fact that a R. Shach could have this view of such a great man is revealing. What does it reveal? That not everything is black and white. Yet from reading other writings of R. Shach one would think that some of the things R. Azriel was "guilty of" would be yeharog ve-al ya'avor. Not everything is black and white; even the most black and white people aren't black and white.

Flogging that dead horse: fantastic midrash aggada.

The gemarah in Brochos descibes how one Tanna would perform miracles to prove his opinion was correct and although the Halacha was not like him it certainly must have been a consideration. Seems like the Halacha itself might have been influenced by the performance of miracles.

All I can say about this is that it is shocking that an adult who ostensibly studies can say this.

To refresh your memory, here he refers to perhaps the most famous aggada of all, the tanour shel achnai. This particular aggada is used by all sorts of characters to prove anything they like about Torah and halakha. That is not the point of it. Be that as it may the background is something like this. In the early centuries of the common era, Tannaitic times, people were concerned with tumah and tahara in a way that we are not today. There is a din that an earthenware keli will become tamei if it comes into contact with a source of tumah, like a dead sheretz. Unlike other materials used to make a vessel pure, earthenware cannot be made pure except by smashing it. They used to have outdoor ovens made of earthenware called tanours. That was a problem. Bugs could fall into it, as they must have regularly, rendering the oven tamei. And with no recourse but to smash it. It probably got very tedious constantly making new ovens. A lot of people probably said "to heck with this" and ignored it all together. Comes along a brilliant guy and invents a tanour oven that is made of pieces of earthenware that can be assembled and disassembled with ease. A solution? R. Eliezer ben Hyrcanus thought it was a great idea and he gave it his hashgacha (maybe it had an ben-HK symbol on it?). Not so fast, said the chachamim. We don't think this works at all. Still tamei. No good.

R. Eliezer was sure he was right. R. Eliezer tried to convince them with halakhic arguments. They weren't buying. R. Eliezer then invoked all sorts of miracles to support his view. He said, for example, "if I am right then let the carob tree prove it" and instantly a carob tree uprooted itself from the ground and landed a hundred feet away. The chachamim said "you can't pasken from a carob tree". He had water run the wrong way, the walls of the beis midrash practically collapse and even a heavenly voice declare that R. Eliezer was right. They said, essentially, "we don't pasken from water, from walls and not from a heavenly voice. The Torah says about itself, about the Torah, that it is lo bashamayim hi (Deut. 30:12). It basically doesn't matter what the din is in shamayim. The Torah says that we need to follow the majority in deciding halakhic matters and that is what we are doing. R. Eliezer, you are outnumbered: you lose."

To begin with, the obvious, simple peshat of this aggada is the opposite of what our friend suggested. Halakha is not influenced by miracles or even the pesak, so to speak, of Hashem. Lo bashamayim hi and all that jazz.

The Maharal explained that each of these miracles are actually references to specific sages that R. Eliezer succeeded in persuading to support his pesak. Thus, for example, the carob tree refers to the saintly R. Chanina ben Dosa, who subsisted only on carobs and so forth.

Perhaps the imagery in the aggada was inspired as well by certain realities. For example, it says that the walls of that beis midrash were in a strange fallen position to that very day. That was probably the case, that that specific beis midrash had sunken walls.

But what is almost certain is that the midrash is not suggesting that carob trees flew and re-rooted themselves or that R. Eliezer ben Hyrcanus had that ability. It must always be remembered that these midrash aggada came from actual speeches and lessons taught by the rabbis, in many cases to the common man. They used parables and other devices to attract their attention and make profound points that could be understood by the common man. And here we are 1800 or so years later and people apparently think that Tannaim could cause streams to flow backward. Sigh.

That said, it is not enough, in my opinion, to say that fantastic aggados are allegories. It is our obligation to mine those allegories for all that they're worth. Whether or not the Maharal was historically correct, that in the actual ma'aseh as it happened R. Eliezer went to R. Chanina and others is besides the point. He tried to connect the fantastic story with something tangible. In his view R. Eliezer convinced some of the greatest poskim of the day, yet was overruled since most of the chachamim had to be convinced and in that he did not succeed. If we will seek to understand the midrash ourselves it is not enough to grasp the point, that the Torah is lo bashamayim and that a majority is necessary for rendering proper halakha. We should strive to understand the imagery and examples as well. Why carobs? Why a stream? Why the walls et cetera.

Tuesday, May 10, 2005

They don't tell "stories" like that about you and me

Monday, May 09, 2005

There are four sons and there are four rabbis.

R. Chajes identified four types of inadequate rabbis.

About them R. Chajes wrote:

2) A second group consisted of rabbis who were well aware of their own failings and lack of skill in the art of debate. They feared public confrontation lest their lack of expertise bring dishonor to their cause.

3) Finally, a third segment of the rabbinate consisted of talented and learned individuals who enjoyed positions of prestige in the community but considered themselves to be above the fray and believed it to be beneath their dignity to engage in debate with individuals who were not their equals in rabbinic scholarship.

2) The ostriches; keep everything hush-hush and everything will be alright.

3) The insufficiently prepared and the cowardly.

4) The elitists.

Why does Artscroll say You shall not kill?

The Stone Chumash translates lo tirtzach as you shall not kill. As everyone and his uncle knows or should know, tirtzach really doesn't mean "to kill", it means something more along the lines of "to murder". While the notes at the bottom make it clear that Artscroll is presenting the rabbinic view that extends the prohibition of lo tirtzach to things such as humiliating people (which symbolically "kill" them, and are thus prohibited under this commandment) it seems to me an irresponsible translation given the fact that there is a common misconception that the commandment is "thou shall not kill". With this error comes a host of misinterpretation about the more nuanced view Biblical view of lawful killing (it doesn't flatly forbid the taking of human life) as well as polemics against the hypocrisy of a God that can command not to "kill" and yet encourages lots of killing elsewhere in the Torah.

It seems to me an irresponsible translation. I wonder what justification was used for this translation, apart from possible laziness? Surely the translator(s) was not ignorant of the impact of "kill" versus "murder" (or some more elegant way of phrasing it).

Beli neder in a future post I will give praise to what I feel is commendable about Artscroll, despite errors such as this.

Revising Shir Ha-shirim

That is why ArtScroll's translation of Shir HaShirim is completely different from any other ArtScroll translation. We translate it according to Rashi's allegorical interpretation.

Uhm, en mikra yotzi me-dei peshuto anyone?

Rabbi Yeyin tells it like it sort of was

Dateline: April 19, 2155. Rabbi Shmerel Yeyin sits down and is about to put finger to keyboard and begin writing his history of the Jews, Herald and Triumph: The Story of the Jews in the Postmodern Era from 2000 to 2150. Rabbi Yeyin, a popular writer and speaker on Jewish history, will of course discuss the Schottenstein edition of the Talmud (but not the Steinsaltz), the fact that more students studied Torah in this period during any earlier era in Jewish history, rebuilding from the ashes of the Holocaust, the teshuva movement, the economic development of Israel, the chessed infrastructure of the Jewish communities in America and Israel and elsewhere. The absorption of the Russian immigrants. Shiurim. Hatzolah. Daf Yomi. Joe Lieberman. Dark moments will be discussed too. The watershed events of 9/11, the Second Intifadeh. Maybe a nod to the 'shidduch crisis' and Rebbetzin Jungreis' heroic role in its solution.

But will Herald and Triumph give mention to tefillin dates and unmarried women going to the mikva? Will it discuss crises of faith, the Nosson Slifkin ban and near-schismatic issues such as metitzah be-peh and eruptions of bans on Indian hair wigs (come to think of it, will it discuss expensive wigs?) and bugs in the water and backlash and the gross materialism of Flatbush and Boro Park and the staggering burden of tuitions and the high cost of frum living and frum kids dropping out of yeshivas and dying of drug overdoses and the too many cases of rabbinic sexual abuse and the myriad other social ills that we face -- as all earlier generations did? Chances are he will not. Or at least the treatment will provide a generally very positive picture of the holy generation of early 21st century American and Israeli Jewry. Yes, if one knows how to read between lines one will catch glimpses of much of the dark side. But in general, this book of historia will enable its readers to pat themselves on the back and sigh when they think of the memory of us, their heilige bubbes and zeides.

Certainly books that give the warts and all will be written too. But there is no reason to believe that the good old Jewish hagiography we've come to know and love (or hate) will predictably come too.

There are basically two views of these historical distortion-by-way-of-omission literature. On the one hand, viewed from within, they are lamentable. As a frum Jew I do not feel that it is enough that I will read whatever literature I like and form, hopefully, a more realistic view of history regardless of what the hagiograpghies say. Even though there is a small minority that knows what happened and how it happened that is not enough. The nearly-Soviet version of How It Was is widespread. It is how we were taught, it is how our children are being taught. If history gives us a perspective with which to shape the present then those of us who are outraged when realistic depictions of personalities and events are distorted for polemical purposes are not just outraged at the depictions themselves, they are outraged for these falsehoods have real world implications.

On the other hand, such hagiographic literature is a realistic record of the values, hopes and longings of the communities which they serve. Whether or not we wish to change it, much can be learned about how these communities are rather than how we wish them to be.

It has been my observation that there is a growing awareness that the official literature is not the entire picture. It will be interesting to see what comes down the river.

Thalmvd exhibit at the YUM

Many other beautiful and important manuscripts and early printed editions are included in the exhibit. Of special interest are the Church edicts ordering the banning and burning of the Talmud and several texts that were censored by the Church Censor by means of writing over the offending words in black ink, through which the original text is still visible. One example to be seen is an Aggadah found early in Masechet Berachos that has the night divided into three mishmorot (watches), with God roaring like a lion as each mishmor passes from one to the next. Apparently the Church didn't appreciate the metaphor, for God's roars, kavyachol, are in frustration at what the non-Jews have done to Israel.

Of special interest is

Another noteworthy part of the exhibit was the continuously playing videos of Talmud study around the world, particularly the exceedingly rare video of bachurim learning be-chavrusa and gathered around a rebbe in Ponevezher Yeshiva in 1932. Of note is the way in which they were dressed to the nines, wearing gray hats and ties while in the Beis Midrash (to say nothing of their chupps atop their head). I noticed that one bachur's hat was very shabby and faded, which would indicate something about their level of poverty. Still, the dedication to presenting yeshiva students as people of dignity is evident. The excitement and interest of the group of students gathered around their rebbe, a kindly and pleasant looking man is intriguing.

What was especially intriguing for me is that to look at these young men in 1932 is to look at myself not too long ago. Their faces and mannerisms are eerily familiar. Those of them who may not have been murdered by the Nazis would be over 90, if still alive, today. But they are forever frozen in time in film, 20 year old yeshiva bochurim engaged in the pursuit of countless young Jewish men past, present and future.

More on the Ani Ma'amins

A lot of ink has been splashed about on the Rambam's 13 Principles. Here's a little bit more.

If one thinks about what he didn't include in his list one may come up with things; for example, why isn't belief in am ha-nivchar (Jewish chosenness) a principle? Ikkarei emunah are roots of Judaism; evidently the Rambam did not believe that chosenness was one. The question becomes more acute, I believe, if you accept Marc B. Shapiro's premise in The Limits of Orthodox Theology* that the Rambam's listing of principles are more a matter of what he thought were necessary beliefs** as opposed to [entirely] true beliefs**. If that were the case then the question of why Jewish chosenness would not be a necessary belief is especially noteworthy insofar as it is certainly a fundamental Jewish belief of some sort.

To put it another way, if we assume that according to the Rambam if any one of his ikkarim were to be discarded by the the Jewish people then no less than a pillar of Judaism would be uprooted why is it that am ha-nivchar is not one of them? Could it be that according to the Rambam belief in Jewish chosenness is not necessary for Jewish people? Evidently that is so.

It seems odd. At least it strikes me as odd. Maybe the reason he did not include it is because the supercessionist assertion of Christianity and Islam towards Judaism were perceived by Jews as arrogant and unfounded and only reinforced their own belief in Jewish chosenness.

Thoughts, anyone? Also feel free to share if you can think of an other concept that may have/ should have been given as an ikkar.

*Which does not, by the way, take issue with the factual truth of any of the Rambam's principles, only the assumption that they were universally received by all earlier and subsequent rabbinic authorities.

**A necessary truth would be telling children that crime doesn't pay, even though there is quite a bit of evidence to the contrary.