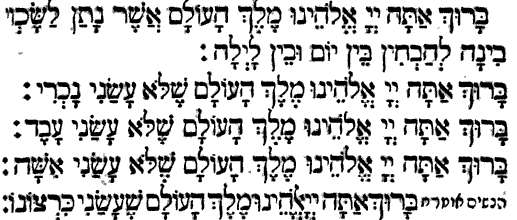

Her first major culture shock came when reading the translation of the Mishnah Peah 1:1, the אלו דברים שאין להם שעור, which forms part of the beginning of the service. Amazingly we can know exactly which edition of the siddur this congregation was using, because she includes the translation which offended her; "the appearance of every male", and this being a non-literal translation of הריאיון it was an easy matter to find the siddur. It was Tefilat Yisrael - Prayers of Israel (originally published in 5609; the edition I linked to is the fifth, from 1854). As you can also see, she didn't seem to have any idea what was meant by "commandments" in this text. Actually, I wouldn't be surprised if a good many worshipers didn't really understand it either:

The next part of her cultural shock and distaste appears to be from memory rather than an actual text (unless I am mistaken about my identification of the siddur). She has no problem thanking God for not making her a heathen, but was quite surprised at the blessing Shelo asani ishah. She looked "at the numbers of elegant, refined women" who looked on as the men recited it, and the alternative blessing for women was announced. At this point it is interesting to note that in her description it is a "handful" of men who said the blessing, and the formula "and the women shall say" is heard by the women. This is not a very active audience participation service. Calypso also notes the organ being played.

"She-lo asani nochri"? How common is this?

ReplyDeleteIt's not common today, but it was a fairly common German nusach at the time. See, for example, pg. 5 in this Heidenheim machzor (link).

ReplyDeleteThe Chief Rabbi's siddur (the English one, not the Koren siddur) has it too, so I guess it's minhag Anglia as well.

ReplyDeleteIt's replacing rabbinic Hebrew with Biblical. The guy who used to say it in my shul also said "B'safa brura u'vniema kedosha, kulam..."

ReplyDeleteSurprising that the offending line was not already removed by the congregation, which ostensibly was following a Reform liturgy.

ReplyDeleteThis was 50 years before women won the right the vote. What makes you so sure that a Reform congregation would find shelo asani isha offensive?

ReplyDeleteOf course it is somewhat of a chiddush that they were using an Orthodox siddur, but that could have been a financial consideration. Also, Reform took many flavors, especially in the United States. Many American Reform congregations were Orthodox in all respects except for the organ and lack of mechitza.

True enough. In my mind, though, I connect the lack of mechitza to a sense of egilitarianism, and the desire to borrow from the aesthetics and modern sensibilities of the non-Jewish faithful.

ReplyDeleteTo wit, this refined, spiritual woman seemed to take offense at the apparent slight to her gender, and thought it bothersome enough to report it to all and sundry.

I wonder what influenced the deletion of the traditional bracha -- suffrage, the growing Hebrew literacy of woman, or cultural norms? My uneducated guess is all three.