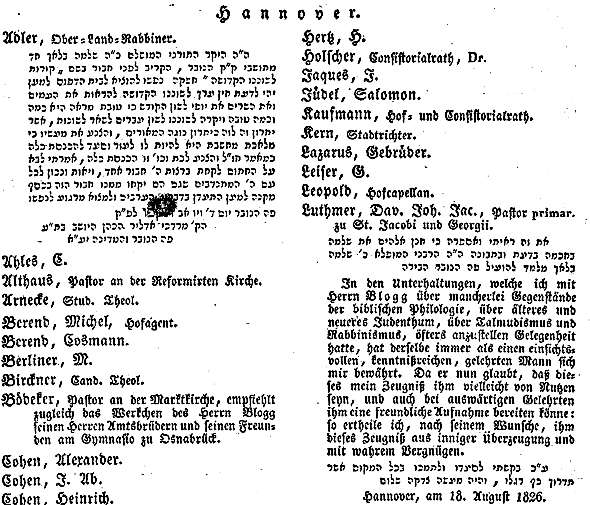

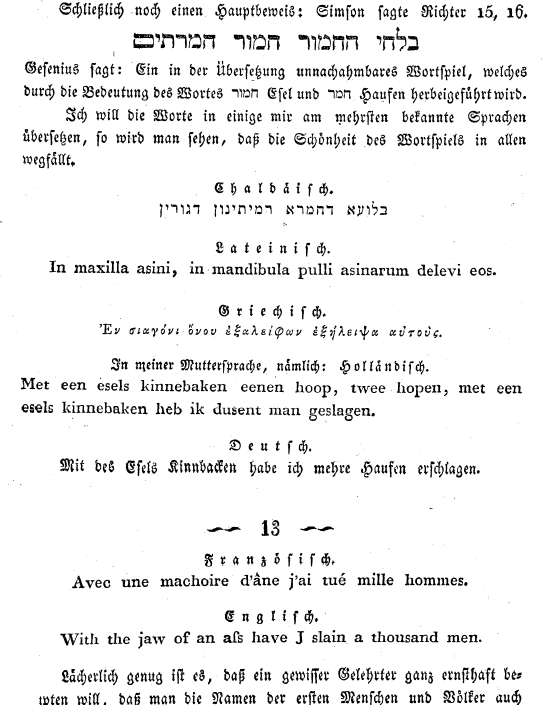

Earlier I had quoted two versions. One deals with the color of Rashi's shirt, and the other with the brand of tobacco he smoked (and I playfully noted that the answer could only be none, since tobacco is an American crop and was unknown in Europe until 400 years after Rashi lived). Read the first post for the quotes, or the appendix at the very end where I include many versions.

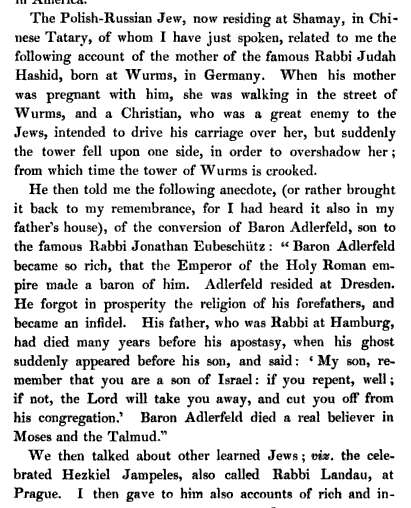

I am particularly interested in the attribution of the saying to Rabbi Jacob Ettlinger (1798-1871). Rabbi Aharon Rakeffet-Rothkoff (nee Arnold Rothkoff) paraphrased the saying twice. The first was in his 1967 doctoral dissertation Vision and Realization: Bernard Revel and His Era; the second was in the book version, 1972's Bernard Revel: Builder of American Jewish orthodoxy. There is slight difference in language. Evidently the second version, quoted in the other posts, was a result of language beautification for its publication in book form. But these differences don't matter, as both are a paraphrase and convey the identical impression. But more importantly, only in the dissertation is his source for the statement given:

That is, he heard it in BMG, the Lakewood Yeshiva, in 1955. It is one of those things "they say," an oral tradition.

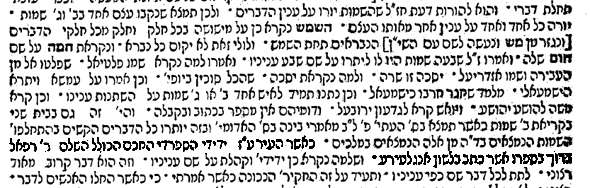

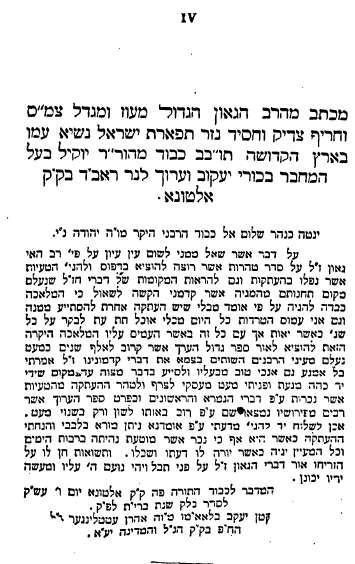

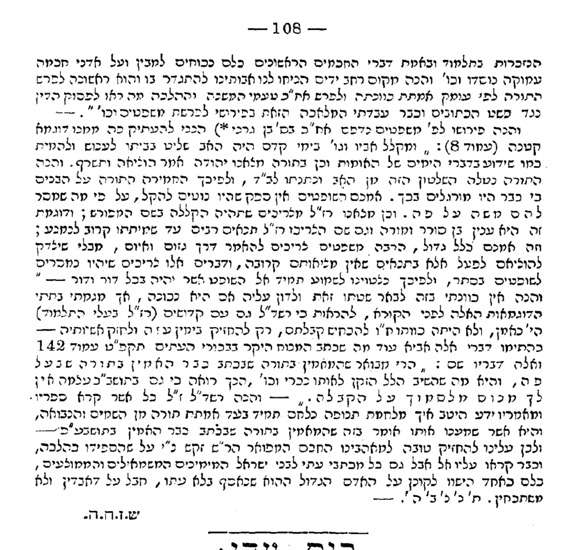

It isn't mentioned at all in Dr. Judith Bleich's 1974 dissertation Jacob Ettlinger , His Life and Works: The Emergence of Modern Orthodoxy in Germany. This doesn't mean that it's not an authentic oral tradition. Perhaps it was too folksy for her to mention, or maybe she just hadn't heard it. She never learned in Lakewood, after all. Still, one would assume that if it is an authentic quote than at least an echo of it would be found in her discussion of R. Ettlinger's periodical the Der Treue Zionwachter with its Hebrew supplement the שומר ציון הנאמן, for this periodical was founded because the German periodical literature of the time was published by Reformers, and contained polemical material in both its German and Hebrew pages. Although the traditional scholarship published in its pages was clearly an implicit criticism of the Wissenschaft work of Zunz and the like, the sort of attitude expressed by the quip we're discussing was apparently not found in its pages. Apparently what shirt Rashi wore or what tobacco he smoked had nothing to do with Reform. In fact, Bleich notes (pp. 7-75) that R. Ettlinger himself was involved in "the scientific study of texts and in the scholarly research of his time." He played a leading role in the printing of unpublished texts, and was interested in establishing correct and accurate texts, c.f., the introduction to Aruch La-ner on Niddah where he expressed amazement that some rabbis neglected such matters:

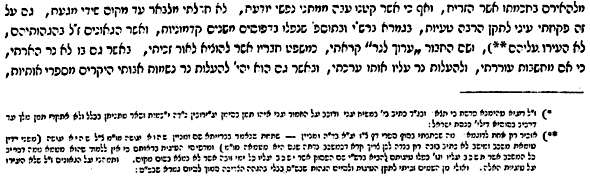

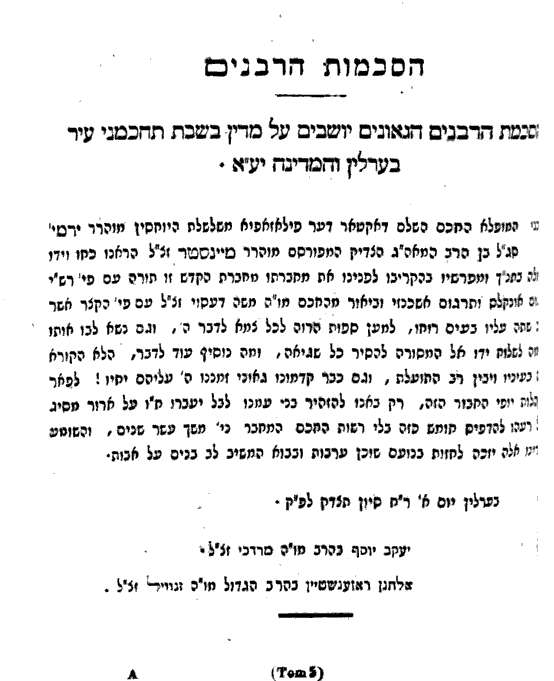

She further notes that Responsum #60 in Binyan Zion attempts at length to verify the authenticity of a recently published volume of responsa attributed to Rashi, concluding that the first twelve were indeed written by Rashi, while the rest were actually written to Rashi by one of his teachers. In addition, he reiterated the importance he attached to textual accuracy in the haskamah he wrote for the work of Rabbinowicz, included at the beginning of the first volume of Dikduke Soferim:

In 1856 a commentary of Rabbi Hai Gaon on Taharot was published (link), and it contained corrections and notes from R. Ettlinger (although he writes that he will only call attention to errors with written support for an emendation, but he will not give conjectural emendations).

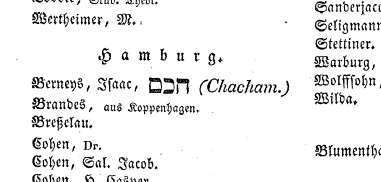

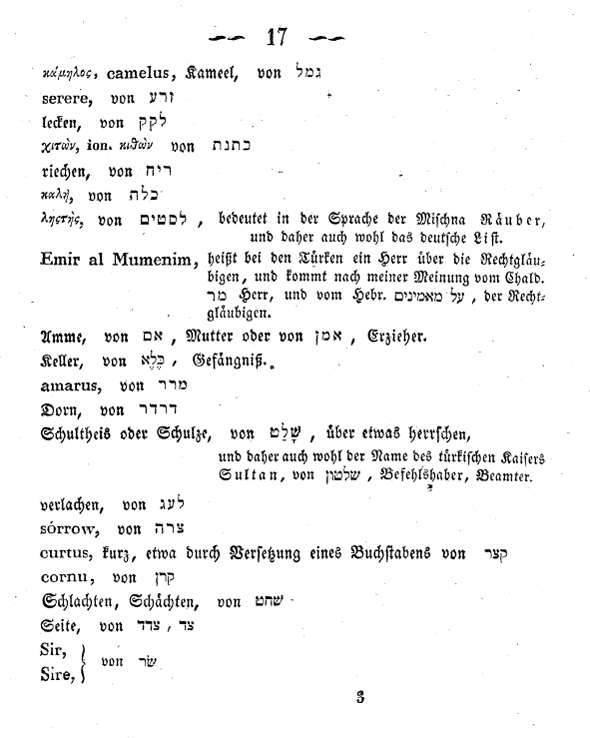

In addition, he himself published many manuscripts in שומר ציון הנאמן. The periodical also included many other articles of a scholarly, textual character. For example, it featured analytical articles on the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, Biblical commentaries like updates to R. Mecklenburg's Ha-kesav ve-ha-Kabbalah (included in its 2nd edition) and liturgical topics, as well as publications of materials found in the Hamburg Library. In addition, the magazine promoted the study of Hebrew and published Hebrew belles lettres. An article on dikduk by Salmon Dubno appeared in its pages.

This means that he was involved in critical scholarship at a very high level. But all of this, of course, does not actually show in any way that he related to Wissenschaft des Judentums or would not have been critical of Zunz and his work. The scholarly approach and publications he was involved in surely were a departure from the usual kind of traditional scholarship (to which in fact Jewish Wissenschaft arose partly in opposition), but they are certainly not solely an invention of the 19th century (while they are very characteristic of the time). In fact, it has been pointed out by Mordechai Breuer (Modernity Within Tradition) and doubtlessly by others that there was a sort of Ashkenazic quasi-tradition of critical textual scholarship of this kind. He lists 18th century luminaries like Rabbi David Frankel and R. Isaiah Berlin Pick, as well as grammarians like Wolf Heidenheim, and the scholarly production of Yehoseph Schwarz. Such a critical tradition existed, although it ran against the currents of the mainstream and, I might, add we should bear in mind that 19th century examplars of this approach like R. Ettlinger and Yehoseph Schwarz were university educated.

In fact one could almost make the (speculative) case that it actually supports the notion that this was Rabbi Ettlinger's sentiment, since in fact Zunz's style actually was to largely clarify historical matters relating to and about Rashi and other figures rather than to explicate their words. He was a historian, not a commentator. For example, Zunz wrote a justly famous article clarifying the matter of Rashi's name, the history of "Jarchi" and so forth. Although we can justly describe R. Ettlinger as having a critical historical sense and incorporating it into his scholarship, he was certainly a traditional Torah scholar and not a historian of Jewish literature, like Zunz.

I would be remiss here if I did not mention R. Ettlinger's haskamah to Wessely's commentary on Bereshis, published by his son Salomon Naphtali Wessely in Hamburg in1842, with the title of עוללות נפתלי. Unfortunately I can no longer supply a link to this fine commentary approved of by great gedolim of unimpeachable reputation because this book was purged this very week from you-know-where.

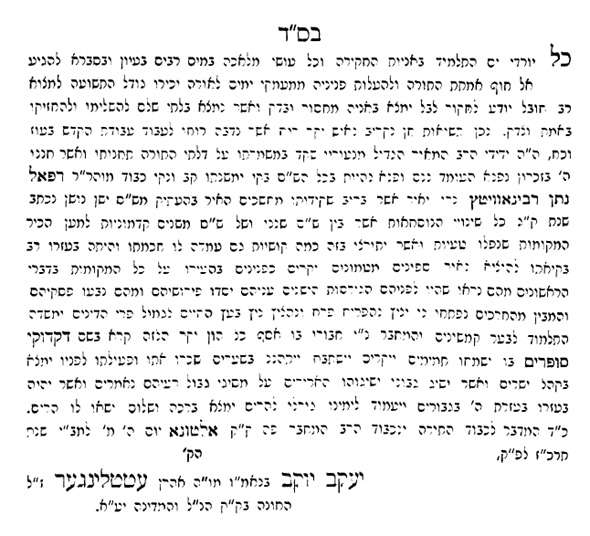

Here is the approbation:

Incidentally, the genesis of Wessely's commentary (no pun intended) lay in a period in 1778 when he was out of work after his employer liquidated the business without bothering to help him find other work. Friends set up public lectures for him two or three times a week as a source of income. His topic was the first chapters of Genesis. Sadly the lecture series which had garnered an overwhelming response in the beginning gradually dwindled, it is surmised, because his approach was traditional and didn't deal with modern (ie, 18th century) Bible scholarship.

Since we're on the topic, in the pages of the aforementioned שומר ציון הנאמן, the rabbi of Wuerzburg, Rabbi Seligmann Baer Bamberger, wrote the following:

(Of course this is a composite image; my intention is simply to show the beginning of his piece with how he refers to Wessely with זללה"ה. I would think he was headed for the other place if he was so bad that his books are worthy of purging. If you wish to locate the entire article, it is in the 27 Kislev 1848 issue #65 pp. 130-1.)

Here seems like a good place to post the Wuerzburger rabbi's criticism of Samuel David Luzzatto (Halevanon #2.22 1865). The background is that Shadal died, and the Levanon featured words of eulogy in several issues by Senior Sachs which depicted him as a great gaon and tzaddik. Rabbi Bamberger was of the opinion that he was neither of these, but a heretic. So in the interest of truth he felt obligated to reply and noted 7 examples of things that were totally unacceptable in his abbreviated Torah commentary Hamishtadel (Vienna, 1847). Please note, the link is to the book version of Hamishtadel. It was first printed as an appendix to the Vienna edition of Mendelssohn's Biur, and this is the version that R. Seligmann Baer Bamberger actually refers to.

An example of what he was objecting to, and then his letter:

Incidentally, I think it's fair to say that he wrote with restraint, and one cannot but agree that he was sincerely motivated to speak the truth as he saw it. In my opinion this is a model for how a rabbi should speak up against views he feels are contrary to the tradition. Nowhere does he cry צא טמא or call anyone an אפיקורוס. In fact he says that he's speaking out only so that no one should say that the rabbis' silence [in a matter like this] indicates assent.

Shadal did not go undefended, for the next issue featured a response by S.J. Halberstamm:

It's worth noting that HaLevanon was what would we today call a Chareidi paper. In fact, today's Chareidim recall it as just that. Can anyone imagine such writers and such an exchange in today's Chareidi press?

Once we're on the topic, why leave it just yet?

Some months ago the עלים לתרופה, a Belzer parsha sheet widely distributed in Israel, Europe and the United States included in its biographical column יומא דנשמתא a biography of my favorite Victorian rabbi, הגאון הצדיק רבי נתן הכהן אדלר זצ"ל רב הקולל של לונדון-בעל נתינה לגר, Nathan Marcus Adler. His piety and scholarship should of course remain unquestioned (even if Rabbi Adler "pleads guilty to an occasional novel" [link]).

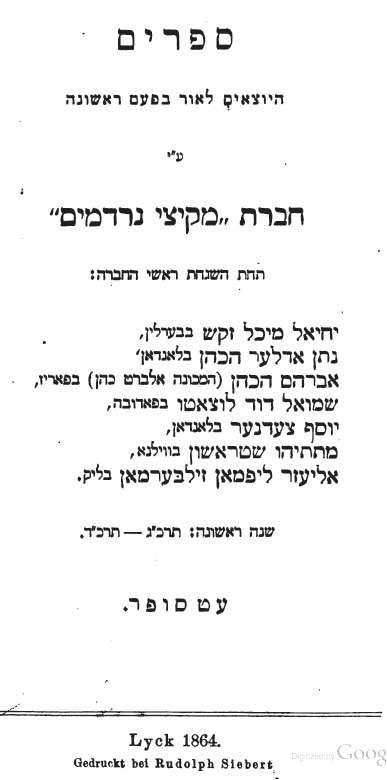

The article quotes Rabbi Adler that the Targum Onkelos was written by the proselyte "with wisdom, according to tradition, etc. . . but not like the view of some scholars who are of the view that the Targum was written for the plain people, and not the scholars. Actually it was written for all the people, plain and scholars alike . . ." This opinion is supported and demonstrated by Rabbi Adler in his commentary. The footnote in עלים לתרופה (correctly) notes that the opinion he meant to counter was Samuel David Luzzatto's in his Ohev Ger (Vienna 1830) that the Targum's primary audience was the plain people (הדיוטות) and not the scholars. Various consequences follow from the respective opinions. But the footnote must write a little editorial appelation which I am confident that Rabbi Adler would have been quite upset to read: בכך יצא חוצץ נגד המשכיל האיטלקי שד"ל שר"י שחיבר ביור משלו על תרגום אונקלוס בשם אוהב גר בו פוער פה כאילו התרגום נועד לפשוטי העם. The idea is presented here as if it's some grievous outrage, as opposed to a carefully reasoned scholarly hypothesis. Furthermore, Rabbi Adler's view is framed as a response to a grievous outrage, rather than a gentleman's disagreement on scholarly grounds. In fact Rabbi Adler had nothing but respect for Shadal. They were colleagues on the board of the Mekize Nirdamim Society:

It is difficult to see why he would sit on a board with a רשע, to publish seforim no less.

He refers perfectly respectfully to him many times in Nesinah Lager. In addition, he also published the Patshegen - Sefer Yaer commentary which had belonged to Shadal in the very volumes of the pentateuch which contained Nesina Lager. For example, in the introduction to the Patshegen he calls him החכם הגדול ר' שמואל דוד לוצאטו, nary a שר"י in sight:

This is not to say that if you think highly of someone you therefore accept every opinion they ever held. I am not taking this weekly Torah sheet to task for failing to agree with him in the totality of every detail he ever thought or spoke. However, I think it is a bit over the top to be so out of touch about the kind of person given the הגאון הצדיק treatment here. Sure, there is plenty of material where this image is drawn from in the person of the real Rabbi Adler. But a complete picture is lacking, and one wonders if הגאון הצדיק can survive the complete picture.

To fill in some more details of the complete picture:

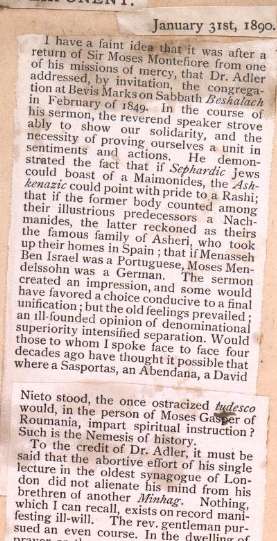

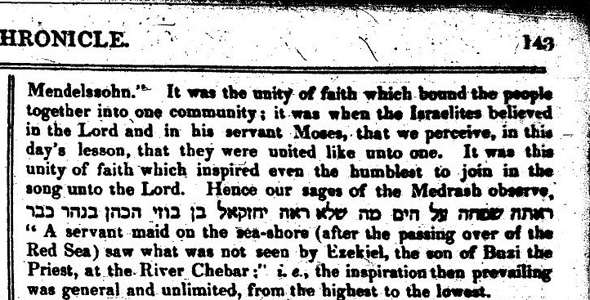

On January 31, 1890 The Jewish Exponent printed the text of a shabbos derasha delivered by celebrated American rabbi Sabato Morais in tribute to "The Late Chief Rabbi Dr. N. M. Adler." Morais had himself spent many years in England. He related that at the time British Jewry was experiencing a painful schism, occasioned by reformers and cherems. This occurred in 1840. Some ("who had witnessed with deep sorrow the schism" "which deprived both the Ashkenazim and Sephardim of some of their most valuable members") had hoped that when Rabbi Adler was brought in to assume his post in 1845 that he could effect a reconciliation. This did not happen, as the acrimony was then very deep. Morais recalled that he himself was rebuked because he wrote a Hebrew elegy for "a Mr. Hananel de Castro," one "who had tried in vain to pacify angry spirits," such was the bitter feelings. Still, Rabbi Adler did reach out to the then rabbi-less Bevis Marks Synagogue of the Portuguese Sephardim, in an address delivered there on Parashas Beshalach in February of 1849. The purpose of this speech was to show that there was common ground and could be solidarity between the two communities:

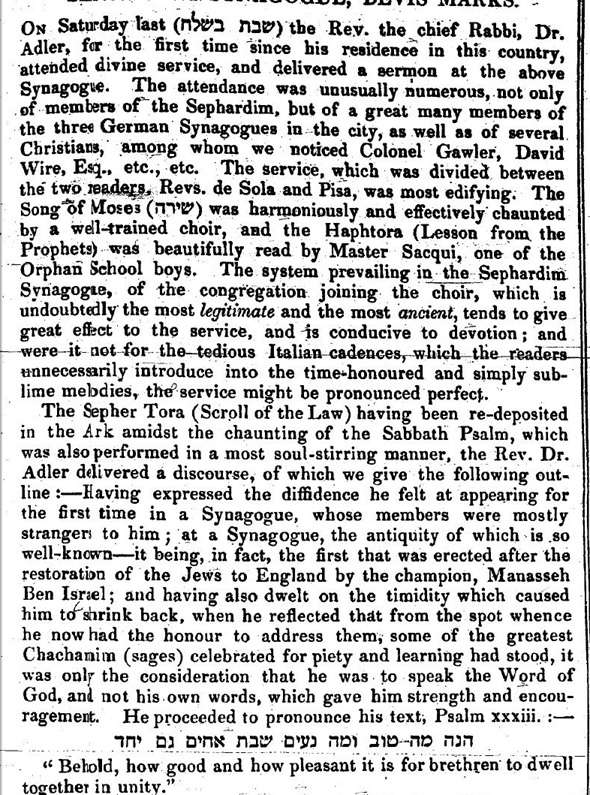

That is, to show how the Ashkenazim and Sephardim are really brothers, he gave a laundry list of "You Sefardim have this, and we Ashkenazim have that." Listing luminaries, he orated that Sephardim had Maimonides, but Ashkenazim had Rashi. Ramban was Sepharadi, the Rosh was Ashkenazi. Menasseh ben Israel was Portuguese, and Mendelssohn was German.

In case anyone suspects that this is the faulty memory of a man writing 40 years later, below is how the sermon was recorded in the Jewish Chronicle in February of 1849:

So there you have it: הגאון הצדיק רבי נתן הכהן אדלר זצ"ל felt comfortable putting Rashi, the Rambam, R. Menashe ben Yisrael and Moses Mendelssohn in the same paragraph (it's unclear if he also mentioned the Ramban and the Rosh as Morais mentioned).

Getting back to what brand of tobacco Rashi smoked, I began with noting that the attribution of the quip to Rabbi Ettlinger was a remark that Rabbi Rakeffet heard in Lakewood in 1955.

In 1903 Gotthard Deutsch wrote an article about Solomon Munk on the occasion of the Centenary of his birth in the Yearbook of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. Deutsch excoriates Graetz's inability to "conceive a character in its historic setting," for which reason he wrote so bitterly about so many people. For example, he called David Friedlander a "Flachkopf," Mendelssohn's ape. Deutsch writes that Friedlander was not so bad, he just saw that the Judaism taught by contemporary rabbis like the Noda Beyehuda and Rabbi Raphal Kohen of Hamburg "could not survive in a cultured atmosphere," and this is the explanation for much of his venom. Friedlaender must be viewed in the contaxt of his time, and this explains some of his lack of temperance. Deutsch happens to be correct about Graetz generally, in my opinion.

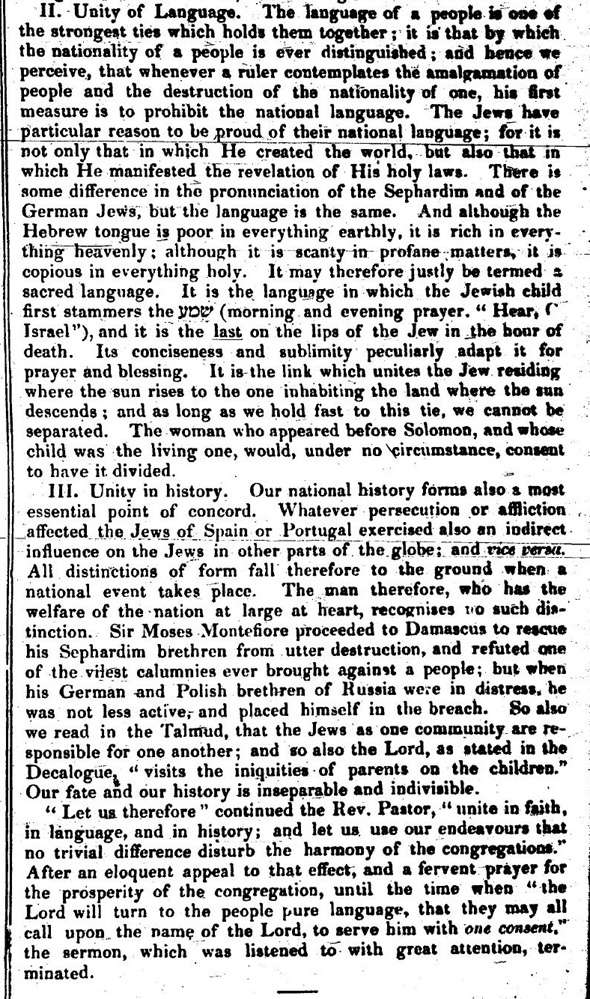

Apparently Friedlander criticized someone who desired his son to have a secular and Talmudic education. Friedlander thought such a thing was ridiculous and impossible. Deutsch is of the opinion that no one back then had such a vision:

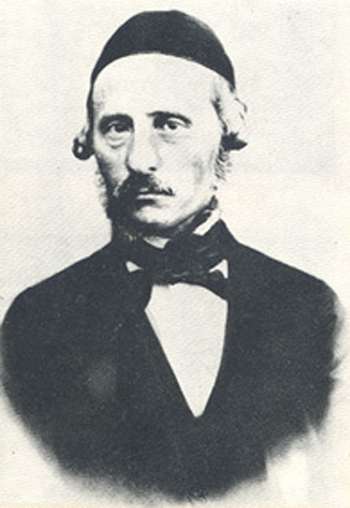

Of course Jacob Joseph Oettinger looks like Jacob Ettlinger - even the peculiar orthography can be explained (see here for some discussion about Ettlinger's surname) - but in fact they were two entirely separate people (even aside for the fact that the author of the Aruch Laner whom we have been discussing was named Yaakov Yukev, and not Yaakov Yosef). Rabbi Oettinger (1780-1860) was the last Chief Rabbi of Berlin (having taken the post in 1820). Here is what he looked like in 1840:

He was, for Germany at the time, a throwback to the past, a representative of what came to be seen as the Alt-orthodoxie, the kind of rabbi who could barely speak German (this in contrast with rabbis like Isaac Bernays, Samson Raphael Hirsch and others who would typify what came to be known as Neo Orthodoxy).

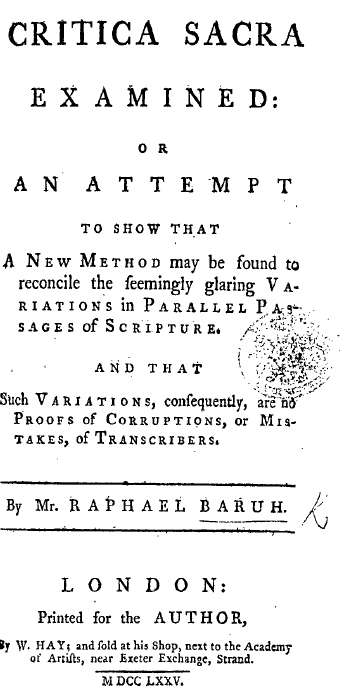

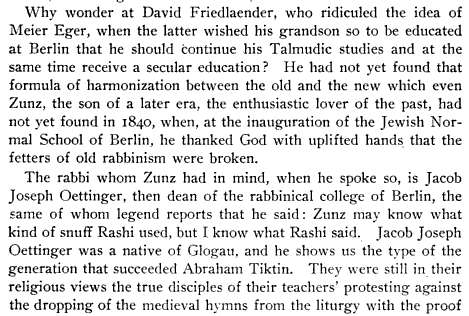

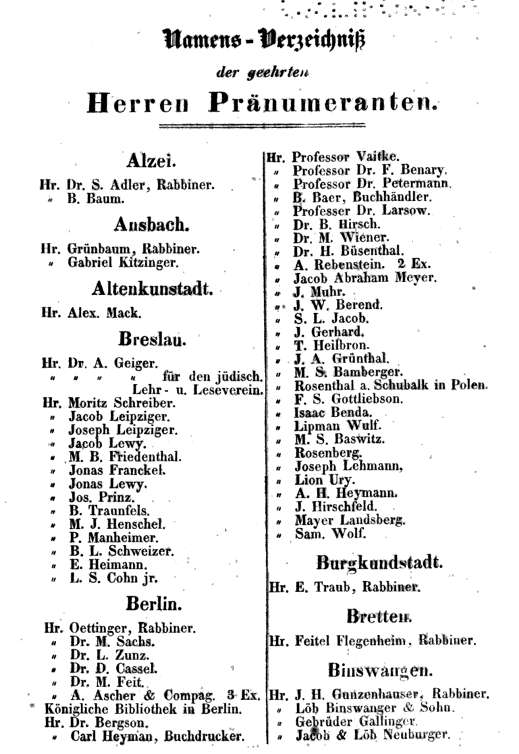

I could well imagine Rabbi Oettinger being shown a copy of Zunz's pioneering 1823 article about Rashi, Salomon ben Isak, Genannt Raschi in the first issue of the Zeitschrift für die Wissenschaft des Judenthums or even its 1840 Hebrew translation. Perhaps he was told that this is an impressive example of the new Jewish scholarship. After reading it one can imagine him saying "Zunz may know what brand of tobacco Rashi smoked, but I know what he said." But that's speculative, and besides, Rabbi Oettinger knew perfectly well who Leopold Zunz was, both living in Berlin. Below is a subscription sheet to an 1848 edition of Ibn Kaspi's commentary on the Moreh Nevukhim. Their names are in the column of Berlin subscribers:

But most importantly, Rabbi Oettinger was an actual opponent of Zunz. In 1834 he opposed the appointment of Zunz as rabbi of Darmstadt. He sent a letter to the community which was at least partly responsible for his not being hired:

Thus we have the most likely explanation for why Judith Bleich doesn't mention the tobacco/ shirt color quip in her dissertation about Rabbi Ettlinger. This is a case of mistaken identity. We might add our own aphorism about the Lakewood Yeshiva: "On the Main Line may know the difference between Oettinger and Ettlinger, but we know what the Aruch Laner says."

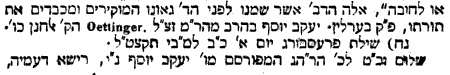

Incidentally, Rabbi Oettinger wrote a haskamah for the 5th volume of Dr. Jeremiah Heinemann's Chumash Mekor Chaim, that is, his edition of Mendelssohn's Chumash with Beur (link). This edition is probably most notable today because Rabbi Akiva Eger was a subscriber and maskim to the second volume, which is interesting because 'traditionally' it is the third volume - Wessely's Vayikra - that is kind of, sort of okay, and maybe the first volume - Salomon Dubno's Bereshis - but the second is mostly the production of Mendelssohn himself. Unfortunately this volume has not yet been digitized so I don't have the pictures to show Rabbi Akiva Eger's haskama and his name among the subscribers. However, here is R. Oettinger's approbation (co-signed with his junior co-rabbi on the Berlin Bet Din):

As an aside, Rabbi Oettinger's story furnishes some interesting facts. Whether or not the language he spoke should be called "Yiddish," it was the old German Jewish dialect (which was spoken by the vast majority of German Jews in 1780 when he was born), and definitely was not the German spoken by modern rabbis mid-century, Reform and Orthodox alike. It is told that people used to come to his sermons in the Great Synagogue of Berlin to laugh at the way he spoke. After 1845 there were three rabbis in Berlin, Rabbis Oettinger, Michael Sachs (1808-1860) and the aforementioned Elchanan Rosenstein. Rabbi Oettinger still spoke Yiddish, Rabbi Sachs spoke flawless German. Rabbi Rosenstein, it is said, aspired to speak High German but couldn't quite manage it, lapsing back into Yiddish. A joke popular at the time was "Dr. Sachs sagt; Reb Jeinkef Jossef sohgt; bei Reb Chone is nischt gesagt und nischt gesohgt."

That from Aron Hirsch Heymann's Lebenserinnerungen (1909). The same Heymann (1803-1880) - a major figure in Berlin Orthodoxy - describes the linguistic shift German Jews were undergoing in his childhood. He noted that the children didn't speak like their parents, but they also didn't speak like the Christians. Strangely, in certain respects they spoke more correctlly that the Christian children. He writes that the jewish children said "ja" (yes), the Christian children said "jo" and the Jewish parents said "jau."

The fact that Rabbi Oettinger did not speak German well did not, of course, mean that he never tried. The Jewish Encylopedia discusses reforms in the 1820s, and points out what I suspect is not widely realized today: religious reforms were not encouraged by the government (at least not in Prussia). Like most conservative autocratic governments, it supported the status quo, not religious ferment and what could conceivably devolve into revolutionary activity. Thus, it did not approve of Jewish reforms, and oftentimes anything that even seemed slightly reformist was deemed illegal. Discussing how German sermons were forbidden, the JE writes: "This regulation was so strictly carried out that when Rabbi Oettinger, at the dedication of the new cemetery in 1827, delivered an address in German, the police saw therein a forbidden innovation."

Steven Lowenstein, in an article in the LBIY called Two Silent Minorities, Orthodox Jews and Poor Jews in Berlin 1770-1823, notes that lack of observance was so rampant in Berlin in the 1820s that Rabbi Oettlinger used to leave weddings early, before the food was served, so as not to cause insult to those whose weddings which were not kosher.

There's probably a lot that can be said about his relationship with Michael Sachs, a former student and the aforementioned Berlin rabbi who preached in perfect High German (and a famous Wissenschafter whom Breuer counts as another Orthodox example of Germany's tradition of critical scholarship), but I'll leave that and other issues for now.

Finally, here is Rabbi Oettinger's signature in letter concerning the Alexandersohn affair, which also awaits another post. I admit that I didn't look closely and initially thought this was Rabbi Jacob Ettlinger!

Appendix: Various Versions of the Rashi Quip

1. "There was an interesting anecdote, about 150 years ago, when the Rabbinical Seminary in Breslau was founded and the news reached a very famous Rabbi, Rabbi Moshe Sofer, the Chatam Sofer as he is called. They told him about this new seminary where they were studying Rashi. He answered, "If you want to know what color shoelaces Rashi wore, you should go to that seminary, but if you want to know what Rashi really said, you have to come to the world of Yeshivos, to learn the text itself."

Manfred Lehmann "Rashi as grammarian and lexicographer" pg 437 in Rashi, 1040-1990: hommage à Ephraim E. Urbach ed. Gabrielle Sed-Rajna, 1993.

2. "The Rabbi entertains a certain contempt for the historian - who explains away rather than reconciles, and who is, evidently lacking in depth and subtlety. Said the celebrated Akiva Eger (at the end of the eighteenth century), "If you wish to know what kind of clothing Rashi wore, by all means ask Geiger. If you want to know what Rashi said and thought, ask me!"

Gerald Abrahams "The Jewish Mind" pg. 112, 1962.

3. [Wolfoshn's self-description as a "non-observant orthodox Jew] is not this rigid orthodoxy we find in Jacob Ettlinger;s famous dictum from the begin[ning - sic] of the 19th century; "If you want to know which tobacco Rashi smoked, ask Zunz. If you want to know what Rashi wrote, ask me."

Martin Ritter, "Scholarship as a Priestly Craft: Harry A. Wolfson on Tradition in a Secular Age" pg 454 in Jewish Studies Between the Disciplines (Judaistik Zwischen Den Disziplinen) : Papers in Honor of Peter Schafer on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday.

4. "In the words of Rabbi Dr. Ezriel Hildesheimer, the Rector of the great Orthodox Rabbinical Seminary of Berlin, "Jews are more interested in knowing what Rashi has to teach us than in knowing what were the color of the clothes Rashi wore."

Berel Wein, "Triumph of Survival: The Story of the Jews in the Modern Era 1650-1995" - Page 56.

5. "Zunz knows all the details of Rashi's life, what he did and where he lived and traveled; but I know what Rashi said and wrote."

Joseph L. Baron, "A Treasury of Jewish Quotations" page 438, 1962.

6. Even Salo Baron quotes it, again, I could not see his source, so please tell me if you have this book:"The reputed asssertion of an old-type rabbinic critic of Leopold Zunz's significant biography of Rashi that "if you want to learn when Rashi sneezed, you read Zunz, but if you desire to understand what Rashi really said, you better come to me!" was not completely unreasonable. If you desire to understand what Rashi really said, you better come to me!"

Salo Baron, "The contemporary relevance of history: a study in approaches and methods," - page 62, 1986.

****

There is little doubt in my mind that I will trace this quip further, and I am also expecting some good contributions in the comments, so stay tuned for a follow up.