Friday, December 30, 2011

A primitive guide to safrut from Boston, 1763.

Here's a great page in Stephen Sewall's 1763 Hebrew Grammar (patterned, according to the subtitle, on Mr. Israel Lyons' Hebrew grammar). It attempts to teach the rudiments of Hebrew writing, even giving instruction for the best way to cut the pen nib.

Thursday, December 29, 2011

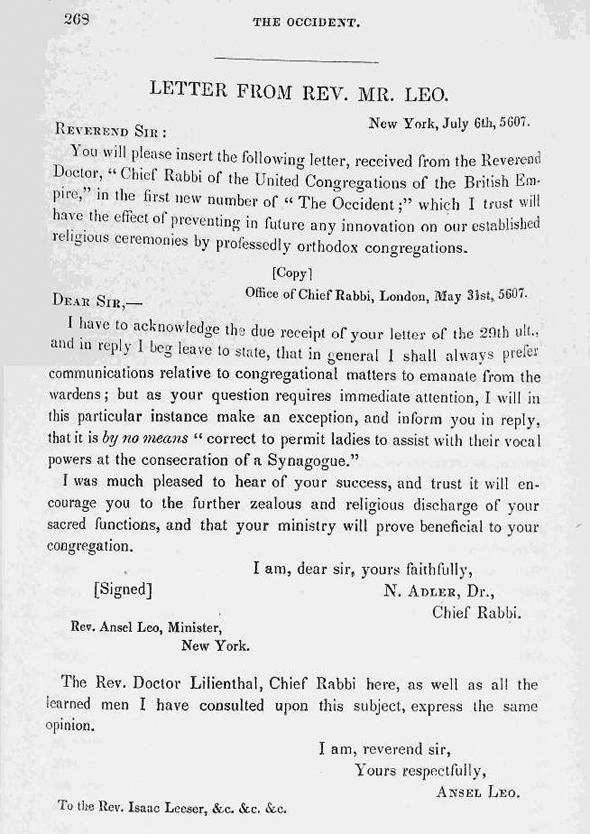

A responsum on "ladies assisting with their vocal powers" from 1847.

Here's an interesting letter from London Chief Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler printed in the Occident in August 1847, concerning whether or not it is "correct to permit ladies to assist with their vocal powers at the consecration of a Synagogue":

The questioner, the Rev. Ansel Leo (1806-78), was a chazzan in New York's Bnai Jeshurun (aka Elm Street Synagogue). He refers to R. Max Lilienthal as "Chief Rabbi here," because he had been appointed rabbi of a United German" kehilla in 1845.

This was picked up by quite a few newspapers across the country. Here is a mention of it in the New Jerusalem Magazine, 1848:

The questioner, the Rev. Ansel Leo (1806-78), was a chazzan in New York's Bnai Jeshurun (aka Elm Street Synagogue). He refers to R. Max Lilienthal as "Chief Rabbi here," because he had been appointed rabbi of a United German" kehilla in 1845.

This was picked up by quite a few newspapers across the country. Here is a mention of it in the New Jerusalem Magazine, 1848:

A review of a review of a review

There seems to be a hierarchy in printed matter. Books are more permanent than journals, and journals are less ephemeral than newspapers. And comic books are at the top, at least if their wise owners kept them in mylar since the 1930s, and Batman is doing the Charleston with Groucho Marx on the cover.

One of the most interesting things about books and even journals are the reviews. Because they are often published in the most ephemeral format sometimes they get lost. Oh, there was and is Microfiche, and sometimes libraries even have the physical copies. But it's safe to say that more people have read the 2nd issue of the Jewish Quarterly Review than the review of it printed in London's Jewish Standard on May 31, 1889.

So here is an excerpt from said review. The piece I post concerns Isidore Harris's (still) excellent article series "On the Rise and Development of the Massorah." The writer makes some interesting points and, most interestingly (this is 1889!), also rejects R. Elias Levita's groundbreaking position that the accents and vowels are post-Talmudic.

Another interesting thing is his mention of Claude Montefiore's essay on Purim. He writes that "Mr. Montefiore should not be always riding his hobby [horse] that the Book of Esther is not based on historical evidence. The feast of Purim kept from generation to generation furnishes sufficient evidence to that book, besides the internal detailed and clear evidence of places, names and date. It is, therefore, unjust to believe in Greek and Roman books and statements, and to disbelieve our canonical Jewish Book of Esther.

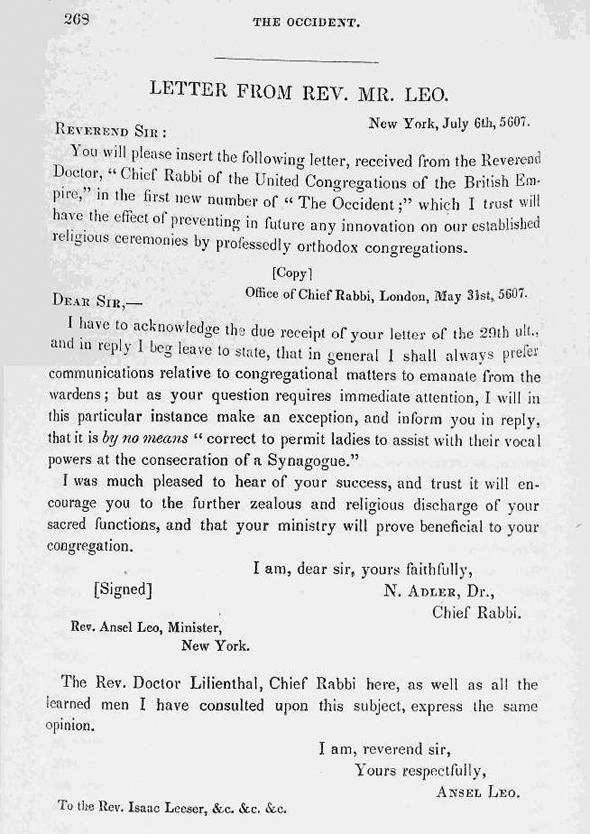

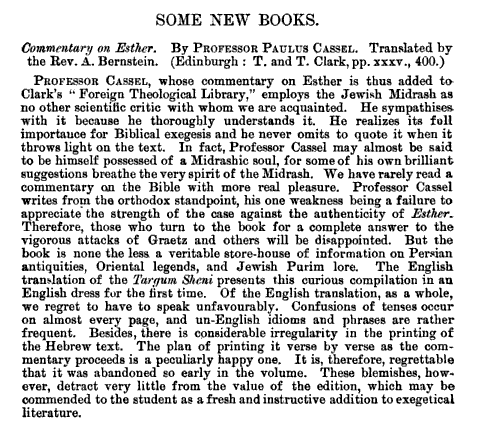

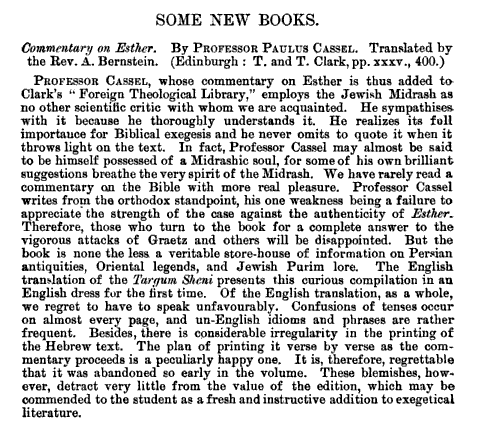

Here is Montefiore's review, to which he refers. Paulus Cassel, born Selig, was the convert brother of David Cassel:

One of the most interesting things about books and even journals are the reviews. Because they are often published in the most ephemeral format sometimes they get lost. Oh, there was and is Microfiche, and sometimes libraries even have the physical copies. But it's safe to say that more people have read the 2nd issue of the Jewish Quarterly Review than the review of it printed in London's Jewish Standard on May 31, 1889.

So here is an excerpt from said review. The piece I post concerns Isidore Harris's (still) excellent article series "On the Rise and Development of the Massorah." The writer makes some interesting points and, most interestingly (this is 1889!), also rejects R. Elias Levita's groundbreaking position that the accents and vowels are post-Talmudic.

Another interesting thing is his mention of Claude Montefiore's essay on Purim. He writes that "Mr. Montefiore should not be always riding his hobby [horse] that the Book of Esther is not based on historical evidence. The feast of Purim kept from generation to generation furnishes sufficient evidence to that book, besides the internal detailed and clear evidence of places, names and date. It is, therefore, unjust to believe in Greek and Roman books and statements, and to disbelieve our canonical Jewish Book of Esther.

Here is Montefiore's review, to which he refers. Paulus Cassel, born Selig, was the convert brother of David Cassel:

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Marc Shapiro on the question of obligation of belief in the authorship of the Zohar.

You can read or download Dr. Marc B. Shapiro's article in the new issue of Milin Havivin here. The article is called "?האם יש חיוב להאמין שהזוהר נכתב על ידי רבי שמעון בן יוחאי"("Is There An Obligation To Believe that the Zohar Was Written By Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai?" ). While I thought the question was settled years ago (see here) and subsequently had to reconsider (here) you can read what Shapiro has to say in his interesting article. He brought some interesting sources to my attention, such as a Darke Moshe which says "שמעתי כי בעל ספר הזוהר הוא סתם רבי שמעון המוזכר בתלמוד שהוא רבי שמעון בן יוחאי," sounding a lot less committal than you'd think.

Once can also read some classic works on the question of the Zohar's authenticity:

R. Elijah Del Medigo - Bechinas Ha-das here

Yaavetz - Mitpachas Sefarim here

R. Moshe Kunitz - Ben Yochai here

Shir Rapoport - Nachalas Yehuda here

R. Leone Modena - Ari Nohem here

Shadal - Vikuach al Chochmas ha-Zohar, etc. link

R. Elia Benamozegh - Ta'am Le-shad here

R. Eliyahu Nissim - Ana Kesil here

R. Shlomo b"r Eliyahu Nissim - Aderes Eliyahu here

R. Moshe Yisrael Hazzan - Shearis Ha-nachalah here

R. David Luria - Kadmus Sefer Ha-zohar here

The above list is not meant to be exhaustive.

The entire issue of Milin Havivin 5 can be downloaded here.

Once can also read some classic works on the question of the Zohar's authenticity:

R. Elijah Del Medigo - Bechinas Ha-das here

Yaavetz - Mitpachas Sefarim here

R. Moshe Kunitz - Ben Yochai here

Shir Rapoport - Nachalas Yehuda here

R. Leone Modena - Ari Nohem here

Shadal - Vikuach al Chochmas ha-Zohar, etc. link

R. Elia Benamozegh - Ta'am Le-shad here

R. Eliyahu Nissim - Ana Kesil here

R. Shlomo b"r Eliyahu Nissim - Aderes Eliyahu here

R. Moshe Yisrael Hazzan - Shearis Ha-nachalah here

R. David Luria - Kadmus Sefer Ha-zohar here

The above list is not meant to be exhaustive.

The entire issue of Milin Havivin 5 can be downloaded here.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Abolitionism and eugenics in R. Elia Benamozegh's exposition of Gen. 9:25

Here is a very interesting comment, to say the least, in the commentary Em Lemasores of R. Elia Benamozegh (1822-1900). He says, commenting on Gen.9:25 ("Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.") that the Anti-abolitionists of England (he calls them אוהבי השעבוד Non abolizionisti באנגלאטירא, so he renders it as "lovers of slavery" in Hebrew) contend that black slaves aren't entirely human, but are partially descended from apes, specifically orangutans. The proof they bring is the size of their skull, which they say is smaller than all other men, and consequently their brain is smaller and similar to an ape's. But one should see the scholar Tiedmann who wrote a special book refuting this.

Now, I have to say that I doubt that he meant England, which already abolished slavery long before. As I noted here well into the 19th century some European Jews didn't seem to fully grasp, or care, that the United States wasn't English. I know that he says Angleterre, but it really only makes sense if he means the United States of America. If so, here would be another example of an inability to distinguish between the mother and the child, fully 85 years after the Declaration of Independence.

Now, I have to say that I doubt that he meant England, which already abolished slavery long before. As I noted here well into the 19th century some European Jews didn't seem to fully grasp, or care, that the United States wasn't English. I know that he says Angleterre, but it really only makes sense if he means the United States of America. If so, here would be another example of an inability to distinguish between the mother and the child, fully 85 years after the Declaration of Independence.

Monday, December 26, 2011

On Reverend's Handbooks and Bar Mitzvah speeches for American boys of a century ago.

One of the interesting phenomena of American Jewish life a century ago was the Jewish educational literature which reflected the relatively simple education available at the time - sometimes on the part of the author, sometimes on the part of the projected audience. There as a genre of "Reverend's hand-books," the best-known example by Simon Druckerman, published by Hebrew Publishing Company. These usually consisted of simple sermons in English and Hebrew for many occasions, and some basic texts, like the Kaddish; I think I've even seen one which included documents like a Get! (Jewish bill of divorce.)

One book in this genre was The Jewish American Orator (Der Idish-Ameriḳaner redner: a bukh fun 521 redes in Idish, English un Hebraish) compiled by George (Getzel) Selikovitch, a Yiddish writer who sometimes wrote under the pseudonym "Litvisher Philosoph" ("Lithuanian Philosopher"). In this book, some of the sermons are ascribed to himself, Selikovitch, and some to the aforementioned Litvisher Philosoph, which is also quaintly rendered as "Lithvassian Philosopher." The title pages of this book, printed in 1907 (Chanukah, no less, according to the Yiddish section), looked like this:

Selikovitch (1863*-1927) was not an ignoramus; he was writing and compiling these sermons and speeches for a simple audience. Before emigrating to the United States, he was an interpreter for the British army in Sudan and Ethiopia; the results of that experience were printed in a Hebrew book called Tsiurei Masa. Among other interesting things he writes is a conversation with a 16 year old slave girl named Aziza in the Sudanese King's harem (pg. 33).

The introduction includes two short biographical pages, where he informs us that he was born near Kovno and received a traditional education (Torah, Talmud, and the poskim). Orphaned at 16, an "Honorary Lieutenant" in Egypt at 22, where he learned Arabic and English, he eventually returned to Europe, where he penned many articles for Hameliz and Hamaggid, and befriended future celebrities like Eliezer Ben Yehuda. After another trip to the East, he emigrated to the United States, studied at the University of Pennsylvania, and moved to New York. There he wrote many articles and books in Yiddish, including a Yiddish guide to Arabic . For more complete biographical info, including a detailed description of the Arabic book, see Simon, Rachel - "Teach Yourself Arabic - in Yiddish" (MELA Notes: The Journal of the Middle Eastern Librarians Association; link).

Here he is:

An example of a table from his Arabic book:

Getting back to The Jewish-American Orator, here is the English Table of Contents, which gives an idea of what sort of occasions are meant to be addressed:

As you can see, it is heavy on the Bar Mitzvah material and also includes some sad signs of the times - For an Orphan to [sic] his Bar Mitzva, Funeral Oration at a Young Men's Bier, etc. (Not that I am under any illusion that such sadness has really diminished.)

Here are some samples. A "pshetel" for a Bar Mitzvah boy:

Another one penned by Selikovitz himself:

And here is an Address at the Engagement of an Orphan Girl, where her fiance is told that he is to be her father and mother, as well as husband:

* Mayer Waxman says he was born in 1856, but Selikowitch himself writes 5623 (1863) in Tsiurei Masa.

One book in this genre was The Jewish American Orator (Der Idish-Ameriḳaner redner: a bukh fun 521 redes in Idish, English un Hebraish) compiled by George (Getzel) Selikovitch, a Yiddish writer who sometimes wrote under the pseudonym "Litvisher Philosoph" ("Lithuanian Philosopher"). In this book, some of the sermons are ascribed to himself, Selikovitch, and some to the aforementioned Litvisher Philosoph, which is also quaintly rendered as "Lithvassian Philosopher." The title pages of this book, printed in 1907 (Chanukah, no less, according to the Yiddish section), looked like this:

Selikovitch (1863*-1927) was not an ignoramus; he was writing and compiling these sermons and speeches for a simple audience. Before emigrating to the United States, he was an interpreter for the British army in Sudan and Ethiopia; the results of that experience were printed in a Hebrew book called Tsiurei Masa. Among other interesting things he writes is a conversation with a 16 year old slave girl named Aziza in the Sudanese King's harem (pg. 33).

The introduction includes two short biographical pages, where he informs us that he was born near Kovno and received a traditional education (Torah, Talmud, and the poskim). Orphaned at 16, an "Honorary Lieutenant" in Egypt at 22, where he learned Arabic and English, he eventually returned to Europe, where he penned many articles for Hameliz and Hamaggid, and befriended future celebrities like Eliezer Ben Yehuda. After another trip to the East, he emigrated to the United States, studied at the University of Pennsylvania, and moved to New York. There he wrote many articles and books in Yiddish, including a Yiddish guide to Arabic . For more complete biographical info, including a detailed description of the Arabic book, see Simon, Rachel - "Teach Yourself Arabic - in Yiddish" (MELA Notes: The Journal of the Middle Eastern Librarians Association; link).

Here he is:

An example of a table from his Arabic book:

Getting back to The Jewish-American Orator, here is the English Table of Contents, which gives an idea of what sort of occasions are meant to be addressed:

As you can see, it is heavy on the Bar Mitzvah material and also includes some sad signs of the times - For an Orphan to [sic] his Bar Mitzva, Funeral Oration at a Young Men's Bier, etc. (Not that I am under any illusion that such sadness has really diminished.)

Here are some samples. A "pshetel" for a Bar Mitzvah boy:

Another one penned by Selikovitz himself:

And here is an Address at the Engagement of an Orphan Girl, where her fiance is told that he is to be her father and mother, as well as husband:

* Mayer Waxman says he was born in 1856, but Selikowitch himself writes 5623 (1863) in Tsiurei Masa.

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Shadal series #8 - To what does "Nothing Jewish is Alien to Me" refer?

People say that Franz Rosenzweig said "Nothing Jewish is alien to me" (Google rosenzweig "nothing jewish"), and perhaps he did. This was a play on a famed quotation from Terence (Terentius) "Homo sum, humani nil a me alienum puto" - "I am a human, I hold that nothing human is alien to me."

Some people, but not everyone, know that this Jewish twist on Terence was apparently first stated by Shadal (although it needn't take a genius to have punned it, and perhaps others before or after did so independently). Before I get to the location and context of Shadal's version, Judaeus sum, judaici nihil a me alienium puto - I want to show something wacky. Here is the first page of a missionary magazine called The Peculiar People:

As you can see, the motto of this magazine from Plainfield, New Jersey is "I am Jewish," etc. This is dated 1898. Shadal's letter, from 1842, was printed in the second volume of Igrot Shadal, published in 1894. However, we should not be misled in assuming that the magazine got it from Igrot Shadal, because it existed for a few years before 1894. Writing in 1892, a book about evangelism to the Jews explains that "Die Zeitschrift "Peculiar People" aber, an welcher auch Lucky, ohne seinen Namen zu nennen, mitgearbeitet hatte, wird von dem Sabbatharier Rev. William L. Daland (Westerly, Rhode Island) unter dem Motto: "Judaeus sum, Judaici nihil a me alienum puto" fortgesetzt." This may be before the second volume of the Igrot was published. I say may, because even though the second part was completed in a single volume 1894, it had been appearing in sections first.

In any case, writing in 1842 to Michael Sachs (the piyyut scholar and preacher about whom I wrote here; the same Sachs who was contemplated in Frankfurt as rabbi of the separatists, before hiring Hirsch) Shadal says the following:

All in all, this is a most interesting aside and it appears to be the origin of the saying ascribed to Franz Rosenzweig (and others): "I am Jewish, and nothing Jewish is alien to me." It was written by Shadal in 1842 to explain to someone that they shouldn't be surprised that he knows the Maharsha.

Some people, but not everyone, know that this Jewish twist on Terence was apparently first stated by Shadal (although it needn't take a genius to have punned it, and perhaps others before or after did so independently). Before I get to the location and context of Shadal's version, Judaeus sum, judaici nihil a me alienium puto - I want to show something wacky. Here is the first page of a missionary magazine called The Peculiar People:

As you can see, the motto of this magazine from Plainfield, New Jersey is "I am Jewish," etc. This is dated 1898. Shadal's letter, from 1842, was printed in the second volume of Igrot Shadal, published in 1894. However, we should not be misled in assuming that the magazine got it from Igrot Shadal, because it existed for a few years before 1894. Writing in 1892, a book about evangelism to the Jews explains that "Die Zeitschrift "Peculiar People" aber, an welcher auch Lucky, ohne seinen Namen zu nennen, mitgearbeitet hatte, wird von dem Sabbatharier Rev. William L. Daland (Westerly, Rhode Island) unter dem Motto: "Judaeus sum, Judaici nihil a me alienum puto" fortgesetzt." This may be before the second volume of the Igrot was published. I say may, because even though the second part was completed in a single volume 1894, it had been appearing in sections first.

In any case, writing in 1842 to Michael Sachs (the piyyut scholar and preacher about whom I wrote here; the same Sachs who was contemplated in Frankfurt as rabbi of the separatists, before hiring Hirsch) Shadal says the following:

"Since you mentioned in your letter the Hiddushei Maharsha, I will tell you a new thought I had about the Maharsha this week. 'About the Maharsha? What do you have to do with the Maharsha,' you ask?And before anyone says anything, yes, I am aware that he is acting like he discovered America, while this is, at least in theory, the way a Talmudist is supposed to read Rishonim and do this all day every day. However, Shadal's point here was that he of course knew that no one would have thought that he spent his spare time learning Gemara with Maharsha. In reality he was someone who went through Shas in 18 months beginning at age 16, and it is pretty clear that he knew his way in the sea of Talmud, even if he had instrumental motives for studying it - for example, he could not have written his grammar of Aramaic without becoming totally familiar with the language of the Gemara, and he could not have become familiar with it without studying it. Also, throughout his writings he exhibits a very great broadness in all types of Jewish learning; he quotes the Bavli, Yerushalmi, Tosafot, Rif, Tur, Zohar, She'elot u-teshuvot, and much more. While one imagines that this meant that he knew when, how and where to look things up when he needed to (like most scholars) it is apparent that he was no stranger to the traditional canon.

"I reply, "Judeus sum, judaici nihil a me alienum puto" - "I am a Jew, nothing Jewish is foreign to me."

"In Tractate Makkot 3b Rashi writes "if a borrower asks, 'Loan me money on condition that the Shemitta will not cancel my debt. . . " The Maharsha emends this Rashi to read "if a lender says . . ."

"At first though I agreed that this seemed correct, since it would be the lender who would need to say to the borrower "I loan it to you for ten years, on condition that you cannot default claiming that the Shemitta [which occurs every seven years] cancels it." But this explanation is difficult for me, since it seems to me that we should not ascribe this to a copyist's error. While it's possible that a scribe wrote "borrower" instead of "lender" (in Hebrew the difference is the addition or omission of a single letter), but to add the word[s] "loan me" would have to be his own invention, and this is uncommon [for a scribe to add something, rather than merely omit a letter by mistake]. So without another option, I said that Rashi did not write carefully due to haste. After that I thought, that perhaps he was old at the time, and his strength had waned, since when he reached page 19 of Tactate Makkot [it is written that] he died. After that I changed my mind and returned to Rashi's side, because his words seem to me to mean the following: in truth it is the borrower who needs to make this condition, not the lender, for the pauper required the sum for ten years and it is he who requests the loan. Because of the Shemitta, he would need to stipulate to the wealthy man that he will wave his right to the Shemitta cancellation of all debts. Then I considered that the requirement of release falls onto the lender (Deut. 15:2), not the borrower. Then my eyes were opened and I noticed that the language of this passage of the Gemara says "on condition that the Shemitta does not cancel it to me" meaning "that you should not cancel it to me." Rashi found himself compelled to to explain that it was the borrower who said this to the lender, for the lender is unable to say "on condition that the Shemitta should not cancel it to you," he could only say "on condition that the shemitta should not cancel it to me." Thus was Rashi blessed, that to the end of his days his words were pure, and they require study and exactitude. I said to myself, see how far a critic must go in moderately assessing something before passing judgment on the words of God-fearing men, who do not write their books in haste, for financial reward, or for honor. They write constantly to pursue the truth or that which is good."

All in all, this is a most interesting aside and it appears to be the origin of the saying ascribed to Franz Rosenzweig (and others): "I am Jewish, and nothing Jewish is alien to me." It was written by Shadal in 1842 to explain to someone that they shouldn't be surprised that he knows the Maharsha.

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

The Schutzjuden thank Karl Theodor

And here's part of a prayer service for the 50 year rule of the late, great Karl Theodor; the date of this service, held in Sulzbach, was July 20, 1783:

Candlemas or Chanukah?

Here's a post from a few months ago, that I think is relevant.

The English side from the Birkhas Hamazon A. Alexander's 1770 siddur סדר התפלה לפאר ותהלה:

The English side from the Birkhas Hamazon A. Alexander's 1770 siddur סדר התפלה לפאר ותהלה:

Candlemas? That's quaint. In a way I wish that's the way the Jewish-English language went. If Passover, why not Candlemas?

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Hebrew prayers for three condemned Jews, 1739.

Here's a pamphlet of a Hebrew prayer that a Dutch Clergyman named Willem Muilman prayed for three Jews who were sentenced to death and executed in the Hague in 1739. The Dutch translation is included. You can download the entire thing here: Gebed Van Willem Muilman Voor Drie Misdaadige - תפלה לגוליעלם מולמן בעד שלשת מרעים.

Here are some sample pages.

dsds

Here are some sample pages.

dsds

Monday, December 19, 2011

On the patriarch Abraham's Hassidic clothing and appearance

Here's a really interesting post on the question of whether Avraham Avinu wore a shtreimel and bekeshe, from Yeedle. He quotes a perceptive comment from a 20th century Chassidic rebbe about how the perceived garb of Abraham would be in the eye of the beholder.

Add Yeedle's על דא ועל הא blog ('On This and That') to your reader (link).

Add Yeedle's על דא ועל הא blog ('On This and That') to your reader (link).

Thursday, December 15, 2011

Doctor, doctor

Here are some typical images of Jewish doctors.

This is Yissachar Baer Teller of Prague:

His teacher, Yashar (Yosef Shalom Rofeh/ Delmedigo) :

Toviyah ben Moshe ha-Kohen (I guess that answers that question):

Abraham ha-Kohen (ditto) of Zante:

This is Yissachar Baer Teller of Prague:

His teacher, Yashar (Yosef Shalom Rofeh/ Delmedigo) :

Toviyah ben Moshe ha-Kohen (I guess that answers that question):

Abraham ha-Kohen (ditto) of Zante:

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

An anecdote evolves into an 18th century Jew joke.

Frederick II, Emperor of Prussia, was a historian. So he wrote a book called Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire de Brandebourg, published in 1750. (Write in German? Ew. Actually, Moses Mendelssohn would chastise him in a book review of his Poesies Diverses 10 years later, for writing his poetry in French, rather than German.) In 1751 an English version appeared, called Memoirs of the house of Brandenburg.

The following appears in it:

The Jewish Encyclopedia informs us that this Dutch Jew named Schwartzau was actually a Suasso, namely Antonio Lopez Suasso (link):

So that's the story: William of Orange borrowed 2 million something-or-other from a Jew named Schwartzau, who told him that he could pay it back if he succeeds in his military campaign against England. If not, he is prepared to lose it.

In 1800 an Encylopaedia of Anecdotes was published in Dublin, and here is how it tells it (under the heading Jewish Liberality):

Now it's almost Jew joke: "If you are fortunate I know you will pay me, if you are not, the loss of my money will be the least of my afflictions."

The following appears in it:

The Jewish Encyclopedia informs us that this Dutch Jew named Schwartzau was actually a Suasso, namely Antonio Lopez Suasso (link):

When William III. undertook his expedition to England in 1688, Suasso advanced him 2,000,000 gulden without interest and did not even ask for a receipt, merely saying: "If you are successful you may repay me; if you are not successful, I will be the loser." Frederick II. of Prussia commemorates this instance of self-sacrifice as the act "of a Jew named Schwartzau.""Schwartzau" was evidently either a sort of Dutch version of his name, or Frederick himself Germanized it, the same way I Anglicized "Friedrich."

So that's the story: William of Orange borrowed 2 million something-or-other from a Jew named Schwartzau, who told him that he could pay it back if he succeeds in his military campaign against England. If not, he is prepared to lose it.

In 1800 an Encylopaedia of Anecdotes was published in Dublin, and here is how it tells it (under the heading Jewish Liberality):

Now it's almost Jew joke: "If you are fortunate I know you will pay me, if you are not, the loss of my money will be the least of my afflictions."

"Shlomo" Shlomo Shlomo Shlomo Shlomo - an oral tradition about Rashi revisited

A few months ago I posted a little about a popular legendary story about Rashi. The story - with many variations, including variations about the hero of the story - is that Rashi was traveling in a foreign land, and he was unknown. Accused of thieving, he wrote שלמה שלמה שלמה שלמה שלמה on the door of the home where the robbery occurred. Puzzled by this cryptic message, the stranger - Rashi - was asked to explain himself. He vocalized the five words and showed that it meant "Shelamah shalma Shlomo salma shelemah?" or "Why should Shlomo pay for the entire [missing] garment?" From this they knew that Rashi was no thief, but a talented, profound scholar.

Here is one version presented as a riddle on an Ask the Rabbi forum (link:

Be that as it may, what is the origin of this legend concerning Rashi? The proper place to look for the legend and a bibliography relating to it is in Y. Berger's article Rashi be-aggadat ha'am (Rashi in Folklore) in a volume called Rashi: Torato Ve-ishyuto (New York 1958) and he does not disappoint. On pp. 162-63 he brings the story and the sources known to him. He quotes Rabbi Y. L. Maimon's version (which I posted in the first post) , and a close parallel where the hero is Ibn Ezra, printed by Naftali ben Menachem in his collection of Ibn Ezra legends (that version concerns Rashi too - on the other side!). The earliest source he found is the following, in a book printed in Chicago in 1902. The author, Abraham Hyman Charlap (b. 1862), says it is something he heard orally from his father, Rabbi Joseph Charlap. He also says that it has never before been printed in a book - but I will show that this is mistaken:

However, I found an earlier source. The Frankfurt University Library has a copy of a Yiddish book called Sefer Ma'aseh Rashi Z"L, which it placed online (link). Unfortunately no useful bibliographical data appears on the book itself, and the catalog entry is not much more useful. However, it does state (claim) that it is from circa 1800, and from some internal evidence I suggest that this is about right. (One piece is that the book is entirely vocalized, and it seems to me that the spelling and fonts suggest that period, rather than later. In particular, I note that it vocalizes the word רבי with two chiriks, something which disappears in the 19th century.)

It quotes the usual sources one would expect, such as Shalsheles Hakabbalah and Sefer Yuchasin. It also quotes She'erit Yisrael, a popular Yiddish book by Menachem Mann Amelander, printed in Amsterdam in 1743/4. This book presents itself as Sefer Josippon Part II. It was sufficiently popular that more than a century letter Gabriel Isak Polak published an annotated Dutch translation.

Now, legend had long made Rashi into a world traveler. The Shalsheles Hakabbalah even has a whole piece about how Rashi met the Rambam in Egypt, even though he admits that some people told him that they had a tradition that Rashi lived before the Rambam. Still, he writes, his heart tells him otherwise. This sort of thing was decried by Zunz at the end of his Toldot Rashi (link; "סוף דבר הכל הבלים").

But the makers and tellers of legends never asked Zunz for permission, so legends they made and legends they passed on. The Sefer Ma'aseh Rashi brings the legend of the five words spelled the same, and it brings it gleefully:

In this version, the story occurs in Egypt, where Rashi is trying to meet the Rambam, but only the servant is at home (maybe Peter?).

As you can see, the passage begins by quoting Amelander's She'erit Yisrael and it is not clear where or if it ends. If you look up the part that deals with Rashi in Egypt to meet Maimonides, you see that this story is not mentioned.

In case there's any misunderstanding, Amelander was also published in a Hebrew translation in Vilna in 1811. You can read the identical passage here or even here, in Dutch, if you are so inclined.

Thus, we have seen the Shlomo Shlomo Shlomo &c. story not only in 1902, but even in 1800. It gives no source, and in fact the source it has just cited (about Rashi meeting the Rambam) doesn't mention it. It seems that this is indeed a Rashi legend. A genuine oral tradition. We also saw the probable source of the riddle used in the story, which is either the Sefer Smadar itself or (more likely) the Massores Hamassores of R. Elijah Levita.

Finally, it is most interesting to note that the story is such a good one, and the riddle so clever, that a variation of the legend was printed in 1911, by a great-grandson of R. Shlomo Kluger (b. 1783) - and he says it happened to his ancestor! (link)

Finally, finally, here is Ben Menachem's version where it is Ibn Ezra who tried to meet Rashi, rather than Rashi who tries to meet Maimonides:

Here is one version presented as a riddle on an Ask the Rabbi forum (link:

Dear Yiddle Riddle people: The following is a story I read about Rashi in a child's Hebrew biography in perhaps fourth grade. Nobody I know has been able to solve the question without help. Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo ben Yitzchak) once went on a journey to a foreign city. On his trip, he wanted to visit a wealthy man to collect money for poor people. When he visited, the man was not at home, but his servant was. The servant said that he recognized the great Rashi as a thief who had previously run off with a set of his master's clothing and forced Rashi to pay for the clothing! Rashi wrote the following Hebrew word on the door five times in a row: The word was spelled "Shin Lamed Mem Hey." What did the message mean?As I said in the other post, this appears in R. Elijah Levita's Massoret Ha-massoret, as a quotation from a certain book called Smadar, which is quoted in various sources, but unknown to us. The context is completely different. The author of Smadar attempted to show that the Hebrew punctuation is necessary to understand it, therefore it cannot be said to have been invented much later than the writing itself. Here is what I wrote:

Masores Hamasores (third introduction) quoted the unpreserved Sefer Hasmadar by one Rabbi Levi ben Joseph which is the actual source for the observation that "שלמה" can produce the following five variations: "שֶׁלָמָה שַׁלְמָה שְׁלֹמֹה שַׂלְמָה שְׁלֵמָה."

C.D. Ginsburg's translation is:

As you can see, this quote by R. Levi ben Joseph is not a sentence at all! He merely gives 5 wods in a row, not meant to be strung into a sentence. This explains rather well why it is such an awkward sentence. ("salma shelema" - "the entire garment"? is this not strange?) As clever a mind must be to have thought of it, it is decidedly less clever to have taken R. Levi ben Joseph's five words and shaped it into a sentence.R. Levi b. Joseph, author of the book Semadar, says, at the beginning of his work, as follows: "If any one should ask, Whence do we know that the points and accents were dictated by the mouth of the Omnipotent? the reply is, It is to be found in Scriptures, for it is written, ' And thou shalt write upon the stones all the words of this law very plainly' (Deut. xxvii. 8). Now, if the points and accents, which make the words plain did not exist, how could one possibly understand plainly whether שלמה means wherefore, retribution, Solomon, garment, or perfect? " Thus far his remark. I leave it to the reader to judge whether this is reliable proof.

Be that as it may, what is the origin of this legend concerning Rashi? The proper place to look for the legend and a bibliography relating to it is in Y. Berger's article Rashi be-aggadat ha'am (Rashi in Folklore) in a volume called Rashi: Torato Ve-ishyuto (New York 1958) and he does not disappoint. On pp. 162-63 he brings the story and the sources known to him. He quotes Rabbi Y. L. Maimon's version (which I posted in the first post) , and a close parallel where the hero is Ibn Ezra, printed by Naftali ben Menachem in his collection of Ibn Ezra legends (that version concerns Rashi too - on the other side!). The earliest source he found is the following, in a book printed in Chicago in 1902. The author, Abraham Hyman Charlap (b. 1862), says it is something he heard orally from his father, Rabbi Joseph Charlap. He also says that it has never before been printed in a book - but I will show that this is mistaken:

However, I found an earlier source. The Frankfurt University Library has a copy of a Yiddish book called Sefer Ma'aseh Rashi Z"L, which it placed online (link). Unfortunately no useful bibliographical data appears on the book itself, and the catalog entry is not much more useful. However, it does state (claim) that it is from circa 1800, and from some internal evidence I suggest that this is about right. (One piece is that the book is entirely vocalized, and it seems to me that the spelling and fonts suggest that period, rather than later. In particular, I note that it vocalizes the word רבי with two chiriks, something which disappears in the 19th century.)

It quotes the usual sources one would expect, such as Shalsheles Hakabbalah and Sefer Yuchasin. It also quotes She'erit Yisrael, a popular Yiddish book by Menachem Mann Amelander, printed in Amsterdam in 1743/4. This book presents itself as Sefer Josippon Part II. It was sufficiently popular that more than a century letter Gabriel Isak Polak published an annotated Dutch translation.

Now, legend had long made Rashi into a world traveler. The Shalsheles Hakabbalah even has a whole piece about how Rashi met the Rambam in Egypt, even though he admits that some people told him that they had a tradition that Rashi lived before the Rambam. Still, he writes, his heart tells him otherwise. This sort of thing was decried by Zunz at the end of his Toldot Rashi (link; "סוף דבר הכל הבלים").

But the makers and tellers of legends never asked Zunz for permission, so legends they made and legends they passed on. The Sefer Ma'aseh Rashi brings the legend of the five words spelled the same, and it brings it gleefully:

In this version, the story occurs in Egypt, where Rashi is trying to meet the Rambam, but only the servant is at home (maybe Peter?).

As you can see, the passage begins by quoting Amelander's She'erit Yisrael and it is not clear where or if it ends. If you look up the part that deals with Rashi in Egypt to meet Maimonides, you see that this story is not mentioned.

In case there's any misunderstanding, Amelander was also published in a Hebrew translation in Vilna in 1811. You can read the identical passage here or even here, in Dutch, if you are so inclined.

Thus, we have seen the Shlomo Shlomo Shlomo &c. story not only in 1902, but even in 1800. It gives no source, and in fact the source it has just cited (about Rashi meeting the Rambam) doesn't mention it. It seems that this is indeed a Rashi legend. A genuine oral tradition. We also saw the probable source of the riddle used in the story, which is either the Sefer Smadar itself or (more likely) the Massores Hamassores of R. Elijah Levita.

Finally, it is most interesting to note that the story is such a good one, and the riddle so clever, that a variation of the legend was printed in 1911, by a great-grandson of R. Shlomo Kluger (b. 1783) - and he says it happened to his ancestor! (link)

Finally, finally, here is Ben Menachem's version where it is Ibn Ezra who tried to meet Rashi, rather than Rashi who tries to meet Maimonides:

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

A work by Abraham Ger of Cordoba.

You can read or download a very important and interesting manuscript here. I am referring to Rabbi Mordechai Luzzatto's (1720-99) Hebrew translation of a polemic by Abraham Ger (more properly Guer, but also known as Gher) of Cordoba, a 17th century Spanish convert to Judaism, formerly named Lorenzo Escudero. His book, writtenin approximately 1650, was called Fortaleza del judaismo y confusión del estraño. Luzzatto called it צריח בית אל (Judges 9:46).

As you can see, the copyist of this manuscript apparently believed that he was of Converso descent (מאנוסי קורדובה). This is strange, in light of his name. I believe Yosef Kaplan showed that he was not a New Christian at all.

Here is the introduction:

Readers who are interested in a sample of the work in English should see pg. 290 in The Fifty-third chapter of Isaiah according to the Jewish Interpreters edited by A. Neubauer and S.R. Driver (1877) (link).

As you can see, the copyist of this manuscript apparently believed that he was of Converso descent (מאנוסי קורדובה). This is strange, in light of his name. I believe Yosef Kaplan showed that he was not a New Christian at all.

Here is the introduction:

Readers who are interested in a sample of the work in English should see pg. 290 in The Fifty-third chapter of Isaiah according to the Jewish Interpreters edited by A. Neubauer and S.R. Driver (1877) (link).