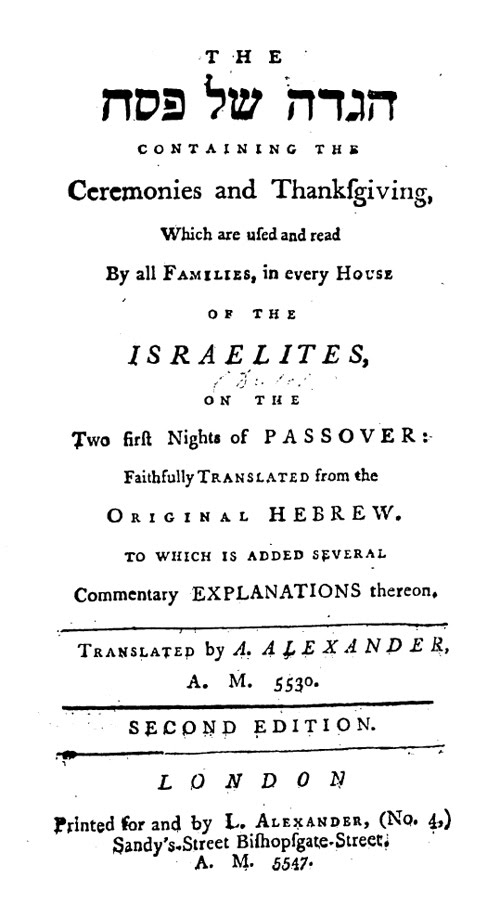

This is the second edition, printed in 5547 (1787), by his son Levy ("L. Alexander"). According to the title page the translation proper was made in 1770. Alexander Alexander (אלכסנדר בר יהודה ליב) was a Hebrew printer active in London in the 18th century.

The second page includes an engraving of Moses slaying the Egyptian, with the caption "Engraved for the Hebrew & English Hawgoda," - and you think we have transliteration problems today. According to the book Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress the engraving was not for this Haggadah, as the caption misleadingly suggests.

This Haggadah includes interesting customs and interpretations. Here are some of them:

1) In explaining how three matzos are to be set, representing Kohen, Levi and Yisrael, Alexander writes that all three matzos have one, two or three "notches" made into them so that the special designated matzos will not be mixed up. Thus, the Kohen matza laid on top has one notch. He also writes that a fourth matza is added, known as the ספק (i.e. doubtful) because if one of them breaks, it will be used instead. Since we don't know which one it may be used for, hence the doubt, etc. So if anyone spends a lot of time today trying to ensure only whole matzs are used, or has cause to fret while some family member does it, here is a Haggadah where you are instructed to make notches in the matza.

2) He writes that one places "a stick of horse reddish [sic] with the green top to it" on the seder plate. He notes that the reason is "in rememberance of the hard labor, which made the eyes water, and the green top is in remberance of the bitterness of the labour." This is an interesting syncretistic explanation, is it not? Takes care of the problem that horseradish is sharp, not bitter.

3) Writing of the Charoses, he states that it is "made of bitter almonds, pounded with apples, &c."

4) He writes that the Master is given "three chairs set close together, in imitation of a couch." I guess they had armless chairs but not couches in London.

5) "The meannest of Hebrew Servants are seated at the Table . . . with the rest of their superiors."

6) He writes that the Kos shel Eliyahu is drank by the youngest.

7) He explains that the reason why Keha Lachma Anya "is in Caldaic תרגום language, is on account it was customary with our ancestors to elevate their table on some high place in the room and open the door, and invite the poor to come and partake of the Psachal; and this being the language of Babel, the country where they were captives at the time this hgdh was first composed, and the common sort of people at that time, did not understand the Hebrew, therefore they were addressed in that language."

8) He translated Bene Berak as ". . . were entertained amongst the children of Berak." The foonote explains that this is "A name of a place inhabited by Proselytes, Jews descended from Haman."

9) In Vayehi Sheamda he very circumspectly translates שבכל דור ודור עומדים עלינו לכלותינו as "even in several generations they arose up against us to destroy us."

10) Tze U-lemad, "Go forth and learn how Laban the Amarite thought to *serve* our father Jacob." (!)

11) A lot of the language is quaint simply because of the linguistic distance from our own time. So for רבי יהודה היה נותן בהם סמנים he translates "Rabbi Judah makes remarks thereon." In the very next paragraph were are told of "Rabbi Jose of Gallicia." So if anyone ever asks you if any of the Tannaim were Galicianers, you can say truthfully that, yes, according to Alexander Alexander of London, רבי יוסי הגלילי was a Gallician.

12) He has instructions to use the green top (leaves) of the "Horse-Reddish" for Marror, but a "[cut] piece" of the horseradish for Korech. It also doesn't seem like you are supposed to make a sandwich (i.e., marror between two layers of matzah). Rather, he writes that you take the matzah and marror and "put one on the other."

13) Everything is translated into English; however Echad Mi Yodeya is translated to Yiddish and English, and Chad Gadya is only translated to Yiddish (Ein Zicklein). In addition, the Shelah's increasingly rare version of Adir Hu, the נון בויא דיין טעמפיל שירה is included.

As usual, the English here is . . . interesting. For example, in Echad Mi Yodeya you get lines like "Nine is the nine months of pregnance."

Here are four pages from the introduction, which I partially covered.

my favorite old englishism is "meanest hebrew servant", which made its way into the levi haggadah and then american haggadot.

ReplyDeleteYou know, it's funny. Sometime I read too much from other centuries that I don't even notice things like that any more. For those who didn't get that, "mean" meant "low rank" or "course" in the 18th century.

ReplyDeleteאור לארבעה עשר, I should be doing more productive things than commenting on blogs. (Yes, I have already done my Bediko.)

ReplyDeleteNonetheless, I note with delight that this Haggodo, from 1770, has both Yishtabbach and Nishmas Kol Chai end with חתימות, as per the Rashbam. This is exciting to me, because until now, the latest Ashkenazic Haggodo that I had seen with this feature was that published by Shlôme Zalmen Aptrud, in Frankfurt-am-Main, in 1727.

"Go forth and learn how Laban the Amarite thought to *serve* our father Jacob." Another old-fashioned usage: to "serve" can mean to "behave toward" or to "treat," as in, "He was cruelly served."

ReplyDeleteAlso, "Amarite" is apparently a spoonerism for "Aramite."

Aren't bitter almonds poisonous?

ReplyDeleteInteresting that he doesn't seem to realize that Aramaic was the common language in Israel as well (which is where the Haggadah was really written).

Also interesting that he knows that Bnei Brak is a place and yet translates it literally.

>Aren't bitter almonds poisonous?

ReplyDeleteThen it certainly would remind you of the bad times, wouldn't it?

In general we must always remember that a word doesn't necessarily signify in earlier times what it does now.

Surely in small doses it won't kill you. Here's a quote from a book from 1775:

"BITTER Almonds are poisonous to animals, particularly to birds. In the human body, they act as resolvents and aperients. In emulsion or with sugar they are diuretic, and an anthelmintic; but spirits, flavoured with bitter almonds, have proved poisonous to the human species. It has been experienced, that ten drops of a red oil (like to that of the laurel, of a kernelly flavour and taste) distilled in the same manner from bitter almonds, (after the sweet oil has been expressed) mixed with an ounce of common water, in like manner, will kill a dog in about half an hour."

So it seems plausible to be used as an ingredient then.

As for Bene Berak, although of course it's a place it's also named for the children of Berak; whether that's the name or the weather phenomenon I cannot tell you. I also saw 18th century biblical researches which try to understand the place name. So while unusual (I mean, would anyone think to translate Heliopolis as "Helio City" or, worse, "Sun City?")

See here for a critique of a century later, where Kaufmann Kohler makes fun of Rodkinson for translating Bene Berak in the same manner.

And everyone gets a cup of wine, which wasn't always the case in the Ashkenazi world (I learned that here, of course).

ReplyDelete