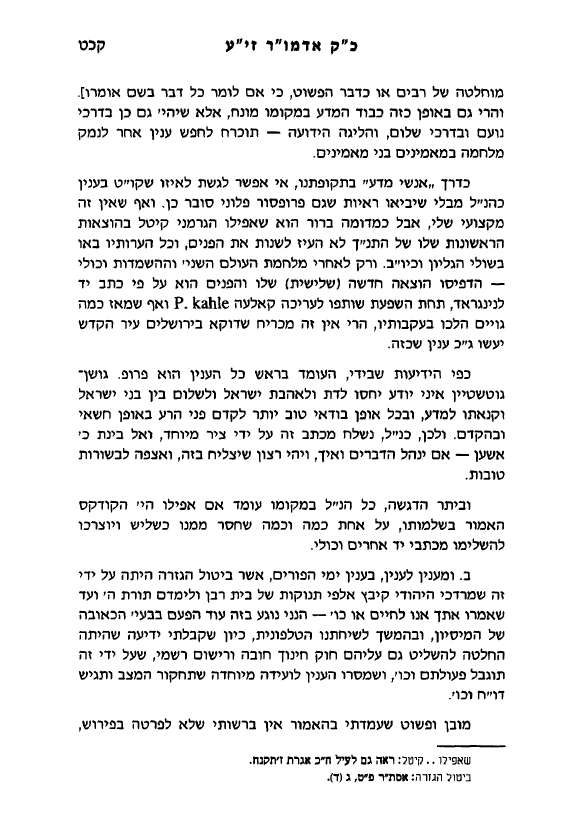

Here's an interesting excerpt from a 1964 letter of the Lubavitcher Rebbe (Iggeros Kodesh v. 23):

Speaking about manuscripts and so forth as it relates to printing Tanachs, he is saying in the second paragraph that even the German professor Kittel did not change the text of Tanach in his Biblia Hebraica.

I think this is a pretty good illustration of one of the reasons why the Lubavitcher Rebbe so appealed to educated non-Chassidim, and impressed his own Chassidim with his broad knowledge. How many other Rebbes - or Rabbis - have ever even heard of a Biblia Hebraica, let alone know what it is like, let alone know who Kittel was, let alone know who Paul Kahle was, etc? It is somewhat interesting that he is critical of using the Leningrad Codex as its basis - the Artscroll Stone Chumash uses it (see here).

You see he really knew what was going on, and therefore he could have intelligent conversations and communications with all sorts of people about all sorts of things. Unfortunately this is also an example of one of the pitfalls of broad knowledge, for it incorrectly states that the 3rd edition of Biblia Hebraica appeared after the war, whereas it actually appeared in 1937. Also, the truth is that "our mesorah" is really - at best - the second Rabbinic Bible with adjustments by Minchas Shai and other shadings to conform to specific rules and traditions. Kittel's edition certainly wasn't really the 2nd Rabbinic Bible updated for rabbinic Jews.

Is it possible that the Rebbe was referring to the 7th edition (Stuttgart 1951), which is also sometimes called the third edition? See the book "Textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible", by Emanuel Tov, page 375, where Tov states this: http://books.google.com/books?id=U1UfMyO-RiEC&lpg=PA375&ots=cxLJMp0GqO&dq=3rd%20edition%20of%20Biblia%20Hebraica%20p%20kahle&pg=PA375#v=onepage&q&f=false

ReplyDeleteIt is - perhaps it is even likely - but it's still a mistake, since Leningrad 19a was used in 1937. It's not a huge deal, it's just my illustration of how broad knowledge sometimes leads to neglect of pedantic (but factual) details. And, of course, sometimes pedantic details are quite important.

ReplyDelete"It is somewhat interesting that he is critical of using the Leningrad Codex as its basis - the Artscroll Stone Chumash uses it"

ReplyDeleteBut not for spelling (letters).

I think it does. Naturally they make the necessary Minchas Shaian type adjustments, but they have to start with something. In this case it's whatever e-version of Biblia Hebraica 3/ Leningrad 19a they used.

ReplyDeleteNot sure what you mean. Letter-wise, Artscroll ALWAYS follows the 2nd R.B. agaist Leningrad.

ReplyDeleteI mean spelling differences such as WaYehi/WaYihyu (Gen 9:29) or Ptzua Dakah (alef v hei in Deut 23:3).

Once you make all the alternations, it doesn't really matter where you started.

What I mean is that in general Jewish Chumashim don't follow one specific printed or manuscript text slavishly. There are various minhagim and halachos which supersede whatever might be in any particular text. So a question like aleph/ heh in daka will not be resolved by what it says in one tikkun, but by what the prevalent practice or perceived psak is.

ReplyDeleteThat is true, but there is no reason to be surprised that Artscroll would follow the "ashkenazi chareidi" spelling (as opposed to a consensus of all ancient manuscripts supported by the Yemenite tradition).

ReplyDeleteI'm not saying it's right or wrong, I'm saying it's expected from Artscroll. Therefore I find the claim that their chumash is based on Leningrad a bit misleading.

"So a question like aleph/ heh in daka will not be resolved by what it says in one tikkun"

Not like it's 1525...

>That is true, but there is no reason to be surprised that Artscroll would follow the "ashkenazi chareidi" spelling (as opposed to a consensus of all ancient manuscripts supported by the Yemenite tradition).

ReplyDeleteAnd no one is surprised. FTR I think it should spell it with the heh.

Incidentally, in the "Pathways to the Prophets" book by Rabbi Yisroel Reisman, he discusses this and says (pg. 351): "It is interesting to note that although our Sifrei Torah spell dakah with a hei, when this word appears in the Gemara and Shulchan Aruch (and in most Rabbinic sources), it is spelled with an aleph. I have no idea why this is so."

All I could think is "Because . . . that's how the word is spelled? Do you not say Tefilla le-Moshe every shabbos morning?" Apparently not only is he unwilling to conclude that it's a mistake, that possibility can't even occur.

>I'm not saying it's right or wrong, I'm saying it's expected from Artscroll. Therefore I find the claim that their chumash is based on Leningrad a bit misleading.

They said it themselves.

S.,

ReplyDeleteCan you comment on the fact that spelling was never realy canonized until a century or two ago in the secular world. I think it is remarkable that the Jewish law required perfect spelling...

Sure. First of all, Hebrew (and all triliteral Semitic languages) are different from European languages, because they don't really use vowels. In addition, the correct consonants are generally obvious in Semitic languages - stable spellings are much easier. Since European languages all use adapted versions of an alphabet compiled for the use of another language (Latin) every one of the languages struggle to superimpose that foreign alphabet onto it. A quick example would be the sound conveyed by /sh/ in English, or shin in Hebrew. It is immediately obvious that no single letter exists in English for that sound. Secondly, /sh/ isn't the only way to express that sound, but sometimes /s/ alone, or /ss/ or /ch/ are used. It's a mess. Secondly, until say 3-400 years ago, all European vernaculars had very little prestige altogether (like Yiddish) and so 1) no efforts were made to stabilize the spelling, since they were only used in ephemeral communication, and also no efforts were made to impede changes in pronunciation. Furthermore, even if they had wanted to do that there were so many regional variations that you couldn't settle on one if you wanted to.

ReplyDeletecont.

Plus what to do when pronunciation changed? Two hundred fifty years ago some experimentation was made with changing the spelling. Thus, people no longer said, let's say, "I joined (join-ed) him at the party." They said "joind" like we do. So some people would spell it "join'd" dropping out the e which was no longer pronounced (pronounc'd). In the end languages like English and French basically settled on retaining archaic spellings, even though the pronunciation had changed. Weird, but that's what we do. In French they were "aout" for "August" but pronounce it "oo." Yet "aout" itself is an evolved, slurred form of the Latin "august." In addition, even the alphabets themselves were in a state of flux. Thus it wasn't clear if j or y were separate letters, or if u and v were, or if there was or should be a letter like w (or maybe it should be vv [two vees]).

ReplyDeleteBy contrast, Latin and Greek were prestigious language, and grammarians invested efforts into those languages and they were much more uniform. Still, they lacked the natural ease that Hebrew and Arabic had being triliteral and naturally lacking vowels.

cont.

cont.

ReplyDeleteIn addition, both Hebrew and Arabic were sanctified languages, with a specially sanctified text. This accounts for the care put into the spelling of those texts (halacha too, but that is just a reflection of the care). But take other Hebrew or Arabic texts. Not as much care there, right? Our non-Bible texts contain great variations. Even though it is easier to spell things one way in Hebrew, this didn't stop switches between mem and nun, samech and sin, etc. There never was a lexicon of the official Hebrew spellings for anyone to consult. The closest thing was the Bible itself, but 1) clearly that could not stop what we call Mishnaic Hebrew from using nun instead of mem, and 2) you had to be both learned enough to know how words were spelled in the Bible and for some reason possessing the desire to conform your own spellings to it for that to make a difference. Finally, even in the Bible itself the spellings are not perfectly consistent.

So I think in general the answer is that in reality consistent, stable spellings in alphabetic languages depend on the need and desire for it, the quality of the language itself, and the devising of a plan for implementing it.

Yet even with Hebrew, frankly no one reads Hebrew like the Tiberian masorah. Apparently the only Jews who read Hebrew like the Tiberian masorah were the Tiberians. So, like the Latin alphabet superimposed onto English, all Jews with their own tradition put dots and dashes all around the letters and - at best - try to somehow make it work, and all of us basically fail at it to varying degrees. It stares us in the face and most of us don't realize it. Still, at least the text itself is fixed.

"FTR I think it should spell it with the heh."

ReplyDeletePlease elaborate.

Although it is true that mesoros have been obliterated in the past, I don't believe in obliterating them deliberately in the future. Abraham Geiger once thanked God that printing was invented centuries before the Vilna Gaon, because if it hadn't then the Gra's many emendations would have been incorporated and erased the textual history of so many rabbinic texts.

ReplyDeleteFunny, because it was precisely the printing press that caused the obliteration most mesoros and creation of untouchable canonical versions.

ReplyDeleteBTW (It is claim that) GRA was a proponent of Dakah with Hei.

True about the press, but on the other hand it also created hard copies, as it were. People hand corrected manuscripts, but they didn't do that to printed texts.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I'm just saying that I don't want Torah scrolls to be changed en masse unless it came with a "track changes" feature, or the edit history like Wikipedia.

"Anyway, I'm just saying that I don't want Torah scrolls to be changed en masse unless it came with a "track changes" feature, or the edit history like Wikipedia."

ReplyDeleteHalachically, it is generally accepted that spelling differences do not render Torah scrolls invalid unless you can establish that they were copied inexactly from another scroll. The Talmud discusses our ignorance of haseirot and yeteirot, and there is no evidence that Chazal wanted to establish a normative version vis-a-vis most of those types of spelling errors that do not influence a word's meaning.

I agree, but not everyone does. Okay, maybe in reality there isn't much movement on Torah scrolls, but witness the brouhaha over writing Neviim based on the Aleppo Codex. Furthermore, if sifrei Torah are highly uniform, it's because of a process.

ReplyDelete