Paul Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz's monumental work The Jew in the modern world: a documentary History is an incredible 700+ page sourcebook of various documents relating to modernity. Some, like "the Jew Bill" of 1753 are already in English, but many others are translated from Hebrew, German, French, Italian, etc. It is an incredible mix of highly interesting material, a sermon by R. Ezekiel Landau, a responsum by R. Moses Sofer, pro and con Reform polemics, learned material and legal material and much much more. But everyone makes mistakes.

Below is the section titled An Ultra-Orthodox Position, which is basically a translation of a footnote and some other parts in R. Akiva Joseph Schlesinger's Lev Ha-ivri (1864). The Lev Ha-ivri is a 100 page commentary on the ethical will of the Chasam Sofer, which is kind of wild, if you think about it - I mean, the Chasam Sofer thought that three or four paragraphs was enough to convey his deepest religious emotions to his family. In this book 5 or 6 words can generate a densely packed page filled with many hundreds of words of commentary, and a lengthy footnote or two.

I'll summarize the piece, since not everyone will want to read it. A learned and pious rabbi who preached his sermons in German was hired. Maharam A"sch (Eisenstadter) said that to think this is to follow the Yetzer Horah. Today they appointed a learned, pious rabbi who preaches in German, but next they'll hire someone who speaks German, but isn't learned or pious. Eventually they'll hire a gentile. And the story gets far more heated.

Here it is in the original:

and in The Jew in the modern world: a documentary History:

Here's what happened. I was looking for something relating to Targum, and a search of the term "we translate" resulted in this very entry. So I started reading, and as you can see, the text says "the gaon, Rabbi Meir Ish Shalom." My very first reaction was "Huh?" - because Rabbi Meir Ish Shalom was a critical scholar, co-head of the Vienna Beis Midrash with Isaac Hirsch Weiss and the primary teacher of Solomon Schechter. Then in about two seconds I quickly thought "Oh, wait. There must have been another Rabbi Meir Ish Shalom." Then I thought, hold on, it probably says "A"sh" (ie, Aleph"Shin"). And then I thought, wait, so that's Maharam Ash, Rabbi Meir Eisenstadt. Then I looked in the footnote and it reads "Rabbi Meir Ish-Shalom (Friedman: 1831-1908) was a rabbinic scholar who published highly acclaimed critical editions of midrashic and aggadic works."

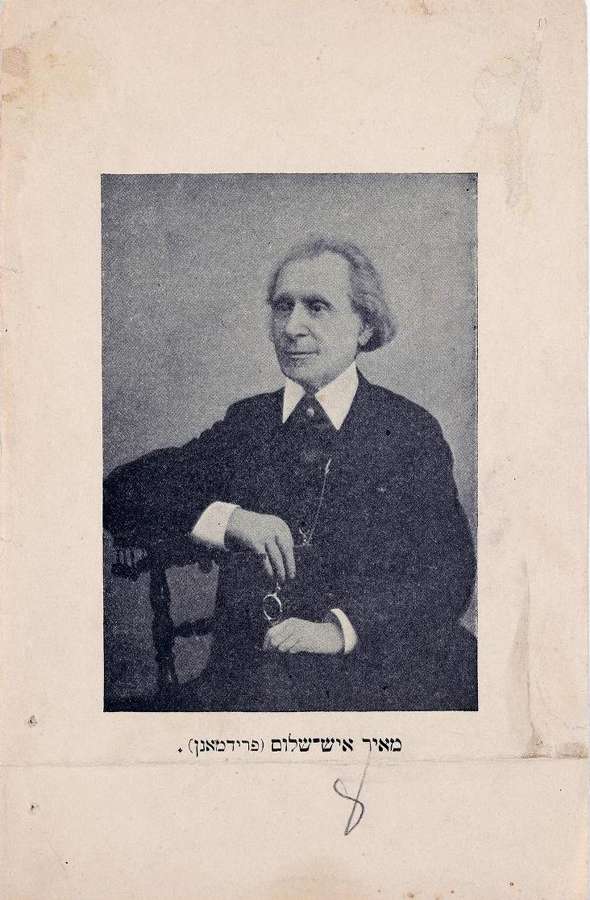

So what indeed happened was the the acronym was misunderstood, and not only was it misinterpreted but it wasn't enough to assume it was some Ultra-Orthodox Rabbi Meir Ish Shalom-the wrong man (indeed, one who never lived), but at least it would make sense - but the text assumed it was Schechter's teacher, depicted below:

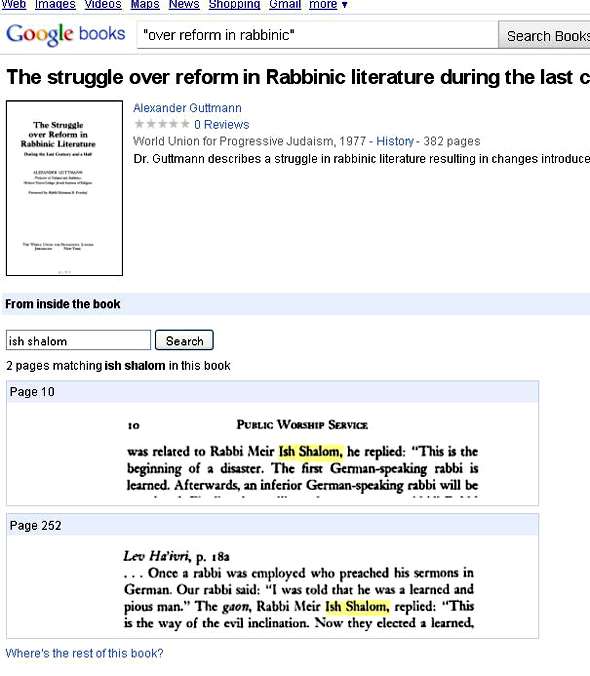

Quite amazing. In fact, what happened was this was someone else's mistake and this book just passed it on. The footnote says that the source is Alexander Guttmann's The Struggle Over Reform in Rabbinic Literature During the Last Century and a Half (New York, 1977) pp. 252-57. I haven't seen that book, but snippets are viewable on Google Books:

It cannot be stressed enough: everyone makes mistakes. It's a pity I have to even say that. Nevertheless mistakes can often be cleared up just by checking. One gets the sense that in compiling The Jew in the modern world no one bothered to even look at the original, to say nothing of how the rabbi in that footnote (who is even more vehement and stringent than the Chasam Sofer on the issue!) was confused with Meir Ish-Shalom.

Great post, good critical thinking on your part. The second time you mention Maharm Esh's name, you wrote "Eisenstadt" and not "Eisenstadter." Meir Eisenstadt was the name of the Panim Me'irot.

ReplyDeleteThe Ari spoke Yiddish on the Sabbath?! Not that he couldn't have known the language, but he was particular to speak LhQ on the Sabbath. (Though his own Ashkenazic father died when he was an infant, there were Ashkenazim in Saphed, and even Egypt, from whom he could have learned the language.)

ReplyDeleteOf course, this is second hand, but the Yiddish phrase is full of Germanisms, especially in spelling.

ReplyDeleteLipman,

ReplyDeleteMaybe that's because yiddish (deitsch) of Burgenland (today border of Austria and Hungary) and Oberland (north-west of the Hungarian kingdom, today mainly Slovakia) WAS "full of Germanisms", i.e. it was much closer to mainstream German that the yiddish in Galitzia or Lita.

Also, strictly speaking, word loans from standard German to one of the German dialects are not really Germanisms.

MG, he doesn't say Yiddish, although I agree it is implied. He may have known that he spoke Lh"K but considers it the same thing. Alternatively, he assumed it was Yiddish since the Ari was Ashkenazi. Possibly there is even a source that asserts this, but I don't know.

ReplyDeleteS.: Good point-- it was the translator who added the word "Yiddish", in brackets.

ReplyDeleteAt the risk of stating the obvious, this is an interesting vignette that still reverberates today -- the debate of whether making Judaism more accessible to the masses is a slippery slope, a dilution of tradition, tacit approval of secularism, and a recipe for laxity and laziness.

ReplyDeleteIdealists still maintain that s'farim and drashot should be the exclusive province of Lashon Hakodesh, Aramaic or Yiddish. They believe that scholarship is not only academic, but experiential, and that if you're going to study Jewish texts, you should adopt an approach of full immersion.

These milieus will still not countenance an Artscroll siddur or gemara. Perversely, they may not be thrilled that daf yomi has become so successful. Nor, I suspect were there predecessors thrilled when Greek was grudgingly deemed to be kosher enough.

er, "their" predecessors, not "there" predecessors

ReplyDeleteYou know, I forgot that I didn't include the full text, because my only point was about the footnote. In the text it is written this way:

ReplyDeleteדלשון יהודית דילן יש לו דין כלשון הקודש וכן הוא בספר מעין גנים וכן שמעתי וראיתי בשם האר"י הקדוש ז"ל אשר לא דיבר דיבור חול בשבת ובלשון שלנו דיבר ואמר דברי מוסר ותורה ואמר דהלשון שהסכימו היהודי והוא מיוחד ביניה' יש לו קדושה ודינו לשה"ק ועל כן מצוה רבינו ז"ל שלא ישנו לשונם בזמן הזה והוא לשון היהודית דילן...

I think it is *possible* he meant Yiddish, but maybe he meant Ladino or Judaeo-Arabic. And as you can see, the translator misunderstood this as well. It doesn't mean "he used no secular language" on Shabbos. It means he didn't speak of secular topics.

So much for translations. We should fast.

It doesn't mean "he used no secular language" on Shabbos. It means he didn't speak of secular topics.

ReplyDeleteIt means both.

I meant contextually. I'm right.

ReplyDeleteShimon S.,

ReplyDeleteno, the features that are, at least on the level of spelling, germanisms are common to all dialects of Yiddish, including Central Yiddish. And, frankly, I haven't a clue what you're saying about German dialects.