"Jewish Censure on the Pugilists, &c. employed at the Uproar in Covent Garden Theatre.-The Rev. Solomon Hirschell, High Priest of the Jewish synagogue, has caused 100 itinerant Jews to be struck off the Charity List, for six months, for making a noise at Covent Garden theatre ; he has also warned them of excommunication, in case they should be guilty of the like again."

Huh?

The story is as follows. In 1809 London's Covent Garden Theatre hired a bunch of Jewish bouncers. They were pugilists, that is, boxers.

First of all - not necessarily much different from today - many, if not most, people who fought for money were not of the highest social classes, the most educated, etc. There seem to have been a good number of Jewish pugilists, and these naturally came from the poor class, immigrants, etc. Although some made good money, most certainly did not. (I could insert something about Daniel Mendoza or Dutch Sam at this point - both of whom were involved in the situation in this post - but that's probably for another post, although see the end of this post for something interesting.)

Now in reality these people were probably a mixed bag. Some may have been pretty nasty pieces of work, some probably less so - but all of them were from disadvantaged backgrounds. As you can see by the notice, they all relied to some extent on Jewish charity. And 200 years ago boxing was in even less repute than it is today. Jews in England of this period (as in almost everywhere else in Europe) had a reputation for being uncouth at best, and criminals at worst. A lot of people don't realize it, but in certain places - 200 years ago - people did not feel safe around Jews, at least of the lower class. This may be surprising to some, but it shouldn't be. It doesn't take a whole lot of imagination to superimpose this image onto contemporary groups whom people associate with crime and are afraid of.

So the Jewish poor, especially of a certain kind, especially boxers, especially those who could be hired toughs, were naturally looked down upon - and a great embarassment to the gentle class of Jews.

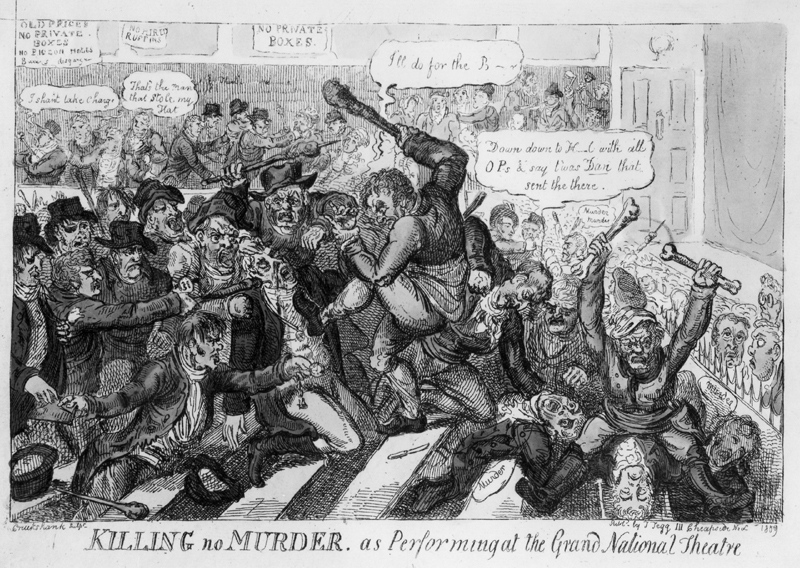

So what happened was, a theatre which had burned down was reopened a year later, with more expensive ticket prices and fewer cheap seats. During the first few weeks, the audiences reacted by being exceptionally rowdy, disturbing the perfomances. So the management hired these Jewish boxers to reign in the crowd - sort of like the Hell's Angels doing security for the Rolling Stones at Altamont.

What do you think happened? The bouncers bounced, and the audience got worse. They began to shout comments like "Old Clothes!" "Lemons and oranges to eat!" "Any bad shillings?" These refer to the stereotypical jobs poor Jews engaged in at the time, sellers of old clothes and oranges. By all accounts these sellers were - or were perceived - the way the squeegee men in New York City were 20 years ago. Annoying, vaguely menacing, and a threat to public order. The line about bad shillings obviously refers to another things Jews were commonly seen as being involved in.

This situation led to fights, which spilled out onto the streets. Apparently some of the onlookers at these fights had their pockets picked by Jews (another thing, of course).

Basically, the entire situation almost became a race riot, which was narrowly avoided by firing the boxers-bouncers. After a few weeks the whole situation died down when management agreed to lower the prices.

Here's a contemporary image of the incidents:

As you can see by this little piece at the top of the post, the "respectable Jews" were mortified, and who can blame them? The official response was to stop giving these 100 vagrant-pugilists whatever charity they received through the Great Synagogue for six months, and also to threaten them with excommunication.

Rabbi Solomon Hirschell's (only) biographer, Hyman Simons, pointed out that these people were unfortunates who 1) really needed the money and 2) probably had no clue what excommunication meant. Thus he is unimpressed by this reaction, clearly motivated by public opinion. Simons in general feels very warmly toward Hirschell, but he points out that one of the issues the rabbi really dealt with was the threat of Christian missionaries who were very active then. Presumably cutting off 100 marginal Jews just exposed them to these missionaries. But see this post for a story about Rabbi Solomon Hirschel and a boxer).

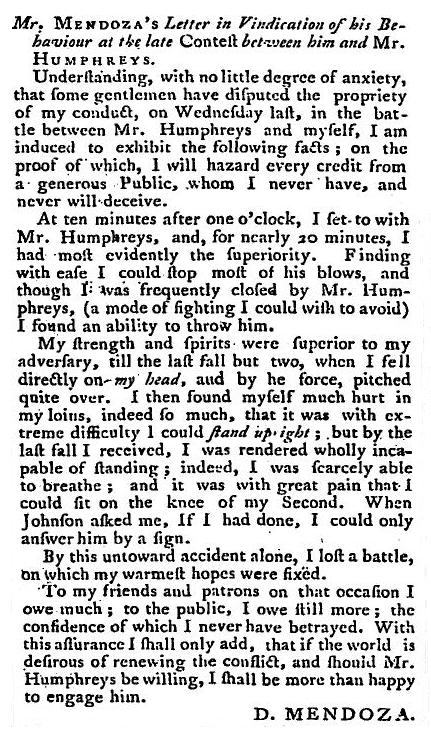

I said I'd post something interesting about Daniel Mendoza, an inventor of so-called scientific boxing. I won't give the details regarding his fights with Humphreys in 1788, but needless to say the trash talking made it to the press. How did a boxer talk in 1788? None of this "fly like a butterfly, sting like a bee" stuff. Here's Daniel Mendoza's letter (although of course it may have/ probably was ghostwritten for him):

That is one classy wordsmith of a pugilist.

Maybe they were actually Hittites.

ReplyDelete(Frequent readers of onthemainline will get that bad joke.)

- Phil

They were indeed Hittites.

ReplyDeleteHave you read David Liss's novels "A Conspiracy of Paper" and "A Spectacle of Corruption?" Their protagonist is loosely based on Daniel Mendoza, I believe.

ReplyDeleteOne thing I never understand about some of these newspaper clippings you post is why the letter 's' so often looks like a lowercase 'f' -

ReplyDeleteWas their English corrupted, or is mine?

Neither. The lower case letter s used to have two forms. At the end of a word it would always look like the lower case s we are familiar with. In the middle of words it would look much like a lower case f (although not identical). At the beginning of words the normal lower case s or the long s (as it is called) may or may not have been used; it seems that it was optional, either could be used, although older books seemed to favor the long s, while the closer we get in time to us, they were more likely to begin with lower case s.

ReplyDeleteThat make sense? Here's an example:

Let's say it is 1640 and we want to write "surprises." Most likely what you'd see is "fuprifes." Let's say it's 1785. Then you'd probably see "suprifes." If it is 1800, then you'll probably see "surprises," just like we'd print it today.

Why did it change? Probably because it was confusing. Why was it like this in the first place? I think it's modeled on the Greek, which also has two forms for the letter sigma (the equivalent of s). By analogy, Hebrew has five letters with a double form, depending on if the letter is used in a word or at the end. Arabic has three forms for *all* the letters, depending on if it's used in the beginning, middle or end of a word. So the long s was quirky, but not too bad. It just faded away.

See these posts

http://onthemainline.blogspot.com/2006/03/long-s-and-short-of-it.html

http://onthemainline.blogspot.com/2009/07/quiet-demie-of-long-s.html

and don't forget to look at the Declaration of Independence which was after all printed in 1776

http://www.thefreemanonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/declaration-of-independence.jpg

Jesse, haven't read them, but I've heard of them.

ReplyDeleteIn the beginning of Children of the Ghetto by Zangwill Dutch Sam beats up some guys hassling a Jewish pedlar who happened to be his father-in-law. When the men realize who beat them, they feel honored.

http://books.google.com/books?id=320RAAAAYAAJ

pp. 12-14 or so

This is interesting. It might shed some light on Charles Dickens' possible anti-Semitism. Oliver Twist, with its Fagin character and constant references to Fagin as "the Jew", comes off as classic anti-Semitism. I was surprised to learn that when various people complained about it, Dickens said he was surprised that people were offended, and that he was not an anti-Semite (and later made a Jew the hero of another novel). I thought Dickens was faking it, or covering his rear end, or was deluded. But seeing this post, is it possible that Dickens was describing and disparaging a particular underclass type that, in his place and time (a generation after 1809) was found in Jews, while not hating Jews in general?

ReplyDeleteIntressante. Must disagree with the implied moral equivalence implied by this line, though: It doesn't take a whole lot of imagination to superimpose this image onto contemporary groups whom people associate with crime and are afraid of.

ReplyDeleteRegarding Mendoza's literary abilities, it is worth noting that he published an autobiography in 1826, excerpted in Schwarz, Memoirs of my People.

ReplyDeleteEH