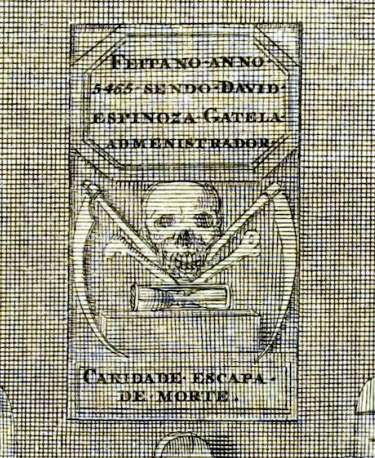

An eagle-eyed reader pointed out to me that one of Bernard Picart's engravings in Jean Frederic Bernard's massive Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde (1723) features the following wall hanging (in a shul ? funeral parlor? the home of the deceased?) in Amsterdam:

The Portuguese sign reads:

Feitano Anno

5465 Sendo David

Espinoza Gatela

Admenistrador

and below the skull is

Caridade Escapa

De Morte

The inscription means "Made in the year 5465 (1705), being David Espinoza Gatela Admenistrador" (readers, help please?).

Incidentally, Espinoza is the same name as Spinoza, the former being how a Spanish or other Iberian language speaker must pronounce a word with an initial consonant cluster, (I think it's called a word-initial epenthesis), analogous to the aleph prostheticum, or prosthetic aleph, in Hebrew and Aramaic, in which certain words require adding an aleph to the beginning for ease of pronunciation. One famous example is, probably, the name Ahaseurus, as well as other Persian names in the Bible, which lacked the initial consonant in the original language. Of course here the opposite is the case: Spanish required Espinoza, but that is the real name - but other European languages did not require it, so it became Spinoza.

Below the spooky skull is Caridade Escapa De Morte, which is of course, צדקה תציל ממות!

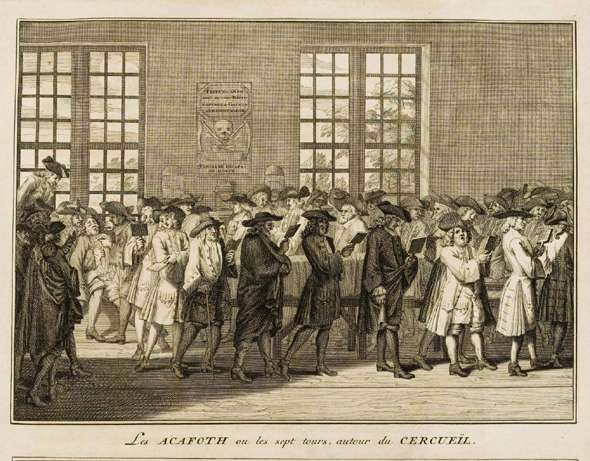

The complete image below is small so that it fits here, but please click it for much greater detail. The details of the dress, expressions, etc. are not to be missed!

The French caption is Les Acafoth ou les sept tours, autour Cercueïl, which means The הקפות (using the Western Sephardic transliteration, Acafoth), or seven circuits around the coffin.

Also note the horn book style tablets they're holding for more easily reading whichever prayer it is that they read while engaged in this funerary custom, which is describe in the 1733 English translation as follows:

"After the coffin is nailed down, ten chosen Persons of the most considerable Relations and Friends of the Deceased turn seven Times round the Coffin, and all the Time offer up their Prayers to God for his departed Soul. This is the Practice in Holland, where the Design of the Plate which represents this Ceremony was drawn from the Life."

A big thank you to Mordechai Ovits for solving a technical problem for me, namely grabbing images from a tricky flash viewer (extremely high resolution ones at that).

I think I may have solved the mystery of the inscription. On Google I found that a copy of this engraving is available on eBay for $200. A "rough translation" provided in the item description guesses that the scene was "in the home of David Espinoza Gatela," which supported my guess that Gatela was part of the name. But it seems more likely to me that the plaque marks the construction or dedication of a funeral home (I wouldn't have guessed that they had such things back then) that was "made" in 1705 when David Espinoza Gatela was the administrator -- of the home or of the entity that built it.

ReplyDeleteYou mean this.

ReplyDeleteWow Dan, you are good. You're right, it is probably the full name.

What's with the long hair? Is that what they did in Amsterdam?

ReplyDeleteYes, it's what they did. Some of them are probably wigs, but not all of it.

ReplyDeleteBut not only Amsterdam. There's a nice picture of R. David Sinzheim, author of the Yad David, head of Napoleon's Sanhedrim, highly praised by the Chasam Sofer, where you can not only see that he clearly had long(ish) hair, but he even has a very nicely stylish curl in the side not unlike George Washington. (This is NOT the famous picture of R. Sintzheim you might see by searching Google Images.) This would be the early 19th century in Alsace.

I plan to post the famous panel paintings of the Prague Chevra Kadisha in 1772. Almost everyone has long hair. I once posted a portrait of the Chasam Sofer painted in 1811 where he appears to have relatively long hair. However it should be pointed out that the Chasam Sofer himself criticized people who grow long "tchups" (like the gentiles) in a derashah from 1833 (pg 27). However, this isn't so difficult, because in the portrait he didn't have one. He was talking about stylish, 19th century gentile hair. In addition, this was more than 20 years later. Things change. By the 1960s squares were getting all upset at the long haired hippies, while people were still alive who remembered when wearing long hair (and beards) was still an acceptable, mainstream practice (late 19th century). In other words, it's the attitude, not the style. (Recognizing possible halachic problems with a בלורית, but it doesn't seem like he's talking about that.)

In fact one of my early "Huhs?" was the fact that in almost all historical depictions of Jews before, but even into early modern times they are seen wearing their hair long or longer than we are accustomed today.

That is truly cool. Definitely not very chassidish.

ReplyDeleteFunny thing to say on a headstone or wall hanging that "charity saves from death." Does this imply that the deceased was miserly? To my lights, it's an exhortation best expressed among the living, at a Rosh Hashana or Yom Kippur service . . . but maybe a little tacky to repeat or display in the presence of corpse.

ReplyDeleteI think it's taken as eternal life, ie, life after death. Everyone dies, so obviously tzedakah does not save from death (even though the Gemara gives illustrations where it did save from a literal death, such as the story of Rabbi Akiva's daughter who fed a poor man on her wedding day, and then stuck a pin from her clothing into a wall. Later is was revealed to have impaled a snake that could have struck her).

ReplyDeleteAlso, if the skull imagery was a reminder of mortality than the exhortation could be a way of sweetening it.

[From my notes to Mishlei 11:4, where the "charity saves from death" verse appears. A little drushy, but why not - DF]

ReplyDelete11:4 – לֹא-יוֹעִיל הוֹן, בְּיוֹם עֶבְרָה; וּצְדָקָה, תַּצִּיל מִמָּוֶת

Possibly the idea here is based upon the elementary notion of middah kinegged midah - God pays back measure for measure. Thus, since the Talmud in Nedarim describes a poor person as dead, giving him charity can therefore be seen as reviving the dead. In reward for this resuscitation, therefore, charity saves also from death.

My guess is that the "funeral home" was provided for poor folks who couldn't afford to have a funeral elsewhere, hence the reference to "tzedakah," not as a swipe against any individual deceased person, but as a motto of the group that sponsored the facility -- and maybe as a sort of continuing "appeal" for more donations.

ReplyDeleteGreat guess, but actually I found out what's going on. I'm doing another post on it, but let's just say for now that the building depicted is still around and even has a web site.

ReplyDeletebut maybe a little tacky to repeat or display in the presence of corpse.

ReplyDeleteTacky perhaps, but at a funeral yesterday I counted no less than six people collecting money for charity while chanting "tzedaka tatzil mimoves".