Dr. Nancy Sinkoff describes the circumstances behind the French essay on pg. xiv of her 1996 dissertation Tradition and Transition: Mendel Lefin of Satanow and the Beginnings of the Jewish Englightenment in Eastern Europe, 1749-1826:

Written for the National Education Commission of the last autonomous Polish parliament, it outlined the creation of a state-appointed rabbinate, the obligatory study of Polish in Jewish schools and proposed the occupational restructuring, or "productivization," of the Jewish community of Poland.

Sinkoff writes further (pg. 73) that Lefin explained later, in an unpublished manuscript, that his pamphlet was written as a response to Hugo Kołłątaj's order (and the NEC's agreement) that all Jewish men should shave their beards. A translation of this order that Sinkoff quotes is "All the Jews living or domiciled in the States of the Republic, with no exception, must shave off their beards and stop wearing the Jewish dress; they should dress as the Christians in the States of the Republic do." While agreeing in principle for the need for reform, Lefin's belief was that non-Jewish would-be reformers of the Jews could not be successful because no matter their good intentions, they do not really know what is good for the Jews. In the essay he quoted Montesquieu's condemnation of Czar Peter I's order forcing Muscovites to shorten their beards and clothing (to modernize them). Lefin believed the analogy was obvious; such an order was despotic.

Lefin intended to not only remain anonymous, but also that the identity of the author as a Jew should not be apparent. For this reason he also wrote in the most 'objective' manner possible, even quoting from antisemites like Voltaire, with the hopeful result that the Polish Parliament would not realize that the essay they were debating was written by a Jew. In the manuscript referred to above, he writes that he adopted this method based on a Talmudic story in Meilah 17a:

Interestingly, as the essay was published anonymously, for the reason outlined above, one wonders how it is that the identity of the author was already known in 1792, when the review (translated into English from a German paper) appeared.שפעם אחת גזרה המלכות גזרה שלא ישמרו את השבת ושלא ימולו את בניהם ושיבעלו את נדות הלך רבי ראובן בן איסטרובלי וסיפר קומי והלך וישב עמהם אמר להם מי שיש לו אויב יעני או יעשיר אמרו לו יעני אמר להם אם כן לא יעשו מלאכה בשבת כדי שיענו אמרו טבית אמר ליבטל ובטלוה חזר ואמר להם מי שיש לו אויב יכחיש או יבריא אמרו לו יכחיש אמר להם אם כן ימולו בניהם לשמונה ימים ויכחישו אמרו טבית אמר ובטלוה חזר ואמר להם מי שיש לו אויב ירבה או יתמעט אמרו לו יתמעט אם כן לא יבעלו נדות אמרו טבית אמר ובטלוה הכירו בו שהוא יהודי החזירום אמרו מי ילך ויבטל הגזרות וגו'יFor the Government had once issued a decree that [Jews] might not keep the Sabbath, circumcise their children, and that they should have intercourse with menstruant women. Thereupon R. Reuben son of Istroboli cut his hair in the Roman fashion, and went and sat among them. He said to them: If a man has an enemy, what does he wish him, to be poor or rich? They said: That he be poor. He said to them: If so, let them do no work on the Sabbath so that they grow poor. They said: ‘He speaketh rightly’, let this decree be annulled. It was indeed annulled. Then he continued: If one has an enemy, what does he wish him, to be weak or healthy? They answered: Weak. He said to them: Then let their children be circumcised at the age of eight days and they will be weak. They said: ‘He speaketh rightly’, and it was annulled. Finally he said to them: If one has an enemy, what does he wish him, to multiply or to decrease? They said to him: That he decreases. If so, let them have no intercourse with menstruant women. They said: ‘He speaketh rightly’, and it was annulled. Later they came to know that he was a Jew, and [the decrees] were re instituted. [The Jews] then conferred as to who should go [to Rome] to work for the annulment of the decrees. . .

Since his pamphlet is sharply critical of Chassidism (and it's interesting to see even a small blurb about it in English in the 18th century, as we see above) I thought it might be worthwhile to post some 18th century drawings of Polish Jews and non-Jews, in light of the oft-repeated contention that 19th century Chassidic dress (and by extension contemporary) is actually the form of dress worn by the Polish nobility two or three hundred years ago. Keeping in mind that this is only partial evidence so it can't settle the case either way, you be the judge:

Polish Jewish woman, 1766:

Polish Jewish man, 1768:

The king of Poland, 1700:

Queen, 1700:

A Polish merchant:

A Polish noblewoman:

These images were taken from a four-volume work called A collection of the dresses of different nations, antient and modern (London, 1757-72). The artists were French, the work originally written in that language.

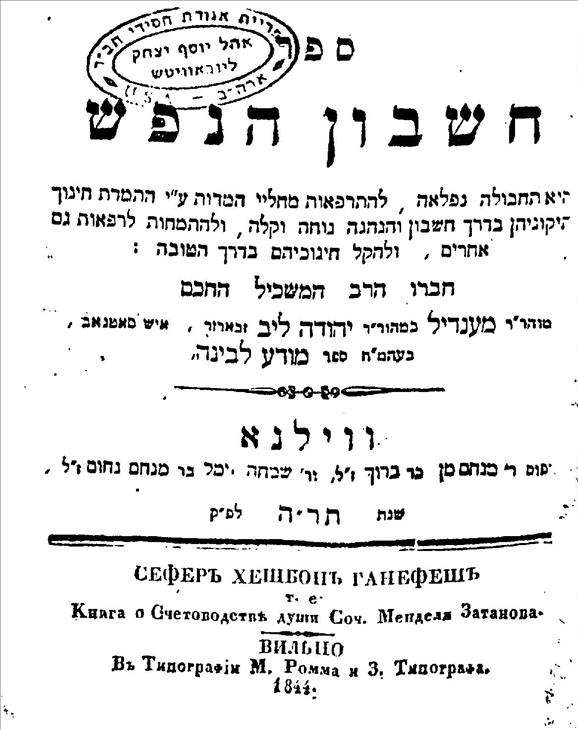

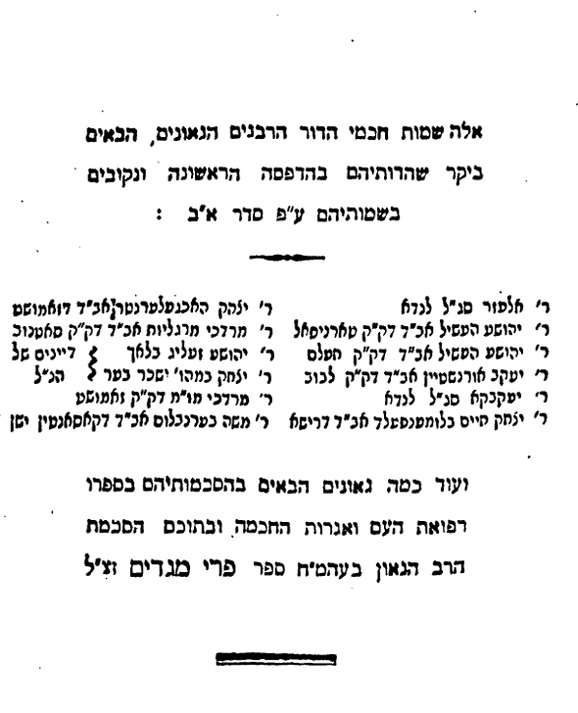

Pages from the 1844 edition of חשבון הנפש:

Exactly. So you see the nobleman wore white socks, precisely the way chassidim do today.

ReplyDeleteDF

Dress of polish nobiltiy in 17th century, NB No. 3 and 4

ReplyDeletehttp://www.biocrawler.com/w/images/f/fd/Ubior_Szlachty.jpg

http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/polish_costume_polski_ubior.htm

Nothing to do with chassidim. This became the Jewish dress:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/01/PolishJewish_Dress.jpg

http://www.lawbookexchange.com/images/51938.JPG

Chassidish fellow:

http://www.friends-partners.org/partners/beyond-the-pale/images/19-4.jpg

Great links and pictures, thanks.

ReplyDeleteThe way I see it as that there are two versions of the Chasidic-dress-is-the-dress-of-Polish-nobility-300-years-ago trope.

One is the vulgar version, which can be handily dismissed, that pretty much imagines that to look at a Chassid walking down Lee Avenue on Shabbos is to see a Polish nobleman circa 1700. Maybe the more historically conscious of those holding this view realize that the nobleman would wear a sword, and maybe some jewels, and he wouldn't have peyos. But in essence, that's the vulgar view.

The other is more nuanced, and realizes full well that Chassidic dress cannot possibly be the archaic dress of Polish nobility, but that elements of it are derived from it, much the way let us say the fedora hat is a relic of a certain kind of street dress common in America and parts of Europe 60 years ago. This view doesn't imagine that to see today's Chassid is to see a guy in a 300 year old costume, but that elements of it, such as the breeches and white socks, are definitely archaic.

The question really is, is there a connection to the dress of nobility? I would guess that most people who hold either version of this view have absolutely no idea how the Polish nobility dressed, or even how Chassidim dressed in various times.

I'm assuming you're being sarcastic by writing that nos. 3 & 4 have nothing to do with the Jewish dress? I will also say that traditional Jewish dress in Europe seems to have followed a pattern in being somewhat archaic. For example, the barrette hat worn on shabbos in Germany in the 18th century is essentially a version of a popular hat worn by the scholarly class in Europe in the 16th century. I recently posted about how in early 19th century Prague, the more traditionalist Jews persisted in wearing tricorne hats, while the more modern traditionalists began wearing top hats. And there is the famous example of present-day yeshiva Orthodox Jews who wear versions of fedoras.

All in all, I think it makes some sense that elements of the Jewish dress tended to be derived from the 'better' classes, as those were surely more appealing models. In addition, in certain times and places many Jews were, you know, wealthy, and they obviously dressed in finer fashion than the peasant class. This in turn could have influenced the group still further.

"I'm assuming you're being sarcastic by writing that nos. 3 & 4 have nothing to do with the Jewish dress?"

ReplyDeleteLet me expalain: I said "Nothing to do with chassidim" as a group, but were common to ALL Jews. Chassidim used to wear white begadim, later they returned to the boring black.

Here is the twist: nobily used silk for it's beauty, Chasidim for religious reasons (it's shatnez free - beside beauty, of course).

Okay, I got it.

ReplyDeleteI would again apply my two types, the vulgar and more nuanced views. The more nuanced sees Chassidic dress as probably being more archaic for longer, reflecting their valuing maintaining outward signs of Jewish uniqueness, rather than them initially having had some radically different Jewish dress. Did regular Chasidim really wear all white? During the week, too?

I agree with you conclusions. Just to summarize my impressions:

ReplyDelete"jewish dress" (i.a. medieval barrette, kapote, shteiml, frock, top hat, homburg, fedra etc etc):

1. Was copied from the dress of the upper class (not the peasants).

2. It entered the Jewish world decades after appearing in the secular world.

3. It was used by the Jews decades and centuries after dying out outside.

Many times a particular costume gets a specific function: synagogue dress, bigdei shabbos, rabbinical dress etc. etc.

http://www.geschichteinchronologie.ch/MA/judentum-fleck-u-hut-d/004-frz-judenfleck-judenhut-u-judenkleidung.jpg

Basically, except I'm not so sure that these fashions always enter decades behind the outside world. For example, the fedora seems to have gained traction at the same time as it was introduced in the outside world. Maybe this was not the pattern of a few hundred years ago, but I'm not so sure about that.

ReplyDeleteOh, here is one of my favorites. Germany, early 19th century. Everybody has an archaic synagogal dress, except the "frei" guy in the front who is wearing a frock...

ReplyDeletehttp://static.newworldencyclopedia.org/3/37/Der_Samstug_%28Saturday%29.jpg