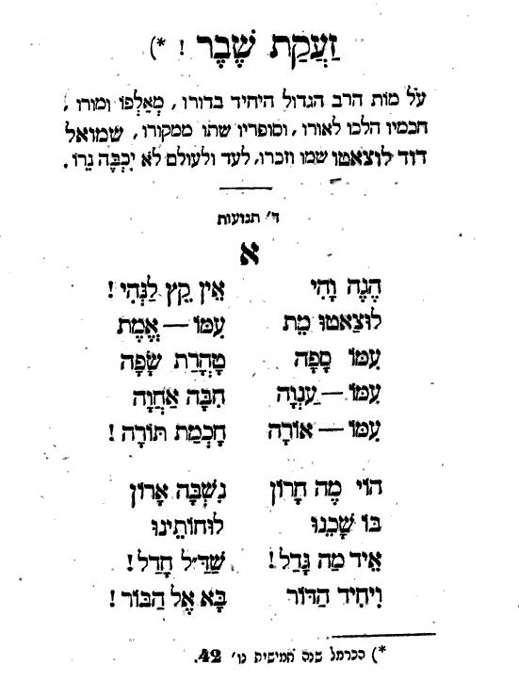

It was originally published in Hamaggid 11-15-1865 pg 349. If you're the sort of person who likes to see it in the original, you can click below to enlarge:

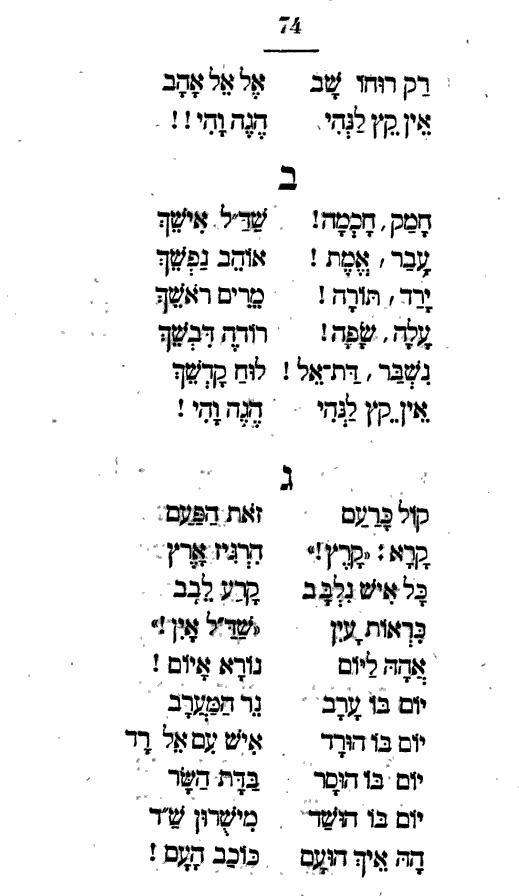

Adam Ha-kohen is depicted below, bottom left:

Interestingly, here is a mention of Adam Ha-kohen on the Yated web site:

Once, somebody came to Rav Simcha Zissel on erev Shabbos when it was almost Shabbos, to give him a piece of good news, namely that Adam Hacohen, yemach shemo, the leader of the maskilim had died.What's amazing about this piece is that the author, a famous maggid, appears to me to miss and undermine the mussar message he was trying to bring out! It's one thing to say that the Chofetz Chaim used it because he felt it was appropriate given his personal experience. It's another thing to use the phrase yourself even as you mention that the great ba'al mussar R. Simcha Zissel felt that the proper attitude toward him after his death was pity. Can that be squared with an epithet like yemach shemo?

(I apply the wish yemach shemo to that rosho because the Chofetz Chaim also did, explaining that he didn't use the phrase about any Jew, with the sole exception of Adam Hacohen who destroyed and ruined many Jews. The Chofetz Chaim related that the maskilim used to search for gifted individuals, whom they would send to university in Berlin. He said that when he was fifteen, they tried to lead him off the right path R'l, but that boruch Hashem, was saved from them. That was the reason that he said yemach shemo.)

On that Shabbos, following the news that Adam Hacohen had died, HaRav Simcha Zissel's face wore its usual pale complexion, as he said, "Now he sees the truth, how he deserves to be pitied . . . " Rav Simcha Zissel was exemplary in the trait of sharing others' burdens with them. Thus, after the man had died and was no longer able to ruin others, he exclaimed that he deserved pity.

link.

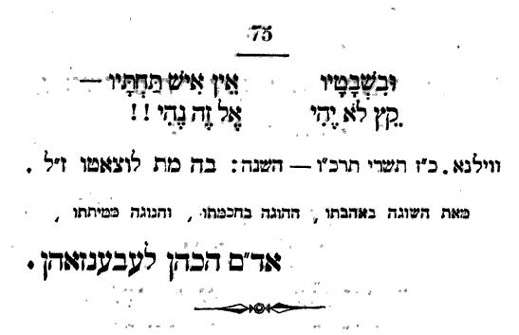

In any case, this is a well known piece of Lithuanian yeshiva lore. Another Yated article mentions it along with the evident source. Below is the discussion about it in Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky's Making of a Godol, which is worth reproducing even though it basically comes from the same source (pp. 264-65; however I combined it into one image):

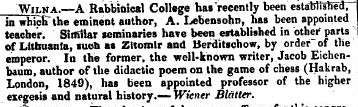

I'm a firm believer that history is best illustrated not only by quotes from primary sources, but whenever possible to see the sources themselves. In this role there's nothing quite like newspaper and periodical articles to awaken the awareness that history was once current events. For me and many readers, this is best seen in English, where another layer of foreignness, and hence remoteness, is removed. Below is a news blurb in the October 4, 1850 edition of the Jewish Chronicle:

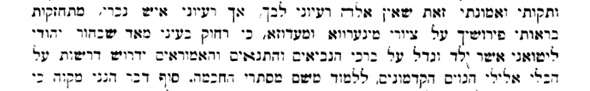

Also of interest, see Iggerot Shadal Vol. 2 pg. 1093:

Here, in a letter dated 10-2-1850, Shadal chides Adam Ha-kohen's son Michael (also known as Micha) Yoseph Lebensohn, who is considered by many to have excelled his father as a Hebrew poet (he's also depicted above, upper left). He would send Shadal his poems for judgment and criticism, and he would respond. Here Shadal is chiding him for his references in his poem קֹהֶלֶת to Minerva and Medusa. It's very hard for him to understand, writes Shadal, how a Jewish Lithuanian bochur reared on a diet of the Prophets, the Tannaim and the Amoraim could be inspired to write poetry by the Greek gods of old.

The issue of classical imagery in Jewish literature is a very interesting one, and deserves a post some time. There is one very notable example, of a great posek whose poetry included such imagery. Suffice it to say, while it was perfectly consistent for Shadal to be dismayed by Hebrew poetry inspired by Greek thought, such imagery was far from absent in Italian Hebrew poetry. But Italian Jewish culture was Italian Jewish culture. Here Shadal appears to be particularly dismayed to see such an incursion into Lithuanian Jewish culture. What's a Litvak bochur doing writing about Medusa?

To me, the mussar lesson is not that one of the greatest of the maskilim felt this way, but that despite having such a sharp disagreement and criticism of the very approach the young man had taken, he still loved him, wanted to dialog with him and be a positive influence on him.

Seems from MOAG that the Yeshiba was known as Radin, not Chafetz Chaim in the 20's?

ReplyDeleteIs this comment meant for the other post, with the receipt?

ReplyDeleteI don't really see it as a contradiction.

The Yated's version makes it seem like these people were kidnapped into the Russian army. It definitely wasn't a positive thing, but c'mon.

ReplyDeleteAs an aside, Igros Shadal was published by Isaac Graber, a cousin to my grandfather whose name was also Isaac Graber.

Haha. For them, it was the same thing, or worse. In terms of it being a positive thing, it all depends on one's perspective. From my perspective, Adam Hakohen wasn't bad at all. On the other hand, it's almost certain that had young Yisrael Meirl become a Hebrew poet he'd have never written the Mishnah Berurah. And where would we be then?

ReplyDeleteInteresting about your cousin (do you mind emailing me? As you're anon, I'd like to know more). I haven't been able to find a whole lot info about Shealtiel Eisig Graeber. (Was your grandfather Shealtiel Yitzchak, too?)

A combination of the 2 posts. In this post, the excerpt from MOAG speaks of "a Radin talmid" not a CC talmid.

ReplyDeleteMany yeshivos were known by the town they were in, even thought they also had an official name. Also, MOAG's own text is not testimony about the 1920s such that you can parse a term in it in R. Kamenetzky's own word. It was written in the 1990s! ;-)

ReplyDeleteOn the subject of poetry, its intressante. Haskalah is as alive today as it was in the 19th century, maybe more so. But you know what's completely gone? Poetry. We have blogs dedicated to seforim and to biblical criticsim and to talmudic criticism and to excessive chumrahs - all the same tropes they talked about in the good old days. But I sure dont see a lot of blogs dedicated to poetry.

ReplyDeleteAs a tentative theory, so that I can get credit for it when someone decides to write a paper on this phenomena [cite me as "DF", they know who I am] I suggest the following:

1) We Jews are simply mimicing the general disappearance of poetry in society. Now, as to why THAT is happening, I think it has to do with the watering down of standards. When garbage writers like Alan Ginsberg or Maya Angelou are considered "poets", it makes people capable of real poetry decide to focus their efforts elsewhere. So gone are the Frosts and even the Sandburgs. And, consequently, gone are the Bialiks and the Hakohens.

2) We are a more cynical generation, and cynical men dont write poetry.

3) Alternatively, our maskillim dont know Hebrew quite well enough. [I have my doubts as to this postulate. But I think the first postulate is emes l-amito shel torah, and maybe the second is true, too.]

DF

I suspect that that's partly why the official line is scorn, that Haskalah is really dead, that the old one were at least talented, even if they were horribly krum, etc. The second part of it is Israel. Hebrew expertise can't have the mystique it had 150 years ago, when half the world's Jews think in Hebrew, even if obviously most of them aren't talented or original writers in the language.

ReplyDeleteBut your reasons may becorrect too. Poetry is still alive, but is not as prestigious a genre of literature (or so it seems). Interestingly, Shadal considered "knowing a language" to mean "can compose poetry in that language," and by that standard he considered himself to know, besides obviously Hebrew and Italian, French, German, Latin, Aramaic and Syriac. However he did not "know Arabic" because he didn't consider himself competent to write verse in Arabic. I'm not clear if he knew English, in the regular sense of the term. In one of his youthful letters he cites an English book, but it may have been available in French. But clearly he couldn't write English verse. Thought and spoken like a man born in 1800.

Re your point about Ginsberg et al. Obviously that's personal opinion. Poetry needs to evolve just like music and art. People can't very well keep plugging away in the exact same form century after century. I suspect that because of the completely twisted relationship we have with Hebrew, ie, somehow demanding grammatical perfection, people just don't feel like writing regular Hebrew verse according to the rules is really artistic. Finally, of course there is plenty of Hebrew poetry. It's just not a favored past time of yeshivaleit.

Good point about the proliferation of Herew detracting from the mystique of writing poetry in Hebrew.

ReplyDeleteAnother reason yeshiva students dont write it, perhaps, is because they're simply not as talented. Back then the best and the brightest (with exceptions) went to yeshivah, not any more today.

Which English book are you referring to? I remember he cites Blondel in the letter about Jacob's sheep.

DF

See R. Yosef Mashash's lament about the precipitous recent decline of (Sephardic) Jewish poetry, in his פרשת תולדות השיר, in his נר מצוה

ReplyDeleteובכל דור ודור צצו ופרחו משוררים חדשים עד הדור הזה ועד בכלל. ואך זה כשני דורות ועוד. ירדה החכמה הזאת פלאים אצל המשוררים הספרדים. כי נמצאו שיריהם משוללים מהחן והיופי ומכל רעיון. זולת איזה שירים מעטים ונער יכתבם. אשר ריח השיר מרחפת עליהם.

ואך בדור הזה ירדה עוד פלאי פלאים ...

http://hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=7558&pgnum=136

In Shadal's comment on Gen. 30:39, he refers at length to Blondel's book "in English" concerning the so-called "power of suggestion" and Jacob's sheep. James Augustus Blondel was a French-born physician living in England. The book that Shadal referred to was probably one that Blondel wrote in 1729, which was translated into French and other languages. Because Shadal so rarely makes mention of English sources, my guess is that in this case he saw the French translation.

ReplyDeleteIn addition to the reasons cited above for the decline of Hebrew poetry, can anyone name a day school or yeshiva that actually teaches its students to write poems in Hebrew? Most graduates of such schools can barely string a Hebrew sentence together, never mind composing verse.