In England it was believed by many that the English tongue had reached a stage of sufficient maturation and magnificence that it now needed to be protected, for its fate would be degradation without some way of fixing it in place. While we now know that this is essentially impossible to do with a dynamic language, at that time, the scientific method was ascending and the necessity of defining and fixing all sorts of things was agreed. Exactly how long was a yard? What exactly is the color red? All those questions and more were being considered and the move was in the direction of precision. So although one might think Jonathan Swift stuffy for objecting to the contraction "couldn't" (*gasp*), few among us would think the idea of a uniform orthography (spelling) is stuffy. In fact, most people can't really understand how there could not have been one. Bear in mind also that at the time the flux and ferment in English was far more extensive, and more importantly, visible than it is for us.

This would mean, at the very least, the assembly of a lexicon or word list. Several modest attempts were made in this direction, such as Henry Cockeram's The English Dictionarie: or, an Interpreter of hard English Words (1623). By the eighteenth century English dictionaries were being produced with many tens of thousands of words. Naturally the most celebrated achievement in that century was Samuel Johnson's, but the march towards better dictionaries continued unabated before and since.

To backtrack before Johnson, one such dictionary of English was compiled by Nathan Bailey, whose Dictionarium Britannicum Or, A Compleat Etymological English Dictionary Being Also An Interpeter of Hard and Technical Words (1721) was a monumental work which served as the bedrock for Johnson's.

In it there are some interesting supposed Hebrew etymologies for English words. Some of them are fanciful and some are, of course, derived from Hebrew. Here are some:

1.

The root here, אבך, is meant in the sense of וַיִּתְאַבְּכוּ in Isa. 9:17 (to roll up, " they roll upward in thick clouds of smoke.") OED knows nothing about it.

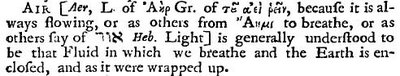

2.

In modern Hebrew, אויר avir, certainly sounds a lot like air! Is אויר derived from ו?אור

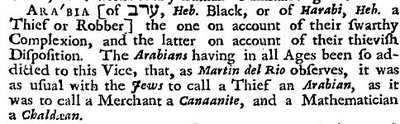

3.

No comment.

Okay, one comment: I've seen some speculation that ערב is the same root as עבר with some natural letter transposition. In other words, think of Arabs as Herbews. Maybe.

4.

This word seemed interesting in its own right. Before the OED (Oxford English Dictionary) no serious attempt to catlogue every word in the English language was made. The task was too herculean to contemplate (see Simon Winchester's The Meaning of Everything for the ingenious solution the OED used to achieve the feat it did; which even then did not literally catalogue every word, and besides took almost 70 years to do it) . Bailey's dictionary, as others, were generally one-man attempts to catalogue as much as one could. Since they were not exhaustive, the words chosen do reveal some window into the worldview of the lexicographer as well as in some sense into the culture of the time. Words like this are included, as well as many, many other biblical allusions, Hebrew weights, ancient Near Eastern gods etc.

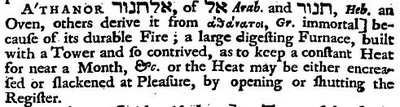

5.

This word is pretty archaic, but according to the OED an athanor is "a digesting furnace used by the alchemists[...]" and made its way into English through Arabic (hence the "a-" prefix) but a tannur תנור should be pretty recognizable to anyone who learns Talmud, or a six year old who learns Mishna (e.g, Akhnai's Oven (תנורו של עכנאי).

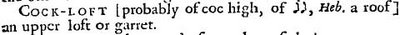

6.

Fun archaic word. I doubt that "cock-loft" is from גג. Call me a cynic.

7.

This one is a bit predictable, and interesting also because as far as I can tell a ד should be able to switch to a צ (shouldn't it?). But, alas, the English word "earth" didn't form fully from a Hebrew womb, but comes from a common Old German word. Biblical influences on English are very plausible. Biblical influences on ancient Teutons are less so. Edenics aren't my cup of ch'a.

8.

This one was chiefly interesting to me because I learned that the word comes from the coin it cost to read the newspaper. It would be as if many newspapers were called dimes or whatever they originally cost. The Daily Dime sounds nice.

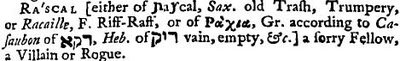

9.

I think this etymology is a Bailey original. OED and the Online Etymology Dictionary basically have no clue where this one comes from, except that it shows up around 1300. Hebraism in England had already begun by that date, so I leave open the window about a millimeter on this one. If no one knows, then who knows?

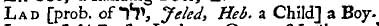

10.

One of the many words which are English but are actually Hebrew, thanks to the Bible. Of interest is that its meaning reflects some of the debates in biblical scholarship of the day.

11.

Outsider perception is always interesting.

12.

This reflects the debate which raged for a couple of centuries on the origin and authority of the nekkudot (see here and here). Bailey seems to favor the view that they were originated by Ezra (and in so doing indicates his more traditionalist bent), but is gracious enough to mention the other view.

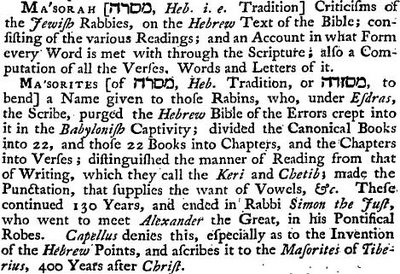

13.

I have no idea if there is any relationship between the Greek and Semitic סתר, but I suppose its possible. After all, those two regions were only a sea away, and the two language groups did influence each other.

14.

This one is great!

To clarify, Nisan is the first month of the Jewish calendar and correlates, roughly, with April. However, the Jewish New Year is in the seventh month, Tishrei (don't ask! ;) ). Presumably Bailey knew that Nisan is the first month and knew of Rosh Hashanah in the seventh month. As there is no entry for Tishrei, he must have figured that Nisan is the seventh month in which the New Year occurs.

15.

Fanciful, but fun.

16.

This one is really something. I think there are parallels for such etymologies in rabbinic literature, although I can't offer an example at the moment.

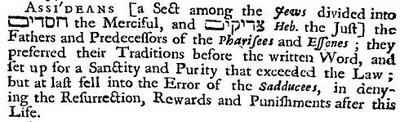

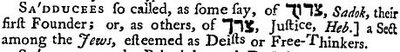

17.

Sign of the times. Deism and free-thinking enjoyed a particularly good reputation in the 18th century, thus projecting themselves onto the ancient Sadducees.

No comments:

Post a Comment