Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Making of a[n] myth urban legend

URL is jewishstudent.blogspot.com, but I'm not sure which the baalat ha-blog wants to be known by.

Thursday, February 23, 2006

Was George Washington perfect?

Years later, Whitney [a Lincoln legal colleague from 1850s] recalled a lengthy discussion about George Washington. The question for debate was whether the first president was perfect, or whether, being human, was fallible. According to Whitney, Lincoln thought there was merit in retaining the notion of a Washington without blemish that they had all been taught as children. "It makes human nature better to believe that one human being was perfect," Lincoln argued, "that human perfection is possible."From Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin, via Lamed.

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Monday, February 20, 2006

Don't forget to see the forest too

It was at the behest of a rabbi I study with that I went and visited the Lakewood Yeshiva. I had never been to a yeshiva before in my life and I sort of did this out of some degree of curiosity but more out of a sense of moral support for what had been such a central part of this rabbi’s life but I have to tell you when I got there I was absolutely knocked out by it. I will tell you that it was the single most intellectually active, energetic, fascinating environment I had ever witnessed. There was a sort of buzz and just sheer concentration and joy in the learning process and it was literally visible to somebody like myself.

I mean, I said it afterwards, it made Harvard Law School, which I happen to have attended, look like a kindergarten. It was absolutely extraordinary to see so many people - from various walks of life - in there for the sheer joy of learning about their religious tradition. And the sheer intensity and intellectual demands of this place made it such a unique place to visit. So for me, it was absolutely a stunning experience and I wish everybody could have the chance not only to visit it but to have a guide like I did.

Orthodox Judaism deals with Bible criticism

Allow me to explain. With regards to higher or literary Bible criticism, there have been three or four Orthodox approaches.

Early on in the game, there were Orthodox scholars who took it on point by point. Well, maybe not scholars, but there was R. David Zvi Hoffman.

The second approach is the most widespread, which is to pretend it doesn't exist. I think in my entire yeshiva career I heard one roundabout reference to Bible criticism, which is to say that dealing with it meant ignoring it completely.

The third approach is to sort of introduce Bible criticism, either in a 45-minute lecture or in an essay, most of the time being spent summarizing the history of the theory and then maybe 10% devoted to highlighting a weakness or two, and then declaring that as a theory it is dead and has been dead for 90 years.

A fourth approach, which is unlikely to gain much in the way of adherents, is that typified by R. Mordechai Breuer, which allows that the prevalent theory, the documentary hypothesis, is correct insofar as it has identified four strands and the hand of a redactor, but nevertheless the Torah was written be-davka this way and is al pi Hashem be-yad Moshe, just as tradition holds.

The first approach has merits, but is exhausting. If there are a thousand 'problems' which led to the two types of explanations, the traditional Torah she-be'al peh and the untraditional documentary hypothesis, the former provides a thousand answers to the thousand problems while the latter essentially provides one answer to the thousand problems. That means that in order to really have a good grasp of how Tanakh 'works,' with the thousand problems (I made the number up, for argument's sake) one has to do a lot of juggling. On the other hand, a sweeping theory which basically answers the thousand problems in one sentence approaches Occam's Razor a bit more, although I suppose one could argue that "Torah she-be'al peh" is also a sweeping theory. Either way, when Bible criticism is taken on in every detail one usually ends up in quicksand.

The second approach makes some sense, insofar as we could probably make some sort of calculation. If a hundred students are not exposed to Bible criticism by the time they're 20 years old, let's say that 70% will either never be exposed to it, or will be entirely unwilling to entertain it. On the other hand, say that the same hundred students are exposed to it, say, by the age of bar/ bat mitzvah. Maybe then the numbers change signifigantly, maybe 70% wind up with skepticism or doubt. Or at least that must be the calculation made when students, such as myself, could spend almost two decades in an educational environment without any exposure to it (apart from my reading done on my own). But at the cost of never being exposed to what a yeshiva reponse to Bible criticism might be.

The third approach, that of lightly touching upon it and then declaring it dead is probably very good for the majority of people who the second approach dealt with. These classes and essays are like a caffeine jolt. Now the people can feel like they've been exposed to it, know what it is and that its nonsense and discredited. This works well for those who aren't really curious about it.

The fourth approach, accepting the findings but disputing the conclusions, is interesting. But it almost seems like permission to be a kofer with cognitive dissonance. Maybe that'll work for some people (I toy with it), but its hard to believe that one is being totally intellectually honest by drawing no new conclusions from the conglomeration of historical, textual, theological and other types of literary analyses which finds multiple sources in the Torah.

There is a fifth approach which has only been touched on and in my opinion badly needs exploiting.

In this Introduction to the Philosophy of Rav Soloveitchik by R. Ronnie Ziegler we are told

Let us take, for example, the question of biblical criticism. True, the Rav did not write a treatise on this topic because it held no great interest for him personally and because he felt that others, like Rav Chayyim Heller, had more specialized knowledge on the subject. However, he also makes a significant observation in "The Lonely Man of Faith" (p.10) which would suggest that biblical criticism does not pose as great a challenge as one initially would assume. The critics make their case for multiple authorship based on certain anomalies in the biblical text. Rav Soloveitchik points out in response that the Sages and the Rishonim were also sensitive to these textual anomalies, but they offered different explanations for these phenomena because they were working with different assumptions than the critics. In other words, taking note of textual phenomena is one thing, but interpreting the phenomena is something else entirely.This is the fifth view. Whether or not something is a cogent alternative will be judged by the reader. But even though R. Soloveitchik only went down this path for one topic, it would seem to me that rather than undetake a point-by-point refuation (first view), rather then ignoring it (second view), rather than pretending to have conquered it (third view) and rather than simply accepting it and hoping people will still believe (fourth view) scholars need to prevent alternatives, not at the local level, one 'problem'/ one solution (multiplied a thousand times). But problematic 'sugyot' in Torah and Nakh ought to be taken on, as Bereishith 1 & 2 were, and a new view put forth addressing the forest rather than the trees.

...

Furthermore, Rav Shalom Carmy points out that two approaches are possible when confronting critics:

A) One can respond to them point-by-point, but then one is playing in their arena and is constantly on the defensive.

B) One can offer a compelling alternate understanding. This is precisely what the Rav does in "The Lonely Man of Faith." Instead of undertaking a detailed critique of the critics' interpretation of the first two chapters of Bereishit, he undercuts their arguments entirely by presenting a cogent alternative. Thus, he DOES actually confront the critics - in an indirect yet constructive manner, rather than in a direct but defensive manner.

Of course a cycnic will say that this is an impossible task, because apart from the one or two areas, like the beginning of Bereishith, it cannot be done. Other cynics on the other end of the spectrum will just say "Phooey, kefira." But until it's been tried, how do we know what the correct Orthodox response to Bible criticism is?

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Neshama Carlebach's Purim concert cancelled on account of J4J

A few days ago it was brought to my attention that Neshama Carlebach was to perform at the following event:

Purim in the city...

As it turns out, if you clicked the link, the shul sponsoring the event was a Jewish Messianic congregation (Hebrew Christian, if that wasn't clear enough).

In the ad above, Neshama Carelbach's picture appeared as did the announcment of her performance. That has now been altered after she canceled, when it was brought to her attention that she had agreed to an engagement at that event.

She wrote the following to people who asked her about it:

Dear friends,Does anyone know if her late father would not have takka kept the engagement and considered it a kiruv opportunity? I am not blaming her either way, or criticizing her handling, but its an interesting question. Might one have a legitimate reason for performing at a Purim event at a J4J-type synagogue?

I was invited to sing for Congregation Beth El of Manhattan, a congregation of Messianic Jews on March 12, 2006. Naively, I had no idea what their ultimate goal and mission was when I first accepted this invitation.

Now that I have become aware of what this organization represents, I will be canceling my appearance. I absolutely believe in One G-d, and live and breathe for my own Orthodox Judaism. While I respect the ideologies and rights of all people, I feel it to be my own religious and spiritual imperative not to participate with a group that is in direct conflict with my own beliefs and way of life.

I very much feel, in the tradition and inspiration of my father, Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, that my work in this world is to spread love, light and healing through my music.

It is very painful to know that my acceptance of this invitation may have hurt or offended anyone, just as I'm sad to know that by deciding not to go forward, I may offend some of the people who worked so hard to organize this event. I hope that the reasons for my cancellation will be understood.

I appreciate the concern that you have shown, and thank you for reaching out to me.

I pray that we can continue to be strong Jews and good people, who can, with love and respect, stand up for what we believe in while never growing callous to the impact of our actions on others.

With love and apologies,

Neshama Carlebach

Google does diqduq

Google does everything. Did you know that it knows dikduk? I wanted to see who Choshuv was (now that he's here commenting) so I googled part of what he said, "many of the "Orthodox" blogs are moshvei letzim." Google asks, "Did you mean: "many of the "Orthodox" blogs are moshavi letz?"Now that is pretty funny. :D

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Original thinking in Jewish history

In the discussion the idea was raised that a many (but not all!) Jewish thinkers of long-lasting impact bucked the norms and leadership of their day, only to be vindicated by history. I wrote that:

historically the masses weren't scientists. Rabbis were--that is to say, the educated Jews were, and educated Jews were rabbis. It's a bit circular.Along those lines I wonder if traditional Judaism is the incubator for the specific factors which produce such people. Requirements: a set of rigid religious leaders to herd the masses. They'll all be relatively intolerant of those who don't toe the line, but really they're all there to produce the setting for the people who will step out of line and do big things.

In fact, the historical example feeds the daas Torah view. It is 100% true that historically Jewish leaders and intellectuals tended to be talmidei chachamim. But this isn't because talmidei chachamim inherently know astronomy or politics better than those who aren't TCs, but because only those who were educated would come to excel in those fields. And a traditional Jewish education was impossible without heavy duty immersion in Torah. That's why you have all those Jewish polymaths who excelled in Torah and Talmud and whatever else they did, and it has nothing to do with daas Torah or hafoch ba hafoch ba.

All that said, a great deal of what is credited to Jews were products of Jews who thought outside the box, outside the mainstream and in many cases who clashed outright with the leadership who didn't appreciate original thinking. The Rambam is a classic example, but so is the father of modern Jewish historiography, Azaryah de' Rossi*, and others down to the present.

Very Maimonidean, very elitist. I don't like elitism. But is it true? Or rather, was it true?

*WRT Azaryah de' Rossi it must be mentioned that his noted antagonist, the Maharal mi-Prague was, of course, an original thinker.

Monday, February 13, 2006

Hebrew alphabet reform

Anyway, an example of autocratic reform imposed on an alphabet was Stalin's initial embrace of Yiddish culture in the 1930s, as a Soviet-approved Jewish culture, minus Judaism. An entire new Yiddish orthography (spelling system) was devised, designed to make Yiddish words derived from Hebrew look as far from how it was written in the Bible as possible. For example, the Soviet Yiddish newspaper 'Der Emes,' (the Truth) was spelled דער עמעס, instead of דער אמת. Writer Sholom Aleichem's name was spelled שאלמ אלייכעמ, instead of שלום עליכם, which is how he himself spelled his name (as you can see, this orthography did away with the סופית letters as well).

Anyway, this ניט--וורי--עמעס episode was rather short lived, as Stalin soon tired of his Yiddish Jews, closing down the Yiddish press in 1948 and shooting all the Yiddish writers in 1952.

It was brought to my attention (hat tip: Mis-nagid) about a wacky Hebrew alphabet reform proposed by Hugh J. Schonfield, author of the 1965 best seller The Pasover Plot. The Passover Plot was a controversial book which speculated that Jesus intended to fake his own death and resurrection (since death by crucifix typically took as much as 24 hours or more, the plan was to bribe the Roman soldiers to take him down after only a few hours, alive) but the plan went awry when he was speared by a soldier and so died. But I digress.

Schonfield apparently thought the Hebrew alphabet was ugly (!) and in a book called The New Hebrew Typography in the 1930s devised the following in its place (taken from The Schonfieldian Script Page):

As you can see, he created both lower-case and capital letters and the alphabet appears heavily influence by a sort of Cyrillic alphabet. I'm not sure what Schonfield's point was, but there you have it.

An example of Hebrew writing in his reformed Hebrew script (taken from the aforementioned web site):

No, no one took this seriously. Thankfully.

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Putting rabbinic stories in context

Yes, you can download it and read it, but it's an important point and it should be available for posterity on the internet, so I am posting this excerpt:

There may be some stories in this book that are known to some readers--and family members of the principals--of which the author may have a different understanding than they. For example, I was told by my son R' Yoseph that R' Shlomo Fisher told him how R' Yitzhaq Kulitz, Rav of Jerusalem, was incensed with the reaction of a "present-day rosh yeshiva" to a story he was told about how R' Isser-Zalman Meltzer was going up the steps to his house and overheard the cleaning lady singing to herself while washing the floor. R' Isser-Zalman went back down to the street and paced the ground for a long while until she had finished her work, and then he returned home. The rosh yeshiva understood R' Isser-Zalman's action as indicative of how careful he was in avoiding the sound of a singing woman (קול באשה ) for the time it would have taken him to walk from mid-staricase until entering his home--when the woman would certainly have stopped singing. "In actuality," said R' Kulitz, "R' Isser-Zalman was concerned that when he would walk into the house, the woman, who enjoyed singing while on the job, would be inconvenienced by having to stop singing for the rest of her working time." Also cf. the definitive biography of R' Isser-Zalman Meltzer, בדרך אץ החיים, where that tzaddiq's grandson records the story as it occurred--and that his grandfather himself explained his action without any reference to קול באשה; it even has R' Isser-Zalman pacing on the porch just outside the door to his house--where he could likely still hear the singing (if he chose to listen)! R' Yitzhaq Kulitz was still fuming about that rosh yeshiva's misinterpretation of R' Isser-Zalman's motive because through his wrong interpretation, he had missed out on R' Isser-Zalman's extraordinary consideration for people.

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Sanhedrin on Gemara

On the Sanhedrin.org web site, Rabbi Dov Stein writes an article called "Responsa to Daat Emet (Knowledge of Truth) Pamphlets." (The piece was translated from Hebrew by Rabbi Dr. Eliyahu Schatz.)

In the article R. Stein writes something refreshing:

This authority is given to the gemara only in the legal realm. However, this is not so with respect to opinions, and views on the existence of the world, science, legends, etc. A person can explain these items in any way, and he will not be considered as having unfit ideas.There is nothing novel about these three sentences. Indeed, they are the opinion that was expressed throughout the generations, even more than a thousand years ago. It is a reflection of a consistent tradition of ge'onim, rishonim and aharonim regarding how we can to relate to aggadah in rabbinic literature.

It's wonderful that R. Stein writes this, even in a polemical context, because it lucidly expresses that which is contradicted by the outlook of some today, of those who slammed and banned the works of R. Natan Slifkin. Given the current intellectual climate those words are indeed refreshing.

There are some more promising new ones that I've spotted recently, but I can't remember them just now. I have them bookmarked at home, so I'll add some more later.

As a separate issue, the name "J-blogosphere" stinks. It was brought to my attention* that Mormon bloggers call their circle the "Bloggernacle." Now that has style!

Let's think of something niftier, zippier and better than "J-blogosphere" and let's make it happen.

(Please don't say "Covenantal Blogosphere.")

*Hat tip: Mis-nagid.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

Jerusalem, 1903

His perceptions are quite interesting, some of which are in error (but not surprising, given that any of us would also make what are slight errors when observing an alien community). The piece is also clearly sympathetic and more than a little bit romantic.

Here is an especially interesting quote:

Many a man who appears in Jerusalem in all the garb and habits of ultra-orthodoxy has lived very differently in Europe in his younger days. Now, in the Holy Land, with the eyes of so many equally punctilious around him, he inevitably goes to extremes.Also interesting: the article is filed from "Jerusalem, Syria." Such was 1903.

Link to pdf of the article

German F. Pagan

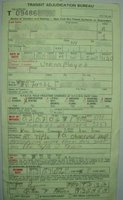

This is the ticket issued to him:

By Police Officer German Pagan. The best of all possible worlds, huh? LOL

A

On the alphabet: although I personally am more interested in the אלף-בית ('aleph-bet) than the אלפאבית (alphabet), several of the Hebrew letters are connected with individual letters of the Roman alphabet (e.g., I, J, and Y are all connected with 'Yod.') So it will be A-Z.

To begin with, as far as we can tell the ancestor of the letter א/A was something that looked roughly like the following:

Found in the so-called Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions, this symbol functioned as the consonant א in very early alphabetic writings. From there we move north to Canaan, where the letter was written in some manner of the following form:

It should be apparent that the second one is a simplified line drawing form of the former. In either case, the name 'aleph was quite appropriate, as the Semitic/ Hebrew root "'-l-ph" meant, in fact, an ox. In the Torah this form is rare, as it is more archaic, and is used in Deut. 28:4, as an example (שגר אלפיך).

In any event, this alphabet was in use in Canaan and through trade with Phoenicians (probably living in what is today Lebanon), the alphabet was acquired by Hellenes (Greeks). Initially they wrote without regard to direction, sometimes from right-to-left as in Semitic languages, sometimes from left-to-right and sometimes in both directions in the same document (which is called boustrophedon writing). Eventually the left-to-right writing prevailed, and with it came cosmetic changes to the alphabet. By simply taking a casual look at one representative of the early Semitic script one can see that it is well-suited for writing from right-to-left:

When the order reversed, so did the direction of many of the letters. So the 'aleph changed direction and came to look more like this:

In time and with subsequent modifications and inheritances (from the Greeks to the Etruscans to the Romans) we came to its present form: A

Although this post is titled "A" and not א I absolutely cannot resist showing some subsequent development of this particular letter:

The earlier three are early Phoenician and Hebrew 'alephs. The latter four are strictly developments in Aramaic, the second from right is Palmyrene Aramaic and the one all the way to the right was from Nabatean Aramaic.

One more:

This is a medieval 'aleph fairly typical of the massoretic codices. This one is from the Aleppo Codex (ca. 915 CE):

Obviously there is a great, great deal I left out in this exploration (including the cursive and Rashi scripts and my leaving the letter A to its development approximately 2000 years ago).

Future posts (B-Z) will hopefully be better, and will include traditional Jewish thought on the letters. :)

Monday, February 06, 2006

Iran's largest selling newspaper, Hamshahri, announced it would be holding a contest on cartoons of the Holocaust in response to the publishing in European papers of caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. linkGrow up.

Friday, February 03, 2006

Book Club!--"How to Read the Bible" by Marc Zvi Brettler

From Publisher's Weekly:

How does a person read the Bible, which is a product of another time and culture, and have it make sense? Brettler, who chairs the department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies at Brandeis, begins with the complicated web of doctrine, history and myth that is the Hebrew Bible and untangles it until a clear and beautifully drawn picture emerges. His mode of interpretation is the "historical-critical" method—reading the text in its historical setting, employing critical methodology to explicate and, when possible, harmonize "the multiple ancient perceptions of God, preserved in our composite Bible." After explaining his approach, Brettler takes readers through the historical periods of the Bible, placing the stories in their proper context. He explains, for example, the importance of the Jewish exile in Babylon to the people's view of the prophetic calling. He also discusses the poetic books, their formation and content, and the messages of the prophets. The result is an eye-opening journey through a familiar text, a fresh look at an old story. Written for the beginning reader as well as the scholar, this is an outstanding introduction to the Hebrew Bible and the history of Israel, and should be widely read.If there is interest, and by that I mean if even one more person "joins" then we will have a Book Club! We will discuss the book in future posts.

Note: you do not have to agree with a single word of the book or the approach it takes to participate.

"Sign up" here and stay tuned for a schedule.

edit: NPR article on the book, including lengthy excerpt from the first chapter.

Thursday, February 02, 2006

Guess who said it?

"So I say now that there are eight rhythmic modes (alhan = melodies), to each are [associated] measures of combinations of beats (tanghlm).Etc. (the full quote takes up too much space)As for the first of them, its measure is three consecutive beats (naghamat), and one quiescent.

And the second, [its measure] is three consecutive beats and one quiescent, and one moving. Those two modes stir the humor of the blood and the temperament of sovereignty and dominion.

As for the 'iqacat [rhythmical modes], which constitute the genres of [i.e. from which derive] all the rhythms, they are divided into eight modes, and they are: al-thaqll alawwal, al-thaqll al-thani, almakhuri, khafif al-thaqll, al-ramal, khaftf al-ramal, khafif al-kbafif, alhazaj.

As for the al-thaqll al-awwal, it is three consecutive beats (naqarat mutawaliyat), then a quiescent beat, then the rhythm returns as it began.

Al-thaqil al-thani is three consecutive beats, then a quiescent beat, then a moving beat, then the rhythm returns as it began.

And the third, its measure is two consecutive beats-there is not between them the tune of a beat-and one quiescent, and between putting down and raising up [and raising up] and putting down is the time of a beat. And this mode alone moves [the humor of] the yellow bile, [the temperament of] courage and audacity, and what is like them.

Who said it?

The prize: my admiration for knowing it. ;)

The Chareidi Jews of Baghdad

He learned in the Zilka beis medrash, where the chareidi Jews of Baghdad studied.Anachronism alert!

I am well aware that the term chareidi had already come into existence by 1900. But I am reasonably certain that Baghdadi Jews did not call themselves nor were they called by outsiders chareidim.

Hat tip: an email list. I don't know if the poster would want to be named, so I won't unless he or she emails me and says that I could attribute it.

B-b-b-b-banned...banned to the bone

300 in 2000 years? Even thought several more works have been banned and/ or modified or censored since 1979, somehow it seems like the most recent brouhaha (what a fun word!) began with "One People, Two Worlds," (pub. 2002). If that be the start of a recent trend then we're looking at 3 out of 300 or so--1% of the toal--in the past three-four years alone.

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

Guidelines for an Orthodox Jewish Torah translation

- Rigorously follow Masoretic conventions. Divide the text according to pesuchot and stumot divisions. Entirely ignore standard chapter divisions. Rigorously use the te'amim (trope) for parsing sentences.

- Transliterate Hebrew names and places. Forget about Moses, forget about Jacob. Every person's name should be transliterated into English characters (always using a consistent transliteration scheme). Every first instance can be asterisked: Moshe* (*Moses)

- No King James-isms. There is nothing wrong with striking passages which the King James committee translated well into English. But from the point of view of an Orthodox Jewish Torah translation, it is far better to think outside the box rather than employing recognizable terms from existing translations simply because its easy to just crib them. In other words, Cain (or, I should say, Qayin) does not rhetorically ask God if he is his "brother's keeper."

- No politics. There have been numerous instances of one or another work getting "in trouble" by critics who want the work to have done what it didn't. In the 1920s, a grandson of R. Samson Rafael Hirsch caused a stir with a literal translation of Shir Ha-shirim. Translators must resist the temptation to look over their shoulder, to render diplomatic or self-conscious translations. The only criteria must be emet, as best as possible, and there ought to be a willingness to let chips fall where they may (although deliberately seeking controversy is similarly to be avoided for the same reason).

- Be consistent. If the translation is going to be a Torah she-be'al peh translation, fine. Let it be so. Let it translate Gen. 21:21, Yishmael's wives as Fatima and Aisah (as Targum Y. does)--or let it not. The key is consistency, rather than slipshod cherry-picking through gemaras and midrashim and meforshim without rhyme or reason.

Feel free to rip mine apart and add your own.

Partly relevant link.

Critical scholarship in the olam ha-yeshiva

The surprise, for him, was that the edition was produced by a chareidi scholar and has chareidi haskamot, but cites Rs. Azaryah dei Rossi and Saul Lieberman, and is itself a critical edition of the Iggeret, written with wonderful scholarship.

It is a darn shame that this need be a surprise!

This is what the Orwellian world of certain publishing companies have wrought, the impression that the yeshiva world simply lacks critical thinking. It may be that it consciously spurns whichever modern scholarship it chooses to, but it needn't be lacking in scholarship. And even Artscroll has a mixed record. For example, in their Rashi edition a lot of important work on the meaning of the Old French words were done.

Many important works were and are written by chareidim. Every time I have been to the JTS library I have seen chareidim there to do research.

Again, the reputation of chareidi learning has suffered because of the Orwellian things we've seen over the years, bans, distortions, censorship etc. But all in all, there is no reason why a chareidi talmid chacham is incapable of comparing texts and using his kop to produce an outstanding work.

It is a shame that this isn't obvious, and is the fault of anti-intellectual elements which do exist.